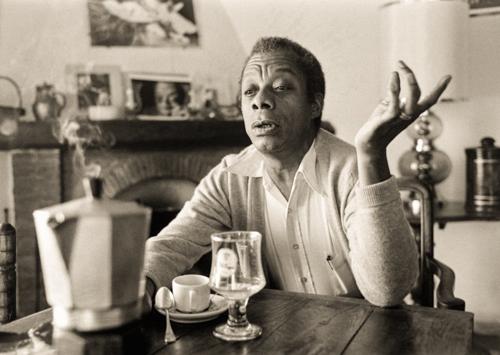

Noted Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl discusses his most recent book

BROADCAST: Oct. 9, 1981 | DURATION: 00:52:38

Synopsis

Noted Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl discusses his most recent book "The Tigris Expedition: In Search of Our Beginnings" in which Heyerdahl and a crew of 10 men built a reed boat in Iraq and sailed it through the Persian Gulf, around the Horn of Africa, to Pakistan and eventually the Red Sea. Their goal was to prove that the ancient peoples of Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley could have been in contact through marine trade and migration. Terkel and Heyerdahl also discuss problems the crew encountered, what they learned, and the contemporary political climate in which the expedition took place from November 1977-April 3, 1978, when the crew burned the Tigris in Djibouti in protest of the wars ravaging the Middle East. The interview also touches on Heyerdahl's previous expeditions, Ra, Ra II, and Kon-Tiki.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel Seems to me one of the most probing of men, I'd call him a seafaring statesman, Thor Heyerdahl, whom you know, of course, from his adventures on the raft of balsa wood, Kon-Tiki, across much of the Pacific to recreate a trip centuries ago, thousands of years ago by others as well as his Ra expeditions, I and II, across the Atlantic as pre-Colombians did long, long, pre-Columbian, pre-Erikson. And now his most recent and longest, and perhaps most revelatory of all voyages in the Middle East called the Tigris Expedition. Wanted to know, of course, Thor Heyerdahl is more than just a seafaring man. He's been called an archaeological buccaneer by The London Observer, someone else called him "Playboy of the Ocean." But I think he's a statesman of the sea and seeking to find out from the past about our present, but mostly about how we are today. And so his adventures, it was the world on that ship the Tigris made of berdi reeds. More of this in a moment. The name of the book is The Tigris Expedition, Doubleday the publishers. In Search of Our Beginnings, the subtitle. Dr. Heyerdahl my guest in a moment after this message. [pause in recording] Dr. Heyerdahl, it was 10 years ago you visited Chicago after you completed your book describing your voyage, The Ra Expeditions, and toward the end of the conversation, that hour 10 years ago, 1971, you read this passage, we hear you.

Thor Heyerdahl "We threw a last look back at the vanquished ocean. There it lay seemingly boundless, as in Columbus' day, as in the golden age of mighty Lixus, that is a ruin city in, on the Atlantic Coast of Morocco, as in the days of the roving Phoenicians and intrepid Olmecs. How long would whale and fish gambol out there? Would man at the 11th hour learn to dispose of his modern garbage? Would he abandon his war against nature? Would future generations restore early man's respect and veneration for the sea and the earth humbly worshipped by the Inca as Mama Cocha and Mama Allpa, Mother Sea and Mother Earth? If not, it will be a little use to struggle for peace among nations and still less to wage war onboard our little spacecraft. The ocean is not endless. We jumped barefoot ashore at the other end, the ocean current rolled on alone. Fifty-seven days, 57,000 years; has mankind changed? Nature has not, and man is nature."

Studs Terkel So the last passage, a very moving sequence [fades out]. So I was thinking, Dr. Heyerdahl, 10 years ago, you asked that question. The challenge. Ten years later now.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes, it is a fact. And one good thing has happened. Speaking as a navigator, I feel that, when you're in trouble, when you're heading for a reef, you have to do two things. First of all, you have to open your eyes and realize that you have troubles ahead. Next, you have to do something about it, change course. I think that 10 years ago very few of us had opened the eyes. Today I feel wherever I go all over the world that the common public and the decision-makers have started to realize that we have to do something about it. This is not going to go the right way. That is one big step ahead. But still we have to take the next step, and that is to do something

Studs Terkel Well, to do something about it, that's, that's the big question. Ten years ago, when you were describing the crossing across the Atlantic, now it's 1981. Suppose you start at the beginning of this new adventure, the Tigris expedition. We start somewhere where the Euphrates and the Tigris meet.

