Jonathan Wordsworth discusses William Wordsworth

BROADCAST: Oct. 4, 1982 | DURATION: 00:54:39

Synopsis

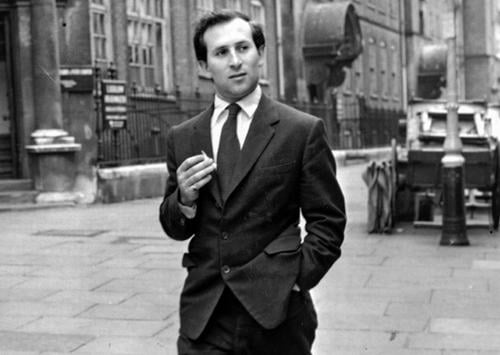

Terkel interviews Jonathan Wordsworth about his great-great uncle William Wordsworth.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel [buzzing sound] I forget the teacher's name, but it was English Literature I, and it was Crane Junior College, and we came to Wordsworth, and she, he said the Romantic period of, in British literature and then were the poems. But there was more to Wordsworth than that, he lived at a certain time, a time of tremendous turmoil, change, revolutions, and what happened to him from his young manhood to his old age, Wordsworth himself. Did he change and to what extent and the influence of Coleridge on his life, and I'm delighted to have as guest his descendant. I would say, if I said, great-great-great, I'm missing a great somewhere, am I not?

Jonathan Wordsworth No, no, I think that's about right.

Studs Terkel That's about right. Jonathan Wordsworth, who teaches at Cambridge, visiting right now--

Jonathan Wordsworth No, that's quite wrong. I teach at Oxford.

Studs Terkel You teach at Oxford.

Jonathan Wordsworth You can't go confusing Cambridge and Oxford on our side of the Atlantic, you may do it over here.

Studs Terkel Yeah, but that's pretty bad.

Jonathan Wordsworth That's pretty bad.

Studs Terkel Oxford.

Jonathan Wordsworth Wordsworth was at Cambridge. I am at Oxford.

Studs Terkel Oh, that's it. That's -- now we got it straight. And your thoughts, you know, your own studies of your romantic and revolutionary ancestor and visionary, William Wordsworth. In a moment the program.

Cedric Hardwicke "Earth has not anything to show more fair: Dull would he be of soul who could pass by a sight so touching in its majesty: This City now doth, like a garment, wear the beauty of the morning; silent, bare, ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie open unto the fields, and to the sky; all bright and glittering in the smokeless air. Never did sun more beautifully steep in his first splendour, valley, rock or hill; Ne'er saw I, never felt a calm so deep! The river glideth at his own sweet will: Dear God! The very houses seem asleep; and all that mighty heart is lying still!"

Studs Terkel Cedric Hardwicke reading Wordsworth. This period, 1802 this was composed. Now, that was--well, what was the situation at the time?

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, it was a slightly complicated situation. Wordsworth was writing at the top of his powers. This is absolutely prime Wordsworth. He was in London and he's, he was either just on his way to Paris--sorry, not Paris, to France--or on his way back. The person he was seeing there was his girlfriend of the French Revolutionary period, Annette Vallon, by whom he had a child, Caroline, who was baptized in Orleans Cathedral as Anne Caroline Wordsworth in December 1792, a very historic moment. And now 10 years later, he was seeing her mother for the first time.

Studs Terkel Oh, this is oh, he was about 30--

Jonathan Wordsworth He was 32.

Studs Terkel Two. Now, why was he go---aside from the romantic involvement.

Jonathan Wordsworth You mustn't misuse this word 'romantic,'

Studs Terkel Yeah, well small 'R.'

Jonathan Wordsworth Small

Studs Terkel In this case. Well why, Paris or France played another role in his life as well, didn't it, France at the time?

Jonathan Wordsworth France for Wordsworth and his contemporaries was the France of the revolution in which all their hopes were vested. They really hoped that a complete change would come over the world, that there would be universal happiness. They believed it. And it was you who set it off, it was the American Revolution, not the French. The French followed suit.

