Richard Hoggart discusses culture and media

BROADCAST: 1968 | DURATION: 00:44:54

Synopsis

Content Warning: This conversation includes racially and/or culturally derogatory language and/or negative depictions of Black and Indigenous people of color, women, and LGBTQI+ individuals. Rather than remove this content, we present it in the context of twentieth-century social history to acknowledge and learn from its impact and to inspire awareness and discussion. Richard Hoggart talks about the media and the cultural explosion. Hoggart explains that facts are not knowledge. There's a democratic freedom of communication with TV in America, whereas there are safeguards in place with British TV to make its viewers face reality.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

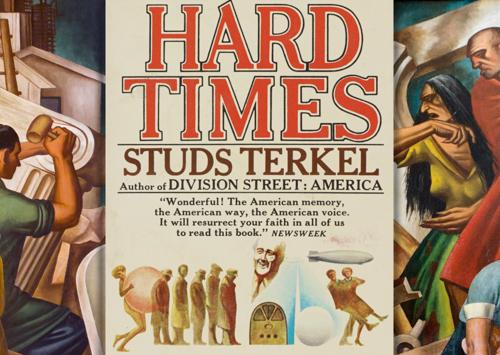

Studs Terkel Richard Hoggart wrote a book called, "Uses of Literacy" 10 years ago that perhaps has more impact today than when he wrote it. And during the latter part of the program we'll hear the voice of a night porter at the hotel where I was staying that in a way italicizes some of the comments, Richard Hoggart, and the dilemma perhaps we face today, one of the dilemmas. In a moment, the conversations after we hear from Mel Zellman and a word from our sponsors. Well, to me one of the most important books of the last 10 years was written about 10 years ago. It's called "Uses of Literacy" by Richard Hoggart, Professor Hoggart now at the University of Birmingham, I believe. This book, when I first read it some six years ago, I thought, "Wow what a -- How timely it is." And it occurs to me Professor Hoggart who is now, both of us are now visiting Penguin Books here on Vigo Street in London. This book, "Uses of Literacy" and the subtitle, "Aspects of Working-Class Life" with special reference to publications, entertainments, really deals with a gap, does it not? In this age of technology and mass communications between a great many people and those called the experts. I was curious to know since you've written this book that in a way sounds a warning. What do you think has happened during this past 10 years since publication of the book and today?

Richard Hoggart In Britain, you're thinking --

Studs Terkel In Britain, perhaps it might be a metaphor for the world.

Richard Hoggart The countries of the West, the advanced countries of the West, especially in Europe, had a society which was very largely built on the notion of hierarchies and as people became educated, and a society became more industrialized, the general notion was that everybody somehow became civilized in a kind of middle-class bourgeois European way. Now I think this has proved to be a false hope even if it was a right hope, it's a false one because as societies have become more prosperous the sense of class and status is altered in all kinds of ways. On the other hand, societies have become more commercial and a great range of new persuaders have come along to get the attention of the body of people so that what one sees today, especially in Europe, is a huge new varied entertainment culture growing up which has got very few roots in the past. I think at its worst it's about as trivial as it could be. The oddity is this, though; some of the things that have come out of England in the last 10 years in the shape of popular culture, I'm thinking of popular song or styles in dress and so on, seem to me to be much more lively and interesting and amusing than anybody could have predicted. They are I think authentic working-class creations.

Studs Terkel In a sense you're referring, of course, to using the Beatles as an example.

Richard Hoggart That would be an example, yes. You see, if if if 10 years ago you'd said now what's going to happen, what one would have predicted was that if prosperity increased, if there was more attempt to entertain and persuade masses of people, both of these things have happened, then what you would get would be a great mass of consumable entertainment just produced and processed by the market and to some extent this is true. But the surprising thing once again is the is the degree to which it's not true and the degree to which people have avoided either becoming cultivated in the middle-class bourgeois sense or becoming just mass consumers.

Studs Terkel So the one deviation from the warning you you were offering in this book 10 years ago is what might be called the revolt of the young or at least a portion of the young.

Richard Hoggart I would think that's a pretty exact summing up, yeah.

Studs Terkel You would think of this particular point. All the points you make in this remarkable book, "Uses of Literacy" where a great deal of talk of the cultural explosion, here are mass communications, here is television, and you're pointing out that something may be happening and it still is despite the revolt of the young.