Thor Heyerdahl This is correct. In what today is southern Iraq. It used to be known as Mesopotamia, and there still further back it was known as the Garden of Eden by the ancient Hebrew and Muslim who believed that this was the place where mankind was created, and where Adam and, and Eve lives. Of course, today archeology goes much beyond these periods, and much has changed in the area. But it is a fantastic place. It's still full of atmosphere when you go there. And I think that in this very place very little has changed the last 5000 years, just large areas of reeds, and probably the only place where I've been where really civilized people live much as they lived 5000 years ago. The marsh Arabs that live hidden in between these reeds

Studs Terkel The marsh Arabs helped you build the boat.

Thor Heyerdahl They did, they did, and they also gave me the information I really needed to be able to undertake this voyage.

Studs Terkel Let's start at -- why you chose this region. You, you had two previous long trips, one to prove to Europeans that they're not the only one, that before they came along, before Columbus and Erikson, there were some traders from the Middle East or somewhere who'd crossed the Atlantic. And you prove to other Western explorers that South American Indians could cross, make a big crossing on a balsa wood raft in Kon-Tiki. Now you're out to show what?

Thor Heyerdahl No, I was out to show that we have underestimated in many ways the intelligence of man 5000 years ago, and we have drawn a wrong conclusion when it comes to the traveling possibilities of man the day when civilization suddenly emerged as far as we know, about 3100 B.C. at three places roughly simultaneous: Mesopotamia, the Nile Valley and the Indus Valley. What is interesting is that in this early period, these people had only reed boats. The boats, to judge from their art must have been the same type in all these places. But the material was different. When I crossed the Atlantic with the Ra, we used papyrus like the ancient Egyptians, a reed that used to grow all along the Nile, and which was widely used in the Mediterranean world in that early period. No, there is no papyrus at all in Mesopotamia. They had a different reed, botanically it's called "typha," but the Arabs call it "berdi." Now, science had tested this reed and found that it will sink after two weeks. So it was concluded that the, the Sumerians, with that kind of vessel, could not have left the river. The boat had to be dragged ashore, and pulled ashore and dried every once in a while. Now, this did not match what the Sumerians themselves said, because from the earliest period they were great merchants, merchant travelers and sailors, and a lot of the written tablets, they left thousands of clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform script which archeology has deciphered, and an overwhelming majority of them speak about trade and business, and there are even some of them are contracts between captains and the merchant men ashore as to who is responsible if the ship is wrecked and the cargo is lost, et cetera.

Studs Terkel Thor Heyerdahl, you have raised some, one of most fascinating of all points and challenges. You were told by the archeological findings, the scientists, that the ancient mariners could not make a long, several thousand mile trip, as you eventually did, with reed boats, whereas ancient tablets and legend and story told you they could, and you believed, you followed the hunch of the ancient tablets rather than the anthropological findings. This raises quite a question, doesn't it?

Thor Heyerdahl Well, I knew from experience that it is possible for science to make errors, particularly when it comes to reconstructing the past, where there are so many possibilities. I knew that when it came to the balsa raft, balsa wood, if you put it in water, will sink, but what science had overlooked was that people in those early days did not buy dry balsa in the shop. They went into the jungle, cut the tree, and when the tree has the sap, it will not sink. It's like impregnation, and that's what we discovered, and the same with papyrus. You can leave papyrus in a bathtub, as they had done at the Papyrus Institute in Cairo, and it will start to smell and rot after two weeks, but build a boat and it's

Studs Terkel But the marsh Arabs taught you something, too, they told you that a certain kind of reed grown during the month of August!

Thor Heyerdahl Exact -- what they told me was, I asked them, "Is it true that this reed of yours," which they used all the time today, "that it will absorb water and sink?" And they said, "Yes, but not if you cut the reeds in the month of August, there is a season." And in that particular season there is something inside the reed, so I believed in them and the ancient tablets and we built the

Studs Terkel Now you're going to recreate a possible journey of thousands of years ago. Now, suppose you offer us what you had in mind originally, 'cause you improvised during it. What was the journey you had in mind?