Studs Terkel So it's funny. The American Revolution against Wordsworth's own country, that is, you know there were seeking independence. So the young, the young poets, the young creative spirits were very excited about.

Jonathan Wordsworth But not only the young. There was a great feeling in England that the American Revolution had started something and I think of a very distinguished elderly figure, a man called Richard Price, who was a dissenter and one of the most distinguished intellectual men of his day. He got up in 1785, four years before the French Revolution, a couple of years after you'd achieved your independence, and he said very solemnly, very seriously, he was a dissenting minister, that next to the introduction of Christianity, the American Revolution would prove the most important event in the introduction of this final period of human happiness.

Studs Terkel You know, it's interesting. This was going on in England at the time that George III was sending troops here. So there was a strong dissent from British authority then at this

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, this is slightly later, after all. The, the war had ended.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Jonathan Wordsworth But yes, there was a dissent from

Studs Terkel So now the French Revolution was the center.

Jonathan Wordsworth The French Revolution seemed to people to follow naturally after the American and to show that one country after another was choosing freedom and was going to give freedom to everybody, and it was assumed, and Wordsworth was one of many thousands who assumed it, that the French Revolution would be followed by the British revolution.

Studs Terkel Well, how, how--could, could you, since Wordsworth is part of your world, your intellectual world, what did Wordsworth, did he in letters, correspondence, poems, were there thoughts of how it would happen in, in Britain?

Jonathan Wordsworth It was assumed that it would happen in Britain very much as it had happened in France. And I would have to go back a little to talk about France to answer your question I think. The French Revolution gets very bad press because of Robespierre and The Terror and the guillotine and rivers of blood. That's not how it was. The French Revolution started with the fall of the Bastille on the fourteenth of July, 1789, which was a symbolic event of violence because it, the Bastille was a great symbol of tyranny and oppression. But it wasn't a fact. There were very, very few people in there, and there were very, very few casualties that day. What was got rid of was a symbol, and for the next three years, until August 1792, the French Revolution was very peaceable. It was led by very constitutional people who had, they--in a way, they were rather academic. They discussed very seriously how they could reform the constitution. They were working within the monarchy, they were asking Louis XVI to be a constitutional monarch and to give a fair deal. And it was not until he was effectively deposed in August '92 that things started to change. Then there were the September massacres, which Wordsworth writes marvelously about. He was in Paris just after this. He actually saw the fires in the, in the center of Paris, the signs of the fires where they burnt the bodies. He was in Paris just a month afterwards.

Studs Terkel Now, this 'Terror' that took--Wordsworth was describing, this Terror was the White or Red Terror? This was, this was, this was the Robespierre time?

Jonathan Wordsworth Robespierre was not yet there, really, and Robespierre was coming to power. It was Danton who was in power at this moment. There was a, a big challenge to, to Robespierre's power at this period by Louvet and Wordsworth talks about this, but Robespierre rode it out and, and actually did achieve supreme power.

Studs Terkel So was that when the young British poet Wordsworth was beginning to become disenchanted?

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh no! No, no, they didn't. They were very, very faithful. Wordsworth and all the British radicals were very faithful to the ideal of the Revolution for quite a long time. What happened was that Wordsworth had been in France from the end of 1791 up to about November '92, when in fact a lot of the British people in Paris were then interned, and the party that they sympathized with, Girondins, were in fact losing their grip, and--

Studs Terkel Jacobins.

Jonathan Wordsworth And the Jacobins were taking over, and it was the Jacobin takeover that led to the execution of Louis XVI in January '93, by which time Wordsworth was back in England having left behind the daughter whom he'd never see, who had been born and baptized just at the end of November, beginning of December.

Studs Terkel He still had that vision, though.