Richard Hoggart Yes.

Studs Terkel You know the phrase, "Never have so many been controlled by so few."

Richard Hoggart Yeah.

Studs Terkel To paraphrase Mr. Churchill, though in a different way. This challenge is still so today, isn't it?

Richard Hoggart I think this challenge is enormous today, and it comes back to what you said at the start, they got between the controllers and the control of the people. This is true in all parts of life. I mean it's true in that there are so few producing all the television in the country. I mean that television in the States is perhaps even more than here is a highly concentrated continent-wide product producing very few varieties of material for 200 million people. This is this is staggering, it's a shame, it has all kinds of dangers. But you can surely take that much further and in a way much more importantly it's true of politics that as states become more centralized and concentrated so the gap between those who have it to do and those who to whom it is done gets wider. And I think one of the biggest single problems we've got in front of it is to make any a reality of democratic citizenship. Most of it now is a myth.

Studs Terkel Of course, also I realize also in your book you are avoiding the danger of nostalgia, you point this out, of romanticizing the past and you quote Chekhov in saying, "Yes, I've known the peasant and let's not be that romantic about the past." You point this out, too.

Richard Hoggart Yeah. And I think I don't know whether it's true in America, but here in England if especially if you're from a lower class and you've been educated out of your class there is a danger and you've been educated, say, to become a teacher or a writer in the humanities you've got two dangers and they're all thrown together. One is that the kind of tradition you're put in touch with is a very very humane and civilized tradition, very attractive tradition, it's a tradition of humane literacy over the last few centuries. The second one is that insofar as you've come from the working classes and you're being invited to join a kind of middle class int-- intelligentsia, you either join it and say nothing or you react and say, "But the people I grew up among were in all sorts of ways attractive, brave, generous." And that's a kind of nostalgia if you don't watch it.

Studs Terkel At the same time, despite the dangers, the perils of nostalgia, you do point out there was something there.

Studs Terkel You point out an oral history, an oral wit, a native wit, you point to your grandmother for an example. Well, will there be such people such as she or these minority, always a minority, of course, who you find in every class, you point out. But this kind of person, this unique person who has this, you find this among elderly Negro women, for example, in America, will their kind disappear, and if so, what or who would replace them, you see, this is an interesting question.

Richard Hoggart It's a question yes to which one can't give any firm answer. Insofar as people like your elderly elderly Negro woman and my grandmother got by staying in one place, by having roots about a foot thick and a half a mile deep. I got a sense of a kind of wisdom that was unsophisticated, not cosmopolitan but genuine, real, insofar as that depended on being in one place and having roots there'll be less likelihood of this happening; on the other hand, human beings are really resilient and you know I think they they they adapt so quickly and readily that I wouldn't be too pessimistic about it, but it will be quite hard for people like you and me with our background and generation to be able to recognize the new forms when they come. I mean we understand the older styles better.

Studs Terkel This is the point, isn't it, I'm talking now to Professor Richard Hoggart on this remarkable book, I believe it's available in America published by Penguin Books here, is a Pelican Book in England, "The Uses of Literacy", though 10 years ago, of looking through it now and again how how much it is of now, sir, despite the development of the young in the 10 years, the question of mass culture, you know, good and bad, you know, we see -- Millions can see Mona Lisa for 30 seconds as they pass by. Is this it? Is this it? You see?

Richard Hoggart I don't think we face the question of mass culture really adequately. There's a debate about it all the time, but it seems to me not a good debate neither in Britain nor in the States, and some of the American critics of this kind of thing and analysts, and especially Chicago people, have been very good. You know, one owes them a great deal. But one of the -- Again, you see, to come back to your point about the gap between the governor and the governors. If you look at -- If I if I can mention the States without being rude to the States. If you look at the way your communications are used, especially broadcasting, it seems to me to raise the question at once of democratic freedom in communication and then at the same time you've got you've got these massive chains of networks providing a product which is obviously saleable or they wouldn't be in business but not doing a whole range of things which a society like America needs doing with its communications. And you've got a -- What have you got connecting them with power? You've got a federal control commission, communications commission, which has no teeth and apparently doesn't want teeth just now, and a government which on the whole, for one thing, it's got too much to do, but on another thing the assumptions about freedom in a democracy are so muddled that I would say they've sold the freedom of American broadcasting to the market.