Thor Heyerdahl The journey I had in mind was that I was quite confident that this vessel would float. What was a major problem was that where we started this trip would mean that we just couldn't drift with the wind and the current, like we did with Kon-Tiki and Ra. We had an open ocean in front of us, and the wind and the current had one direction, but not so off Mesopotamia or Iraq. That means we had to navigate through the Persian Gulf to get out into the open ocean. And this was a major problem that we felt immediately. A reed boat of this type has no keels, so even experienced navigators said that you cannot steer it, you'll just drift sideways. And it took us quite some time before we, we really learned how to maneuver steering oars and sail in such a way that we could tack into the wind. But when I set out, I just wanted to see how far could we go and how much could we navigate.

Studs Terkel Of course, you wound up along the Horn of Africa.

Thor Heyerdahl That's right, and, and once we found out that we could navigate, then I tried to tie together the three early civilizations

Studs Terkel There were three early civilizations: the Middle Eastern

Thor Heyerdahl The Middle Eastern

Thor Heyerdahl And the, the Red Sea, Egyptian.

Studs Terkel So they wound up about 4000 miles along the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean and place you could not stop we come to, because the world of nine-- the 20th century was also trespassing upon your idea, we'll come to that. So here's the trip. Now, and you called upon your old friends from South American boat builders, Indian boat builders, to help also.

Thor Heyerdahl This is correct, because we know from early art, cylinder seals and the reliefs and frescoes how these ancient boats were built. But there are nobody there today that know how to build them. They're lost. A few 1000 years ago, at least a couple of 1000 years ago. The only place on this planet today where people know how to build them, is Lake Titicaca in South America. So I had to bring Aymara Indians to help build a vessel from Lake Titicaca.

Studs Terkel Now you know them from your Ra adventure. You said -- no, no, from your Kon-Tiki adventure.

Thor Heyerdahl No, from the Ra.

Studs Terkel From the Ra adventure, yes.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes, as a matter of fact, Ra I was built by the Duma from Central Africa, and it didn't work. The ropes busted just before we came to America.

Studs Terkel Of course, what you're also telling us, this quite marvelous book by the way, The Tigris Expedition," full of adventure and trials and perils. You're telling us that civilization is not exclusive property of Europeans alone.

Thor Heyerdahl No, we and -- should bear in mind where we got our civilization from. We all realize that European civilization started with the ancient Greeks. And those who know a little bit of archaeology will realize that the Greeks again got it from the island of Crete, and that the people in Crete got it from the Phoenicians and the Egyptians. Now, the Phoenicians got it from the Hitites, the Hitites again from the Assyrians who got it from the Sumerians. It all started a little more than 5000 years ago down in southern Iraq with the Sumerians who were the first to start writing, complicated architecture, metal work, they wrote the first real epos, and they were the first real businessmen.

Studs Terkel And so we come to your crew. Now we come the -- 11 including yourself. Now, here is reality and a metaphor at the same time, the crew from different societies.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes. First of all, we know that in ancient time different people were mixed together on a boat for many reasons. One of them at that time was definitely to have somebody that could interpret. From Leif Erikson's voyage, we know that he had a Turk on board his boat from the first circumnavigation of Africa a few 100 years before Christ. This was an Egyptian enterprise with Phoenician sailors and certainly traveling the Sumerians would also visit foreign land, they would mix their crew. And I did it partly for these reason, but still more because I wanted to show that men, irrespective of political ideas and ethnic background, religious beliefs could live together in peace and collaborate even on such a limited space and under stress as we had.

Studs Terkel So here's a crew of different societies, different [societies?], different ideologies. Because there was a Soviet guy on ship, a couple of Americans, there was a Japanese guy, there was an Italian mountain climber, there was a West German, a couple of young Scan-- you and a, a young Norwegian and a young Dane, and there was a Muslim.

Thor Heyerdahl There was a Muslim, and one of the Americans was a Jew, so we really had what people would think ask for trouble. But we didn't get it.

Studs Terkel Of course, your, it's, it's incredibly moving, the relationship of one to the other during the moments of tension, tension from the sea or the elements and difficulty getting equipment. Here, so here was a United Nations -- oh, United Nations flag.

Thor Heyerdahl We actually sailed under United Nations flag because I had this mixed crew on board. And to me this was perhaps the most rewarding part of the experiment, to see how it all worked out, and to see that whenever a man lost his temper, and that always happens, and it happens even on the reed boat, it would be for some completely silly little thing that somebody has spilled honey or sugar in the sleeping bag or of another, or he had hooked his pants with the fish hook or something, and he would explode, and it would be all over in very little time, but we made a point at meal times when we were all sitting together to discuss politics and all the things that you would think would lead to somebody hitting the other's head. It never happened. We all discovered that there is a reason why the other one believed this. We don't believe it, but that's not the reason to kill the other man, or to start fighting. We came on board with difficult -- with different beliefs, and we left with different beliefs but as best of friends.