Jonathan Wordsworth He had that vision and he wrote a very moving passionate piece of prose at this period which people don't know, called the, which was in the form of a letter to the Bishop of Llandaff. And Llandaff had come out in a, a very creepy way expressing his horror at the death of the king and taking a very, very soapy conservative view about the wonders of the British Constitution and how marvelous it was that the law was on the side of the poor as well as the rich, and Wordsworth wrote a very ironic passionate letter congratulating him on his, you know, his relationship with the law, pointing out that it was not everybody's. And at that moment he was, I think, very involved in politics. Indeed, it was the center of his life.

Studs Terkel Is there a poem of that period that perhaps you could find?

Jonathan Wordsworth No, I think it will be very difficult to find. There are, there are early poems, but the--

Studs Terkel Here, here's one that's very interesting. Upton Sinclair, the great muckraker turn of the century, the American muckraker who challenged corporate powers and all, has an anthology called Cry for Justice, and it's revolutionary poems and poems of the underdog throughout history. He's got a Wordsworth poem, the same year as the one that Hardwicke read, 1802--are you, could you read sight reading? You a good sight-reader?

Jonathan Wordsworth Depends what we have. Yes. How interesting. It's not a poem I know well, I have to confess.

Studs Terkel Well, it's sight-reading.

Jonathan Wordsworth Wordsworth wrote rather a lot and it's rather hard to be confronted with poems one ought to know better than one does. "O friend! I know not which way I must look for comfort, being, as I am, opprest, to think that now our life is only drest for show; mean handy-work of craftsman, cook, or groom! We must run glittering like a brook in the open sunshine, or we are unblest: the wealthiest man among us is the best: No grandeur now in nature or in book delights us. Rapine, avarice, expense, This is idolatry; and these we adore: Plain living and high thinking are no more: The homely beauty of the good old cause is gone; our peace, our fearful innocence, and pure religion breathing household laws." Very moving.

Studs Terkel It is. Now that was

Jonathan Wordsworth Not the famous Wordsworth poem,

Studs Terkel But that's the same period as the other. The one--so he still had the fervour and that feeling.

Jonathan Wordsworth I think he always kept it.

Studs Terkel You think he always kept

Jonathan Wordsworth He's very famous as a turncoat, partly because Shelley brands him as one, and of course by the time Shelley came along he was the next generation of great Romantics. Shelley was experiencing the full youthful fervour at a moment when Wordsworth was older and, and perhaps a sadder man. He'd seen a lot of disappointed hope.

Studs Terkel So Wordsworth now getting--that's a, this is almost one of these eternal crises. It happens throughout. The younger radical comes along, poet, and the older guy's a bit tired now

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes,

Studs Terkel And the younger one attacks the older as being a compromiser.

Jonathan Wordsworth I'm afraid that's right, yes.

Studs Terkel But Wordsworth you feel that he always kept to his vision.

Jonathan Wordsworth Wordsworth's vision was not a purely political vision. And that's why I say he always kept to it. What he kept to was the ideal of the greatness of the individual human being, the greatness of human aspiration. What a man can achieve, and he saw this early on in political terms. All his contemporaries did. As he moved away from this, he saw it in terms that talk about the individual consciousness in a way that I think has a great deal to say to us today. I think this is why Wordsworth is, is the founder of Romanticism in, in the broadest sense, a sense in which we are all romantics. Certainly should be.

Studs Terkel Yeah, boy, romantic in the best sense. Why is it called the Romantic period? That, that period from the French Revolution to what, 1830s, around early '30s?

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes. I don't think there's a good reason for using the name. But if we have it, then we must define, define it very broadly. It, it's got nothing to do with amorous romanticism, eroticism. In fact, the, the Romantics were curiously not a very--not, they didn't write much love poetry, for instance. Nothing like as much as earlier periods in English literature, the metaphysical.

Studs Terkel Now we come to--before, well, was it his meeting with Coleridge had altered his way of thinking, too? Now that's the great friendship, is it not, Coleridge and Wordsworth?