Studs Terkel So how does it compare, say, with Britain right now, as far as mass communications, specifically, say, especially television?

Richard Hoggart Especially television. I think the situation's better if I'm talking at home, of course, I mean if I'm talking to people about home and to British people, I'll grumble and attack like mad, one has to do, all the time. But our situation is better in that it's a it's a muddier situation and we have built in very powerful safeguards to make television do its best to program in the public service, and the result of this is that in England, there's always a tension between programming for mass audiences, entertainment programming, and programming for smaller audiences providing a much more diverse picture of what this country's life. So that on the whole you're much more likely to see programs which make you face realities than you are in the States.

Studs Terkel Of course, this leads to so many questions, Professor Hoggart, one, it seems with this new medium, television, mass communications, you would think so many facts are pouring forth to people, yet fact and truth are not always the same. And so we have the aspect of the individual. I'm sure you sense this, so many says, "What can I do. I am nothing." Has there been, as you look back and in all your research and memories, this lack of sense of personal worth that seems so prevalent today among so many people. Was this so, I wonder, in past generations?

Richard Hoggart I should doubt it, you see, it would come back to your old Negro woman and my grandmother and the challenges upon them were very severe but they were known, they were localized, they were recognizable. They were to feed the kids and get on with it and keep a home, and so on. What one has today much more and increasingly is a sense of, well it may be quite quite once quite prosperous, but when you get to the larger world, one has a society, a world in which there are problems which seem endless and totally insoluble and in which a person seems of very little use at all. So this induces a sense of, can induce a sense of, lackadaisical pointlessness. On the other hand it's a society which is in theory committed to the notion of what you call the spread of the fact, that everybody must be informed. But as again as you said, facts aren't knowledge, and what one runs up against then, especially in the way we've organized our mass communications, is the presentation of more facts than anybody can cope with in a way which reduces their real significance and makes them into objects for mere -- A special kind of entertainment. I mean one has to ask oneself how, first of all, one has to remark how much about Vietnam any American must know from television and the sheer coverage of, of, especially of the horrors. Then one says, "In what sense is this knowledge meaningful or usable? Isn't it in fact presented as a continuous succession?" I think there's a thing in the paper this morning which says that Vietnam is being used, it's been covered so much with the best intentions by American television that for people who can't cope with it, it's become a new form of Western. Well, that gets it in a nutshell.

Studs Terkel One man I remember coming across in during my adventures in compiling "Division Street: America" was a man who said, "I want to kick that tube in." He's "I don't want to hear about this. It leaves me cold. Why are they doing this to me?" He's "Let me have it just once a month and [outline?]. Once a month. I just want to paint my house and be left alone. I am cold to it", he says, and thus seems a new kind of feelingless being, you know, a good man, it would seem, but a feelingless being is coming to -- Almost Orwellian in nature.

Richard Hoggart Yes, this is -- There is quite a bit of documentation about this in the social sciences, again, much of it done in Chicago. There are various names for it, aren't there, dissociation, alienation. In some ways that feeling can be a kind of attempt to preserve one's sanity. It can be a kind of cowardice, but at any rate it seems to be one product of a society in which one's given, one's given all the evidence and no way of making it meaningful.

Studs Terkel Of course this leads to what obviously is your credo, your belief, which I share, is that life and culture, this word 'culture' has no meaning unless it's connected with life itself and it's this and we hear the word 'cultural explosion' used a great deal, and yet does it have any relation to the lives of the people involved, this is this is one of the gaps, isn't it?.

Richard Hoggart Yes, I think the phrase 'cultural explosion' is it's used here, of course, it's an American phrase, 'The Great Society' and all that. I think it's very confused the expression and can do nothing but bad. But harm. What they're really saying is that more people can hear more symphonies and read more books and OK, in a way, but my meaning of the word 'culture' isn't isn't that or that only, it's the sense of committed life, of originality, of authentic facing of experience, or exploring your life as honestly as you can and in what [that?] you can it's all this. Now in this sense, then the kinds of things that are offered as sort of culturally acceptable let's take a thing like, what is it called, the Lincoln Center in New York which is a great mausoleum, a dead elephant, to a monument, to a false notion of what constitutes the culture of a society. If if one's going to make it realistic one needs to look at the peculiar kinds of life and energy in New York and they won't be found in the Lincoln Center, they'll be found elsewhere and they'll be good and bad. But this is why it's so interesting in Britain just now, that in some respects, in some odd respects, there is more life in what you might call nonofficial culture than there is in the official culture, whether this is writing or music or art.