Studs Terkel Could you continue with this, 'cause perhaps you're touching one of the keys to your journey. You -- not that you were recreating an ancient past, but you're living at a certain moment when we're on the precipice, you know, with the madness of the loony nuclear arms race, particularly between two superpowers. On that boat are people representing the two superpowers, plus the others. And we're talking about getting along no matter how ideas may differ.

Thor Heyerdahl I think that if people sit together and pre -- are prepared to get to know each others, they will realize how much we have in common and that there is something wonderful in every human being if you look for it. I think the trouble in the world today is basically the fact that the political leaders are far apart in every sense and they don't get to know each others. They are just hiding behind the guns instead of like the common man creeping underneath the gun and shaking hands and say, "No, I don't agree with you, but we must find some way of living together. This planet is getting so small and they're getting so many of us. So if we start fighting, I mean we'll sink. This is actually one thing I noticed on board the vessel, which was really touching to me, was to see that we had rough time, storms, and night watch could be really, you were half-dead by the time it was another one to take over from your turn. I saw more than once that a man sneaked out of the cabin before he was called because he knew that this chap up on the bridge was getting tired and he relieved him secretly. And I tried to understand why this will got that way. And there was a double reason. And one hidden reason was that we all knew that if one of the men is getting really worn out or ill, well, then we're all in trouble. We depend one

Studs Terkel So this is what it's about. That you said if we fight, the ship will sink, is the phrase you used. The ship is the Earth. The ship was the world, so we're interdependent whether we want to or not. So there has to be the cooperation, not because of just altruism alone, because of self-interest.

Thor Heyerdahl That's exactly what I feel. If you're really interested in, in, in having a happy future for yourself and your family, then I think the best way is to try to find a way out of all the problems we have today.

Studs Terkel And now we'll come to your adventures, I mean with -- Thor Heyerdahl my guest is the most recent book, the one we're discussing, the Tigris Expedition, published by Doubleday and the subtitle In Search of Our Beginnings, you might add a subtitle, And We Trust Not Our Ending Either. So a search of our beginnings and the old theory again, the key theory about if we know where we came from and how we got that way, we'll have a better idea of where we are and where we might be going. So we continue in a moment with the adventures and the discoveries and revelations of Thor Heyerdahl and his colleagues aboard the Tigris after this message. [pause in recording] And we continue with Thor Heyerdahl and his adventures on The Tigris Expedition, the title of his most recent work. And so the adventures themselves now, there are so many. By the way, how you did it, there, there were sort of the, the trials of Job to get the equipment to begin with.

Thor Heyerdahl Well, it was an, it was a difficult place to organize an expedition, Iraq, because, first of all, it was a closed country. Tourists were not allowed, and to get permission to bring in people indiscriminately from different countries. As I said, one of my men was a Jew, But I think that the the government, thanks to pressure from the scientists, realized that there was a purpose to the experiment, so they were extremely helpful. And I got carte blanche to bring in anybody I wanted and to bring in any equipment. But it wasn't all that easy anyhow because the meeting place of Euphrates and Tigris is way out in the wilderness in, among, among the reed swamps, and we certainly did have many obstacles before we got together and down the river.

Studs Terkel Now, you're talking about different governmental -- the countries, and other ships, vessels, there was an understanding -- you ran into a, there was a Soviet tanker, Captain Igor. Now, one of your crew is Soviet and someone thought, "Hey, maybe you're in danger 'cause the Soviets" -- quite the opposite was the case.

Thor Heyerdahl Yeah, well, that shows how it is easy to distrust even the best fellow because you have preconceived ideas. This was when we, at the beginning of the voyage before we had really rediscovered how to navigate, we were drifting into the reefs of Failaka, and it might have been the very end of the expedition because we lost both our anchors, the wind was strong, and the ropes busted, so we were heading really for a very bad area, and three doves came out, and we knew from the sailing direction that this was a place where we shouldn't have been, because it's saying never venture into this area without armed guards. And these people wanted ransom. Otherwise

Studs Terkel Now, these were pirates.