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, that's the great friendship, but it was Wordsworth's second great friendship, not his first. His first, you see, was in France, with this patriot Michel Beaupuy who, who turned Wordsworth into a Republican and a political figure, and his influence, I think, was very, very dominant. And then Coleridge comes along as the second great influence in 1797, five years later.

Studs Terkel You know, it's funny--during that period, the political period, there's a, a piece here by Carl Woodring of Columbia that you know on Wordsworth, and there's this reference from the poem An Evening Walk, it's about that period we were just talking about, 1802, 1801, and he says, "We watched the approach," he writing a Wordsworth poem, "of a burdened mother whose soldier fell on" quotes "on Bunker's charnel hill."

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes, this is a much earlier

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Jonathan Wordsworth And this is, this is a poem that he's actually writing before the French Revolution.

Studs Terkel Yeah, well, this is about the American Revolution. Fell on "Bunker's charnel," so he is opposing the, the British attempt to put down the American Revolution. So it's the about that young British soldier.

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes.

Studs Terkel Who was sent over.

Jonathan Wordsworth Wordsworth's sympathy is, is entirely with the, the widowed mother, her children, and the, the soldier who perishes in an unjust war.

Studs Terkel Yeah. So then came his getting a little older, not changing, getting a little older and then he saw the broader aspect of freedom, is that--now, nat--I suppose the word 'nature' comes into in--with a capital 'N' comes into his writings now more and more, doesn't it?

Jonathan Wordsworth I think nature's always been there. It depends what you mean by nature. We started with a poem composed on Westminster Bridge which is after all bang in the middle of the City of London, and he is talking about the beauty of the City of London, and he is saying that here, amid these buildings, he can feel, he can respond, as deeply to the city as he responds to the valley, rock or hill of his native Cumberland. And this is right. Wordsworth is sometimes thought of as, as against cities. He's not. He's against the city way of life. But those who carry into the city the wonderment, the responsiveness, the ability to, to lose the selfishness and the preoccupation of city life, they have him on their side.

Studs Terkel So he wasn't as being against the city, as of course at this time the Industrial Revolution was just getting underway, and so

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, it was well underway, yes.

Studs Terkel Yeah but something was happening now to people in the city. I suppose it was the big move to the city.

Jonathan Wordsworth It was a very horrifying period and a, a period of very great poverty and I think Wordsworth felt that if you moved into the city you lost your roots, you, you accepted a sort of impoverishment of your emotional life as well as everything else, and the people who were moving into the city had been brought up in villages where they were parts of a seasonal way of life, which he believed to be very valuable, which I believe to be very valuable.

Studs Terkel So in a way what he was attacking was not different from what William Blake was attacking, too. The "dark, Satanic mills."

Jonathan Wordsworth They're, they were, no, Blake was just a little older than Wordsworth.

Studs Terkel Oh, I know. I mean--

Jonathan Wordsworth They're, they're exactly the same.

Studs Terkel Yeah. I meant his, his vision--

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes.

Studs Terkel Was not removed from Blake's

Jonathan Wordsworth N. Blake had--Blake's vision was, you know, more way out, but it was, it was the same, yes.

Studs Terkel They both were attacking the "dark, Satanic mills."

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes. Blake makes his famous comment that if the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite. So all you had to do for Blake is to see straight and then you will perceive that everything is part of a total harmony and infinity. Wordsworth is very close, and both, both of them are talking about the possibility of the imagination as a way of losing one's selfish concern.

Studs Terkel Well I say that's amazing that both, that we, usually, at least I, the layman, or the guy who just has a cursory knowledge at best, doesn't associate Blake and Wordsworth, yet there's a remarkable affinity.

Jonathan Wordsworth They're very, very close, yes. And Shelley, too.

Studs Terkel And Shelley, too, even though he attacked Wordsworth.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, he admired him. One attacks one's father, you know. He admired him. He, he responded to him, and that was a very close relationship, even if there was hostility in it.