Studs Terkel Now if we could talk just a bit about this what might be called nonofficial or 'underground' perhaps misuse of that word, too, that something non-establishment dominated in a sense is happening or you feel that this has some significance, this popping, this popping around?

Richard Hoggart Yes, it hasn't as much significance as we're being asked to believe because inevitably in a commercial society if somebody comes up with a new idea it gets taken over and commercialized and becomes a nine days' wonder. But it has got this truth in it: that people who were previously unregarded as creators of cultural things, working-class people, provincial people, northerners, and so on, are now expressing themselves in ways without having to feel that they have to identify with or disguise themselves as southern, cosmopolitan, centralized, metropolitan middle-class culture people, they're being what they are themselves, this is the interest of the of the Beatles' revolution, that they're speaking with the accents of different kind of people and before this, 10 years ago in England, if you spoke with a Liverpool accent you were only allowed, so to speak, on the national stage if you were regarded as a comic. You weren't taken seriously and you imitated working-class voices. It was supposed to be funny. And then one way this is shown is that the Beatle -- When I say they speak with the accents of their kind of people, I don't just mean the actual dialogue, dialect they speak, I mean the things they say, their response to experience, a peculiar brand of wit and irony and refusal to conform, this is very much a Liverpool product, and therefore what one's having injected in a small way to a country which has always been rather bland towards itself, is a is a tradition which it, which we haven't really known we had.

Studs Terkel Do you feel on the subject, you feel that since the welfare state and since loss of colonies and this sense of freeing oneself from this fantasy, you know, of superiority, that the class, have your class structures have really broken down?

Richard Hoggart No, no, they haven't. I've been talking because you've been putting the questions in a way that tempted me quite rightly. I've been talking on the optimistic side. If I put the other side I can soon get quite pessimistic. What I think's happened is this, put ever so briefly: that the class system as we knew it, first, second, third, upper, middle, lower, that in some ways is less evident than it used to be because people have got very self-conscious about it. But you don't remove a thing like this overnight, you don't remove it in ten years, it's about 600 years old in England. And what's more, you don't really remove it just by wishing to remove it. And on the whole people don't want this removed. People have a very strong sense of distinction, of difference, and want to be a bit separate from somebody else. It's in our bones in some ways. So what's happening, I think, is that although we're all going around with our hands on our hearts saying that we've gone classless or that the whole country's middle-class. I think the actual deep-seated sense of class is hardly touched and certainly social scientific evidence suggests that people still feel themselves quite firmly classed. They wouldn't say so. So what form does it take? I think it takes a form nowadays of trying to get at that little distinguishing marginal differentiation, that difference of status which will mark you off. It has to take new forms. But let's take one obvious instance. If this country had been really going classless in any pervading sense, you might have expected that the public schools would have suffered because for my money they are the most entrenched perpetuators of the notion of a class society.

Studs Terkel We should point out public schools here in England are equivalent to private schools in America.

Richard Hoggart And in fact the British public, that's your private, schools these residential schools which are schools for the training of gentlemen and the sons of gentlemen are more prosperous now than they have ever been in their history. Why is that? Why in a time when, on the face of it, we we should be producing finer and finer state schools, what you call public schools, and in some ways we are doing. Why is it that people in a time of high taxation will nevertheless somehow find the money to send their kids to schools like this? Why is this when we're supposed -- it's supposed not to matter where you went to school? The answer is very simple; that in a period when the old distinguishing markers of a society are beginning to blur, when it's not so easy to tell what class you come from because even girls nowadays tend to dress alike, they're all smart, they all go to Marks & Spencer's and so on, and accents are less heavily marked, and so on and so forth, and so on. In such a period the one thing, the indefinable something you can get if you want to separate yourself, is that air of confidence which an English public school gives. It also helps very much for getting jobs often, but there's a something, an air of knowing that you're on top of the heap and parents are buying this. Parents of all sorts of classes, if they have got the money.

Studs Terkel This is fascinating, what you're saying. This indeed may be true of America now, but here perhaps it's more dramatic because we think of England as a class-full society. I came across several people, the other day a porter at the hotel says he wishes it were pre-welfare state. He'd know his place better. I remember this couple who owned a pub several years ago even though their daughter went to the university, are better off materially, wishes it were the other, they would seem to know their place as servers better. Interesting.