Thor Heyerdahl They were, you could literally call them pirates. Well, they probably were. They were smuggling people professionally

Studs Terkel Now, where were they from?

Thor Heyerdahl They were a very mixed lot, I think, mixed from Pakistan, Iran and Kuwait. And they were smuggling people as we were told later, into this uninhabited side of Failaka island and from the other side, they could take the ferry boat right into Kuwait. But when we were in trouble, we try to, on our little radio, to contact Kuwait but they didn't hear us, but a Soviet freighter heard us, and they knew that I had a Russian on board. So they came right up to the reef, and Captain Igor and his crew managed to tow us out of the reef and pulled us to Bahrain, so when we came to Bahrain, the Coast Guard came out and kept on sailing around us and around us, and we had a message that we were welcome there, the Minister of Education was waiting on the wharf, but they didn't take our tow, so not to drift away we were hanging in the rope of the Russian steamer. So we learnt in then that they didn't help us until the Russians let go because they thought we were captives.

Thor Heyerdahl So when, when we were let ashore, Captain Igor asked to get into port also, to spend the night there before he went out. But he was not permitted.

Studs Terkel So we're talking about fears, aren't we?

Studs Terkel The fear that is there, even fear of someone who may be friendly.

Studs Terkel We're talking about that aspect of it.

Thor Heyerdahl And I think Captain Igor was really very brave, because he took this chance with his ship and his crew, even without authorization from Moscow. He sent a cable later explaining what was going on and got a, a, a clearing.

Studs Terkel But these are all parts of the adventures you're having, and also there's irony here, you're going into a pass sailing on a reed boat, yet something comes over the radio, advice to a plane that's going about 1000 times your speed. You know, you, you're in a time of a present that is technologically incredible.

Thor Heyerdahl Well, that's true. It, we are really in a transition period, in any case, and in our case, I mean, there was a time span of 5000 years between our ship and the way we were living, and what we

Studs Terkel And so something else of the 20th century. The polluted waters. Now, how did -- what were your findings here?

Thor Heyerdahl Well, we ran into severe pollution even before we hit the salt sea, when we were sailing down the Shatt-Al Arab. Having left the Tigris, we tied up on the banks one night when we discovered that suddenly we were sur-surrounded by white foam. It was just like being up in the Arctic drift ice, and when we checked, it happened to be they, they were cleaning out the chemicals of a, a paper mill, and this paper mill used to convert the reeds into paper pulp, that's the whole purpose. So we realized that if we're sitting in that, I mean the whole vessel would turn into pulp, so we really had to get going down the river as fast as we could. That was the first meeting, and later of course, we saw the usual pollution of oil, particularly bad in the area of Abadon where the fighting is now going on, where the Iran claims to have conquered the town. There the river was absolutely black, so it was disgusting to sail through it. In the, in the, in the Persian Gulf we were amazed that it wasn't worse than it was, that the reason probably is that the tankers usually let out the sludge before they enter the Hormuz Strait, because when we came through the Hormuz Strait we saw several tankers sending up really pitch black water astern. If they'd done it inside, they might have been discovered, because, of course, it's illegal today, and I must say that most ship owners and oil people today are realizing the problems, and that has improved greatly the last 10 years. But what has not improved is the pollution that we get from all the cities, all the detergents, all the insecticides from also from farm country. It all runs into either some sewer or some river, and it all empties into the ocean, and this is invisible pollution, which is the real danger in the long run, not the shipping.

Studs Terkel And, of course, what happens to the creatures of the sea. By you talk about adventures with them! The sharks, the dolphins, the turtles, the variety of sea creatures.

Thor Heyerdahl Yeah, well I've never seen so much marine life amazingly enough as on this trip. Particularly amazing because among marine biologists, the Indian Ocean is supposed to be almost a, a marine desert with very little marine life. I had this report from a United Nation vessel that been out looking for fish in the area, but when you float calmly on a reed ship, the fish will come and visit you, and we had them by the hundreds, and six or eight species all the time swimming under us or around us, so we could catch as much fish as we could care to eat, and what we couldn't eat we dried.

