Poets and Poetry as Agents of Change, 1957-1977 by Joseph Coulson

Listening to Studs Terkel interview a poet is to realize that the power and music of poetry occupy a special place in the range of Terkel’s intellectual and emotional interests. He listens with great relish as poets read their poems, occasionally joining in the recitation, and reacts to the work with a rare combination of wonder and insight. Importantly, he draws out the poet with an easy grace so that listeners can better understand the relationship between the artist’s imagination, the craft of poetry, and the poet’s historical moment.

This selection of interviews spans a twenty-year period that signifies a monumental shift in the social and political content of North American poetry, focusing in large part on poets who did much of their work outside the academy. Terkel examines both the poetry and the lives of the poets, exploring with each artist the boundaries of poetic expression and shedding light on the poet’s role as observer, social critic, and agent of change.

Starting in the late 1950’s, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, poet and proprietor of City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, takes up the question of Beat poetry, its origin and point of view. Ferlinghetti, having published Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and having been absolved of obscenity charges by the California Supreme Court, spars with Terkel over the question of literary “point of view,” a concept that the Beat poets consider hopelessly “hung up.” The Beat writer rejects “timeclock civilization,” eschews classification, and is suspicious, as Groucho Marx would say, of any institution that would have a Beat writer as a member.

The Beat theme continues in a 1960 interview with Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky. The conversation is an exercise in creative anarchy with Terkel trying to referee the exchange. Something rarely heard then or now is Terkel making a lengthy aside to the radio audience while the poets continue to talk with each other, an attempt to offer a play-by-play that would be accessible to those unfamiliar with the Beat generation’s irreverence for the context of an interview, for literary conversation, and for both the artistic and political establishment.

Leaving the Beat poets, Terkel’s approach with John Logan in 1960 is measured and comfortable, and the music of Logan’s language and voice creates a leitmotif that underscores the entire interview. Logan speaks of poetry in a deeply spiritual sense, with the poet acting as a “secular priest” and with the poem itself offering the reader a chance for “secular grace.” Terkel’s interaction with Logan teases out the tension between the profound musicality of the language and the poet’s turmoil roiling just below the surface of the poem.

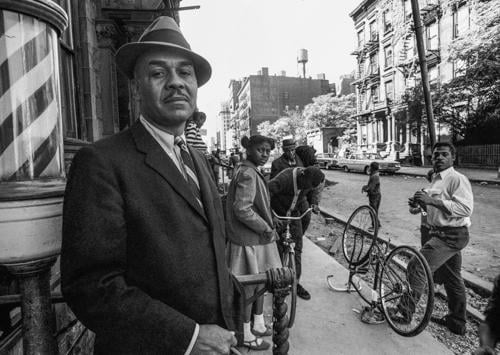

In 1967, Terkel sits down with Gwendolyn Brooks to talk about her new long poem, In the Mecca. The Mecca or the Mecca Flats, an enormous structure built as a hotel for the 1893 World’s Fair but later serving as a rundown apartment building in Chicago’s Bronzeville, serves as a broad canvas for Brooks’s growing political activism which, according to critic George E. Kent, “managed to bridge the gap between the academic poets of her generation in the 1940s and the young black militant writers of the 1960s.” Brooks and Terkel, both enthusiasts and clear-eyed realists for Chicago and its history, probe and reveal poetry’s power to evoke a vivid sense of place, a neglected community, and a dignified record of the poor.

The sublime poet Denise Levertov shares the microphone with activist George Matthei, discussing her role and the role of poetry in the anti-war movement of 1969. Matthei, having been arrested for “draft refusal,” takes up the “revolution of the personal,” which draws on the philosophies of Thoreau and Gandhi. Terkel’s questions lead to profound meditations from both Levertov and Matthei on environmental atrocities, the machinery of oppression, the duty of civil disobedience, and the pragmatic expression of love in the face of hatred and anger. This interview, made at the zenith of 1960’s upheaval, stands as a political and philosophical record of the period.

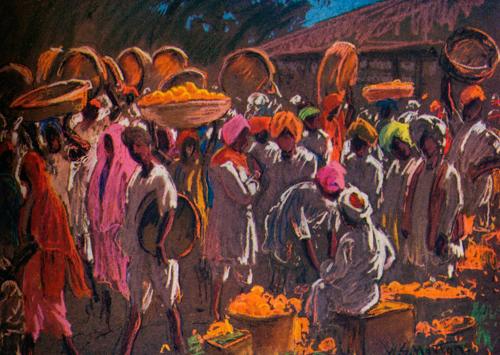

With Maya Angelou in 1970, Terkel returns to the poetics of place, but this time the setting is Stamps, Arkansas and the “wordly music” of Angelou’s autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Terkel is particularly drawn to the portraits of working people that populate this hypnotizing prose poem. In the same way that Gwendolyn Brooks speaks of the Mecca, Angelou speaks of Mrs. Henderson’s store as a lynchpin of her childhood community, a place of hope and broken dreams. Terkel’s questions, reactions, and laughter convey his empathy for those trapped by inequality and struggling against injustice.

Although recorded in 1975, Terkel’s interview with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs returns to 1968 and the chaos of the Democratic Convention in Chicago. Ginsberg and Burroughs, traveling in the company of French novelist and poet Jean Genet, find themselves the victims of teargas, and they stumble into the lobby of the Midland Hotel to seek shelter from the noxious fumes. Terkel and British journalist James Cameron provide the initial context in a clip from a 1968 interview, and then reading from published poems and essays, Ginsberg and Burroughs remember and reflect upon the Democratic Convention as a pivotal moment in culture and politics. Here we have poetry and prose as reportage, and the description of teargas canisters flying across the shadow of a rough-hewn cross lifted in the park by protesters is alone worth the listen.

Margaret Atwood came to Chicago in 1976, and though it would be nine years before she published The Handmaid’s Tale, her political acumen is prescient and her intellectual scope formidable as she and Terkel discuss a broad range of political issues, including Canadian-American relations. Atwood speaks of Canada consciously distancing itself from the U.S. after Vietnam, and her comments about “winning” in America foreshadow the Trumpian ethos and the religious and capitalistic dictum of “conquest toward everything.” Later in the interview, Terkel raises the figure of Melville and Atwood speaks of her sympathy for Moby Dick in the wake of Ahab’s insane obsession, and she observes that Melville placed “representatives of every part of American society” on the Pequod, Ahab’s doomed ship.

This group of nine interviews ends in 1977 with Detroit poet Philip Levine, the poet of the working class and the champion of the working poor. Terkel and Levine speak to each other as brothers, kindred spirits who understand the value of commemorating the commonplace and of preserving the memory of lost neighborhoods, communities, and cities despite the onslaught of time. Terkel characterizes Levine as a different kind of writer, “an urban poet” in love with the city, both its grit and its beauty. Levine and Terkel, using poetry and music respectively, speak of the importance of art for the person on the street, and the individual’s journey to a place where he or she will one day believe, “I am worthy of poetry. I am worthy of art.”