Richard Hoggart I think yes, it is interesting. I think what it points to is this, that in a society which is class-structured it can be easier, less anxiety-ridden to live, even if you're at the bottom of the structure, because as these people told you, they know their place. You know, this was one of the points made by, after all he was an American by birth, T.S. Eliot in his book "Notes Towards the Definition of Culture" in which he said roughly that it's better to have a society in which you know by birth what your class is, because then you're not ridden by anxiety to move out or blame because you didn't move out, you know your place. And there's a kind of comfort in it. I think this is felt by a lot of people in England, not just by the people who make the most noise who tend to be the anxious middle-class and inevitably they're the ones who are always ground between the two, but also by people like the ones you've quoted who are working-class but find now that they can't always be sure that they're recognizing a gentleman when they see one and so on, it's a very uneasy feeling, and it is after all rather difficult to live in an open society.

Studs Terkel So this very -- It's almost as though there is freedom, with quotes about it, suddenly offered on a platter, it would seem, and the person so accustomed to bowing and to saying "Sir" doesn't have to say it still at the moment is lost, isn't he?

Richard Hoggart Yes. One of the common phrases apart from the one you quote here which is that when you knew your place is the very old phrase I don't know what the world's coming to and I know dozens of people who would use that and what they really mean is, I knew where I was, I would say a lower-middle-class schoolteacher and now I haven't a clue, everything swirling around me, and another [angle of it is?] university teaches themselves. At one point about 30 years ago, when you went to university if you were working-class, the assumption was that you were being trained to enter the professional middle class. Nowadays students come along and very often they're revolting against this assumption, they're coming in deliberately looking working-class or deliberately being 'beat.' And it's it's difficult for some university teachers who regarded themselves as the bearers of the traditional intellectual heritage in traditional high bourgeois terms. It's difficult for them to face a class of people who look, as they say, like louts. Then they discover that they're quite bright but they're not buying a social package along with the intellect.

Studs Terkel It would seem that in these 10 years since your book, "Uses of Literacy" was written, so much is happening and you say it can go -- It's working two ways, there are two streams at work. You feel optimistic about one aspect of the youth, their liveliness, of their costume, the originality of their language. At the same time, you're quite pessimistic about things haven't quite changed that much and if changes are, that this. the banality of mass entertainment. I'm very curious because your book deals with this, too, mass entertainment in the past. Magazines read by the non-academically trained people in contrast to what they see today, more slick and more glossy. You're implying today's may be, if anything, even more debasing.

Richard Hoggart Yes. it's again like your your colored woman, isn't it. I think that the newer magazines, because they're reaching bigger and bigger audiences and can't root themselves in specific areas of anybody's life, tend to settle for a central area which is rather bland and processed and unreal. I think this is a movement and I'd be prepared if it weren't for the laws of libel to run right through the history of English women's magazines and show you how it alters like that. But this is a process you've seen in the States.

Studs Terkel Yes. I'm curious to know what, because this is the question your book deals with this aspect. I remember somewhere in your book you always speak of the minority no matter what group they're from and there's the romanticizing, say, of course, the "Jude the Obscure" but it seems you're saying always there were these well-read men, these literate men, will their kind disappear? You know, the this this this individual who was always against the grain, will there be less and less of them, less and less of your grandmother with her illuminating gesture, you call, a certain uniqueness in each person.

Richard Hoggart Well, my my guess is that the number of people, the proportion of people who are prepared to step out of line won't alter that, this is part of human nature, I hope so, otherwise we really would be in a bad way. But then when you said that you're in danger of saying it's always 6 percent and they carry the weight for everybody else. I don't think it's quite as simple as that. I think that the figure of those who actually will challenge, argue, step out is pretty small. I think it's bigger than we've been used to thinking. See, one of my basic assumptions which I haven't said so far is that the English have been an insufficiently expectant nation. I mean we're a very dogged nation and we are a very flexible nation and we're very resilient in all kinds of ways. But in a curious kind of way we have [damp souls?]. I mean we we don't expect very much we don't really believe that more than about 5 percent will ever really shake themselves. I think the rest are pretty good. They're like the infantry in a war they do what you tell them. And I think one of the great, one of my own assumptions is that there are more people, far more, who, if they're given a chance will, when they see what seems like the truth, stand by it, even if it costs them something. I don't know what the figure is, but it's a lot more than 5 percent.