Studs Terkel By the way, you're describing the, the food you had, the various members of your crew cooking their native ethnic foods. Here again, we come to United Nations as far as

Thor Heyerdahl This was to me quite amazing. I mean, normally I have one man on board who is a good cook, and we depend on him and suddenly, unintentionally, I found that I had cooks from all over the world. The, the Japanese was a master cook, he had this small restaurant and knew how to prepare raw fish with all sorts of sauces and spices. And the young Muslim had brought with him all sorts of spices, and prepared the most incredibly good meals from flying fish, and then again, the Italian was really a professional cook. We got fine food out of him, and the, the German invented a certain fish soup that none of us had ever had for, before, by picking barnacles that grew on the side of the vessel and mixing it with chunks of, of fish swimming with us, and I could continue to enumerate

Studs Terkel Or was some caviar, too.

Thor Heyerdahl Well, that was the, the, the Russian of course. He had with him a lot of caviar, so whenever we had a birthday party or New Year's Eve, we really had a celebration.

Studs Terkel So I'm thinking about the crew. We have to come back to them again.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes.

Studs Terkel And their relationship one to the other

Thor Heyerdahl Yes.

Studs Terkel On this piece of Earth called a ship, the Tigris in this ocean, and we come back to it again. The lesson. Your late navigator, Erik Hesselberg on the ship Kon-Tiki once spoke of -- again, they were all Scandinavians, but different people of different ideas living on that raft for thousands of miles. We come back to that, that is the theme of almost all your works, the second theme, is it not in your trips?

Thor Heyerdahl Yes, it is. I must say that I am naturally as interested in the future as in the past, or much more to be quite frank, but I think, and I believe that most archaeologists have the same feeling, that most of us, we, we look at the time as something not existing, that the world is what it is today. But if you work with the past, you see that there is an alteration, a change. We're on the road and the -- we visualize that tomorrow is not going to be what it is today.

Studs Terkel As you were taking this trip, certain things were happening toward the end. You were going down the Arabian Gulf or the Persian Gulf. Which you finally call the Sumerian Gulf because they were arguing about titles, here we go again.

Studs Terkel Into the Gulf of Oman, touching Karachi, and now going down the Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, now here are places suddenly you cannot land. Now we come to contemporary politics and lunacy.

Thor Heyerdahl Yeah, this was a shock to all of us. We had been living like man 5000 years ago, and we felt that sailing in the reed ship, the formalities would not be very serious if we came to a country. But after nearly five months, when we're approaching the end of the voyage, we got on the little radio, amateur radio, messages all the time that "Be careful where, where you steer. Don't steer to port side because there is a war on." When we came to Somalia, what the ancient Egyptians called Punt, the Horn of Africa, we were told that they have just conquered one of the cities from the Ethiopians, and if you come inside a national territory, you will be fired at or interned, so you must steer better in the other direction. But again, don't steer too much there either, because then you get to south Yemen, and the national waters of south Yemen is forbidden territory, you'll be interned. And then we got calms and drifted towards the island of Socotra, and then we got desperate messages, even from the United Nations, that this is territory where nobody are allowed to go within sight or fly over, so do anything you can to avoid this island. So we sent messages that we cannot, there's no wind, and the current is pulling us towards the island, now we see the mountains and now we see in the end, after three days, we even saw houses, and it was a desperate situation with telegrams coming all the time of what would happen. And then finally we caught wind and sailed past, and in the end we had, really it was tight, top, rope-walking to get through the Gulf of Aden when we got a message that the only place that you can land is the tiny little new Republic of Djibouti, which was a mini-republic and the new president had just been to the United Nations to be accepted as a member. And he welcomed us, knowing that we had the United Nations flag. So fortunately, at this time we were really, had learned how to tack and how to navigate irrespective of wind, so we managed to hit that little port at the very entrance to the Red Sea. But once we were in there, we couldn't get out again. There was war on all sides, on the other side, we were between Eritreans and Ethiopians.

Studs Terkel Now we come to that moment don't we, this is the moment of a trip, and your 4000 miles ending five months navigating, finding out beginnings of Sumerian civilization that was far, far underrated, meeting anthropologists. And now we come to this moment in 1981. United Nations flag, 11 members of the crew, including yourself, of all different societies, and now you see lunacy. Madness.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes, to us it was, it was really sad. We hardly believed our own eyes. All we saw were warplanes overhead and battleships and warnings about war going on, we heard the gunfire, and when we came into the port, we saw all the poor refugees, women with children and wounded. And it was a nightmare. We of course could end the expedition here with no problem, we had planned to go four more days to Massawa, which was nothing after five months trip, we had now been more than five months on board. So we could fly out but, but what about the, the vessel? There was nowhere to take the, the, the vessel, and leaving it in the polluted water of the port we knew that within a month, or maybe a little more, the terribly dirty water of this port, it happened to be the main port of the French Indian Ocean navy. The vessel would disintegrate, ropes and all, so what we decided, we wanted, there had to be an end to this vessel, but we wanted a, a proud end, so we pulled it out of the harbor, took down the United Nations flag and set it afire sails up. It was a very sad moment for all of us. But all the 11 men agreed as we signed the telegram, which was sent to Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, who had given us permission to sail under United Nations flag, we told him that we had lived together in peace and harmony, but that we did this because we wanted to burn the vessel as