Studs Terkel You feel there's more more and more of these people who will be questioning whatever the established values may be if these values are cock-eyed. You feel there are more such.

Richard Hoggart More than we've got. I don't know what the optimal figure is but I do know that if I'm teaching and I don't give people a chance to see what it is they're questioning, then I failed.

Studs Terkel Of course, as you say this, I see a quote in your book, "Uses of Literacy", Bishop Wilson a couple of hundred years ago saying, "The number of those who need to be awakened is far greater than those who need comfort." Well, it would seem that Bishop Wilson's comment 200 years ago was so prescient that at this moment it could be made. Comfort--

Richard Hoggart Absolutely, yes. Those who need comfort or those who are aware of troubles, difficulties, challenge. But you see, I spent my first 15 years teaching out in the field in adult education and what you meet there are people who have escaped all the ladders of advancement but come to these classes to challenge, question, ask about their society. These people exist.

Studs Terkel They do. Now, see, I realize you and I, being contemporaries, I'm a bit older than you but nonetheless, we remember, you remember your grandmother, pre-technological, a pre-technological age woman, as I know these elderly Negro ladies and the [same?] my grandmother. You see, it's difficult for us to look without some trepidation upon what is happening technologically and yet we may be somewhat jaundiced in that view because of this.

Richard Hoggart Yeah, I think it's a fair comment when -- you know, when -- Especially as you get older and your arteries begin to harden then you begin to wish the world wasn't changing so fast and you find it difficult to understand your own children and so on and so forth. I think there is this danger and then if you're not careful you'll fall over backwards into the other thing which is getting desperately 'with it' and contemporary. I don't see any any way out of it except to say that one goes on doing one's best to stand up.

Studs Terkel You know, the last line of your book itself, "The Uses of Literacy", by the way, I think it should be read and re-read today in the year 1968, I say, and of course, this is perhaps the -- We hear the word 'freedom' used a great deal. We hear the word 'facts' coming through, we're being fed all this information. And the last line is "the members from the whole society -- members will still regard themselves as free" but go back further, "the great new classless class would be unlikely to know it, what has been happening to inner freedom being lost. Its members would still regard themselves as free and be told that they were free and yet indeed be perhaps Orwellian --"

Richard Hoggart "Bound." Yeah, I think this is the I think this is still the great challenge and I don't think that on the whole in Britain or the States we've come much nearer facing it.

Studs Terkel If we could just perhaps just be very free in talking about your book itself and the various aspects of it, this is dealing now with your own thoughts of now, the technological age, how free is a man today in contrast, say, to his father. He's much materially better off, certainly, but how free is he, we come back to entertainment. We come back to what he sees and what he reads and the disconnection with life itself. Is it because of the, also the rootless nature of our communities, too, that once you point out there once was a solid neighborhood, a man was known as a grocer, a man was known as a barber.

Richard Hoggart Yeah. Yeah. I think this is one of the one of the forces and I don't see that it will become less because it's in the nature of modern societies that they do become more mobile, more centralized, more more stratified by the job you do, not by that you're belonging to a neighborhood and this is all the movement, it's there in Chicago very powerfully, as you know better than I do, and in New York, and all the great cities of the world. So then we have to learn how to live in this in a more open society. And if one -- Attendances are all rather somber but if you actually look at people and see how they're getting on, it's surprising how much they put down their roots even in a 30-story block of flats. In the end, family, children begin to make connections but one can build in such a way that those connections are very hard indeed to make and then you do have a really awful breakdown and you've you've you've remarked on that in "Division Street: America."

Studs Terkel When you talk about personal relationships, too, you mentioned that you have several sequences concerning attitudes toward sex, you know, you speak a great deal of sexual freedom yet you point out something rather interesting in the voyeurism in some of the books today, in contrast to the whole at 10, 20, 30 types -- Sort of a new development here that makes sex almost a thing.

Richard Hoggart Well, again a large urban society is going to throw up a mass of voyeuristic sex. It's bound to because it becomes a sort of product. The end at the end of this the end of this line in the States apart from the 'underground' stuff is "Playboy" and we have our equivalents and so on. I think any full survey of sex, sexual change, attitude change, towards sex in Britain today would have to set that against what seems to be a strange change going on among younger people in their attitudes towards sex, and had -- This evidence we have suggests that they're not promiscuous. On the other hand, there does seem to be among quite a number of them much less social fear of sex than the tendency for girls once they're going steady with a boy to have full relationships with him and not feel guilty seems to me to be a real change. I'm sure it happened in the '30s but it was always done against the grain. It was done as an underground thing or as a sort of guilty challenge to society. One of the striking things if you read and listen to young people talking about it today is if they decide that this is what they will do, they do so without, as they always say, feeling moral about it; I mean they don't feel, that they feel that they know what the stakes are. Which I think is, actually I'm trying to make a sharp distinction between I'm not saying they're having more extramarital sex, and I'm not either praising or blaming now, I just want to try and get my finger on to one change it seems to be that if they decide to have extramarital sex, then they don't feel that they are opposing some moral imperative. They have rejected the moral imperative of the society. They have others.

Studs Terkel Here then is a breakdown or is a challenge at least to the Victorian setup, the inhibitions. There again is a breakup, breakdown here.

Richard Hoggart Yes. I think this is a very important one and it's much wider than sex that the sorts of inhibitions which were established right through the last two or three hundred years and which at bottom were a means of maintaining as a society with what it needed and with the people doing the jobs they needed and marriage is the center and all that and which was therefore supported by a whole lot of religious injunction. I think whenever we get around to measuring the extent to which this has been eroded among the present generation of intelligent young people we'll probably be surprised and, you see, again I am not saying in any way that we have a generation of immoral young people. I'm saying that they are in a way writing their own ticket often very carefully.

Studs Terkel You spoke of religious injunction, which naturally leads to the subject of attitude towards religion. Here, too, has been a revolutionary change, isn't there?

Richard Hoggart Yes, yes. I don't see much interest. There are, of course, in universities pastors and [unintelligible] there are students who go along, too, to services and so on. But in my experience it's true that most of the intelligent students, they're not anti-religious. They're just not interested. And I myself am agnostic. But if if I were beginning to be interested in religion I'd find it difficult to know where to go in Britain because one doesn't look for any kind of searching or probing of religious issues in the Church of England nor really in the non-conformist churches nor in the Catholic hierarchy as it's established. I suppose the most lively place which is a lively area in religion which is trying to come to some understanding of modern society and of the place of religion in it is the renegade wing of the Roman Catholic Church.

Studs Terkel Where social action becomes --

Studs Terkel And again here, just as you speak of culture and life, they speak of religion and life.

Richard Hoggart Yes, they do indeed. And of course they're in trouble, when Charles Davis is now in the States and so on and so forth.

Studs Terkel Bishop Roberts, too.

Richard Hoggart Bishop Roberts. And you can run through a list like that.

Studs Terkel So this leads to, where does this leave us? I mean using your your book "Uses of Literacy" as the catapult of this conversation and the substance of it, you might say. The Matthew Arnold quote years ago, [he may?] also the few who are looking will have a hard time of it, no matter when they live. You say there are more perhaps than there were then. The young are writing their own ticket. What are your own observations now in the year, some 10 years after the writing of the book?

Richard Hoggart What particular aspect do you think?

Studs Terkel Just this whole matter of the man, the individual and the society, of mass communications, and his knowledge or fact, truth, feeling of potency or impotence.

Richard Hoggart I alternate. I try to strike a balance between optimism and doubt. On the optimistic side, people have shown greater capacity to cope with the material which is thrown at them with greater resilience even than I'd thought. I talked about resilience but even more than I'd thought. And this has been led chiefly by younger people. On the other hand I think the -- One has to warn oneself that this kind of thing can itself be chewed up into the system, and become merely an imitation, a simulacrum. I think the basic issues remain and they come back to what we said right at the start of this conversation that the biggest single problem is a sense of incipient meaninglessness in life. You can have a prosperous world, you can have a decent house and like the man you quoted earlier, you can say, "Well, I'll spend my time painting my house and shut the door on life." But you can't because what you've done then is bought what the society's asked you to buy. They even let you have cheap an electric toolkit to do the job for you. But if they want you to go to Vietnam or wherever it is, you'll go and you wont even ask questions about why it's all on. So there's no escape from this one and I don't see much. I don't see much sense of this problem. I don't see for example in universities here or in the States in a really tough sense that one is asking questions about the nature of a society not among the institutions themselves. One sees students themselves creating anti-universities to ask the questions so that overall and I'd have what you might call a qualified optimism with a long-term doubt about whether we're really shaping up to the questions which which which most should concern us.