Studs Terkel You burned the vessel. You know, I'm thinking about the idea. You -- the, the deed. You burned the vessel, now here are the people fighting. And perhaps you should read your message to Waldheim, and I, I'm moved. I just turned to a page accidentally, and we -- it says, "Suddenly nowhere to sail any direction." This is the writing of Thor Heyerdahl. "Scientifically it didn't matter a bit. We were not allowed to add another five days to experiment gone on for five months. What hurt all of us, we'd come back to our own world, our own contemporaries and met again the result of 20 centuries of progress since the time of Christ, the peace-loving moralist whose birth marks our own zero year, and here around us on all sides, wonderful people who were taught to kill each other by our own experts and we helped to do so by the most advanced methods man had invented at the end of five millennia of known history." I'm thinking

Thor Heyerdahl It is a sad fact.

Studs Terkel Suppose you read your message to Secretary General of United Nations Kurt Waldheim.

Thor Heyerdahl Well, what I have here in the end of my book is the telegram we all signed and sent to him. "As the multinational crew of the experimental reed ship Tigris brings the test voyage to its conclusion today, we are all grateful to the Secretary General for the permission to sail under United Nations flag. And we are proud to report that the double objectives of the expedition have been achieved to our complete satisfaction. Ours has been a voyage into the past to study the qualities of a prehistoric type of vessel built after ancient Sumerian principles, but it has also been a voyage into the future to demonstrate that no space is to be restricted for peaceful coexistence of men who work for common survival. We are 11 men from countries governed by different political systems, and we have sailed together on a small raft ship of tender reeds and rope a distance of over 6000 kilometers from the Republic of Iraq by way of the Emirate of Bahrain, the Sultanate of Oman and the Republic of Pakistan to the recently born African nation of Djibouti. We are able to report that in spite of different political views, we have lived and struggled together in perfect understanding and friendship, shoulder to shoulder in cramped quarters during calms and storms, always according to the ideals of the United Nations: cooperation for joint survival. When we embarked last November on the reed ship Tigris, we knew we would sink or survive together, and this knowledge united us in friendship. When we now in April dis-disperse to our respective homelands, we sincerely respect and feel sympathy for each other's nation, and our joint message is not directed to any one country but to modern man everywhere. We have shown that the ancient people of Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and Egypt could have built man's earliest civilizations through the benefit of mutual contact with the primitive vessels at their disposal 5000 years ago. Culture arose through intelligent and profitable exchange of thoughts and products. Today we burn our proud ship with sails up and rigging and vessel in perfect shape to protest against the inhuman elements in the world of 1978 to which we have come back as we reach land from the open sea. We are forced to stop at the entrance to the Red Sea, surrounded by military airplanes and warships from the world's most civilized and developed nations. We are denied permission by friendly governments for security reasons to land anywhere but in the tiny and still neutral republic of Djibouti because elsewhere around us brothers and neighbors are engaged in homicide, with means made available to them by those who lead humanity on our joint road into the third millennium. To the innocent masses in all industrialized countries we direct our appeal, we must wake up to the insane reality of our time which to all of us, has been reduced to mere unpleasant headlines in the news. We are all irresponsible unless we demand from the responsible decision-makers that modern armaments must no longer be made available to the people whose former battleaxes and swords our ancestors condemned. Our planet is bigger than the reed bundles that have carried us across the seas. And yet small enough to run the same risks unless those of us still alive open our eyes and minds to the desperate need of intelligent collaboration to save ourselves and our common civilization from what we are about to convert into a sinking ship. The Republic of Djibouti, third of April 1978."

Studs Terkel Nineteen seventy-eight. Your message, that of you and your crew to Kurt Waldheim is, of course, is what the trip is about too, isn't it?