Studs Terkel The values of, the very values we live by.

Richard Hoggart Yeah. Yeah. They could go and we don't sufficiently recognize what they are.

Studs Terkel Perhaps before I say goodbye now to you, Professor Richard Hoggart, and again remind the audience of this book and its availability, "Uses of Literacy", and is of now, to use a phrase of the kids, it's a 'now' book', as much as it was a 'then' book 10 years ago, a now book. This last comment. I know it's difficult for us to leave this, our boyhood. Your memories of your grandmother and your comments that she made to me are so vivid and colorful. The the wisdom that is there, even the phrases themselves had a theatricality about them. And this is hard, I suppose, for us to leave [and our?] contemporaries, you know, that something new will be coming, but not this anymore.

Richard Hoggart Yes. Yes. As you've said twice we've got to be careful of nostalgia. On the other hand, it would be wrong, wouldn't it not to recognize this because for you I should guess from reading "Division Street", and for me, I know, something of our peculiar kind of energy and openness and responsiveness to the variety of life is drawing upon those roots and they in a way they taught us how to how to cut through.

Studs Terkel This is my last question and it's my obsession and I would suspect yours to some extent: continuity. That as a rootlessness you know there's a phrase that artists and critics use, 'tradition of the new', the artist is beginning, he's right -- In fact, he's building his own compass. Is this aspect of continuity, many of the young feel there is no past at all and this, do you sense in this perhaps a danger or is this perhaps just a --

Richard Hoggart Yeah, it is a danger. One of the one of the good things is that when younger people start getting married and having children then they draw up on their roots like mad. One can't escape it, it's a myth to think one can. And I for one I suppose like you I'm not going to try to because I know that what is me now in 1968 although if you see me you say, a professor in a British university. What is me is X generations of British working-class peasants and this is in the very way I respond to experience, it's the way I, the way I kick back if somebody is trying to do me down, it's the way I -- All kinds of things, good and bad. I mean, I can I can feel those in my bones and I shan't understand my own future well if I pretend that they don't exist and this is true of everybody. You can see it in Harold Wilson, the prime minister, and you can't understand him without a sense of continuity. It's interesting when there's talk about him in England; of course, he's much disliked, especially by the conservative press. But in fact they talk about him as though he was born yesterday out of a plastic bag! In fact, if you really want to understand a man like that, you can take his route right back to the north of England in a certain way and therefore the sense of what that American expression 'the available past' is one of the most important senses a man can have before he can even begin to be modern.

Studs Terkel So what you're really saying if I interpret you correctly, Professor Hoggart, is that even though they speak of rootlessness, continuity is there, whether the whether the man recognizes it or not, it is there in him.

Richard Hoggart Yes, absolutely. And if he doesn't recognize it he will be denying some of his own best strengths.

Studs Terkel Professor Richard Hoggart, thank you very much indeed. And any comments, any anything you care to say that we haven't touched upon, any any aspect of --

Richard Hoggart No, all I would like to say if I may, is that I enjoyed "Division Street" enormously and of course was struck by the similarities in background and approach. I mean clearly in some respects we are more compatible types and whatever have been imagined if you looked at our different backgrounds. But the fact is that we both have a similar kind of taproot to draw upon.

Studs Terkel So 'taproot', of course, is the word and it's there whether recognized or not. Thank you very much indeed, Richard Hoggart, and the book is "Uses of Literacy" and must reading it seems to me for everyone. Thank you. Professor Hoggart's book "Uses of Literacy" is published in England by the Penguin Press, their subsidiary Pelican Press was a paperback. I hope it's available here. In a moment, after we hear from Mel Zelman in a moment, he's shifting the tapes now. I'd like to finish with about 10 minutes of the man who was a night porter at the hotel where I was staying, the Whitehall Hotel in Bloomsbury Square and one evening when I was home in my room rather, he was on the floor below and he decided to talk. He hadn't talked, no microphone in his life. He wanted to, and I had encouraged him, of course, and he liked the idea and it's interesting. We'll talk about him in a moment after we hear a word from Mel Zelman and then I'll introduce Jack M., the porter.