Thor Heyerdahl To us, it was about that really.

Studs Terkel You were discovering a civilization of the past, which, by the way, you implied in your message, your findings was based upon some cooperation. It was a highly advanced civilization you discovered in the various stops.

Thor Heyerdahl This is how civilization began. Man traded in a friendly way, one nation with the order to the benefit of all.

Studs Terkel That's the point, isn't it? In, in the various stops you made, you found highly developed engineering cities, sanitation systems. But it was -- there was a cooperative nature to it.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes, it was quite clear that there was an inspiration and through cooperation. We found it right from the moment we left Iraq and came to the island of Bahrain, which was the legendary Dilmun of the ancient Sumerians, where Dr. Geoffrey Bibby had excavated and [hid?] the [unintelligible] port city from that same early period 45000 years ago below the sand.

Studs Terkel You mentioned Dr. Geof-Geoffrey Bibby, the archaeo - the archaeologist, this curious, tell me how you go on these adventures? He was reviewing your book in The New York Times Sunday Book Review, The Ra Expedition, and he said, "To Thor Heyerdahl, why not another adventure? I offer you a real challenge, the trip from the Euphrates/Tigris confluence down the Arabian Gulf and, and through it to the Indian Ocean to see how civilization came into being." And it was the book review of his that set you off on this.

Thor Heyerdahl Well, indirectly. I mean, at the moment I read his review, I never thought of doing it. But as my research continued, I got more and more interested in the fact that these early Sumerian ships must have been seaworthy. And when we started, Dr. Geoffrey Bibby actually flew from Europe down to Bahrain to be there to see a reed ship coming in, because he, of course, had discovered that there must have been seaway contact because an island, you don't swim out to build the city like the one he had discovered. And he had discovered a large number of Sumerian artifacts on the island, also artifacts from the Indus Valley, so he was convinced beforehand that there had been contact between these early civilizations, but the problem was how, because they had no wooden ships in that period.

Studs Terkel Another asp-- discovery, of course. How little, how little we really know of past. Even science itself gets bewildered, as you, you showed.

Thor Heyerdahl I think that we, we have to be very careful to believe that we know the answers. We know very, very little. And I think that when we realize that just a couple of decades ago, we thought that man had been on this planet for being maybe maximum 100 to 200,000 years. Suddenly we wrong that -- learned that this is all wrong. Man has been around for more than two million years. So what about civilization? We certainly do not know the real beginning yet. It starts too abruptly about 3000 B.C. in three different places so close together that [only?] natural sailing a few weeks with a reed ship and they could be inspired one from the other.

Studs Terkel You remember how we opened this program? Dr. Heyerdahl, we opened the program, you were reading something 10 years ago, it was 1971 on this program about the Ra adventure and facing, man facing the challenge. Since 10 years ago, the nuclear arms race has quantum jumped more than ever. So here we are again now.

Thor Heyerdahl Yes, I think that the only bright the development that I can see is that we all, all nations start to see the need of international collaboration to avoid global pollution. Maybe this disaster, which would have come unless we really start to do something about it, maybe that threat, I have seen that it's always a common enemy that will bring people together, nations together. Well, here for once, all nations have one common enemy: ocean pollution, atmospheric pollution.

Studs Terkel Destruction.

Thor Heyerdahl Nuclear, nuclear destruction.

Studs Terkel I'm thinking, I come -- we come back to that moment when that guy got up an hour earlier, earlier than he should have, to relieve the other man on the watch.

Thor Heyerdahl This happened more than once on

Studs Terkel So there it is again. The common humanity and common need. Perhaps to end the hour, read the last paragraph, you decided to burn the ship. You and your colleagues. Just the last passage of the book. The Tigris Expedition, Thor Heyerdahl my guest, Doubleday the publishers.

Thor Heyerdahl I ended my book with these words. "We lined up ashore and none of us could say much. 'Take off your hats,' I said at last as the flames licked out of the main cabin door. The sail caught fire in a rain of sparks, accompanied by sharp shot-like reports of splitting bamboo and the crackling of burning reeds. Nobody else spoke, and I barely heard myself mumble, 'She was a fine ship.'"

Studs Terkel "She was a fine ship."

Studs Terkel She was indeed. And this world, I suppose, could be. Some would say, "Might have been." Dr. Heyerdahl, Thor Heyerdahl. Thank you very much indeed.