Studs Terkel Why don't we, why didn't you try--of course, you read, that sight reading was beautiful, you did of that poem you hadn't seen before, how about Jonathan Wordsworth reading another poem of William Wordsworth and then we'll take a pause and ask you about his friendship with Coleridge and how that affected his writings and view.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, I have in front of me on the page The Solitary Reaper. I don't know that I'd wish to make any very political points about it, it just seems to me to be a compellingly beautiful poem. This is a year or two later, 1805. "Behold her, single in the field, yon solitary Highland Lass! Reaping and singing by herself; Stop here, or gently pass! Alone she cuts and binds the grain, and sings a melancholy strain; O listen! For the Vale profound is overflowing with the sound. No Nightingale did ever chaunt more welcome notes to weary bands of travellers in some shady haunt, among Arabian sands: A voice so thrilling ne'er was heard in spring-time from the Cuckoo-bird, breaking the silence of the seas among the farthest Hebrides. Will no one tell me what she sings?--Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow for old, unhappy far-off things, and battles long ago: Or is it some more humble lay, Familiar matter of to-day? Some natural sorrow, loss, or pain, that has been, and may be again? Whate'er the theme, the Maiden sang as if her song could have no ending; I saw her singing at her work, and o'er the sickle bending;--I listened, motionless and still; and, as I mounted up the hill, the music in my heart I bore, long after it was heard no more."

Studs Terkel So beautiful. And, again, as I listened to you read, I thought he's, he's celebrating the anonymous, the commonplace, the non-celebrated.

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes. And she's just an ordinary girl doing her job, which is to cut this corn and to bind the sheaves. This is part of an unending, a seemingly quite permanent way of life that has a complete brightness. She's doing nothing elaborate, nothing to do with the selfish pursuits of the great cities or the Industrial Revolution. She will be there always just doing that.

Studs Terkel So he never abandoned this vision, this view, this way of seeing things.

Jonathan Wordsworth No, I think the last lines, "the music in my heart I bore long after it was heard no more." And this is, this is the greatness of his poetry. He internalizes this vision, gives it the importance for the rest of us that it had momentarily for him.

Studs Terkel Jonathan Wordsworth is my guest at the moment traveling through the United States and, and lecturing during his stay at Chicago at the University of Illinois, Circle Campus, and reading the poetry of his, of his ancestor. And more about--because that's one of the friendships always fascinated me, again not -- knowing so little about it, about Coleridge and Wordsworth and their vision and what happened to each of them as they grew older. [pause in recording] Resuming with Jonathan Wordsworth and the subject William Wordsworth. And somehow we can't do a program about William Wordsworth without evocations of childhood visions, and so the one I remember of course from Literature One is "My heart leaps up when I behold a rainbow in the sky," and so let's hear Cedric Hardwicke again and, and the reading of that. And then you take off from there.

Cedric Hardwicke "My heart leaps up when I behold a rainbow in the sky: So was it when my life began; So is it now I am a man; So be it when I shall grow old, or let me die! The Child is father of the Man; and I could wish my days to be bound each to each by natural piety."

Studs Terkel Or the child is father of the man, my heart leaps up, so I suppose here you have a sense of wonder, don't you, never to lose that childhood sense of wonder.

Jonathan Wordsworth This is what was most precious to Wordsworth, yes. I think he felt that the adult vision was very different from the child's. It's not that the adult can have the child's vision. It has something that is older, wiser, sadder. But it must retain the wonderment, and childhood was precious to Wordsworth partly for this quality, the quality which Blake regards as innocence. But it was precious to him also because he thought it was the foundation of his own adult consciousness, and so he could take into account the odder, stranger, frightened, sometimes very guilt-laden aspects of childhood, which we all of us know to be part of it, and which after all, modern psychology would agree to be extremely important. He is the first poet to reckon with this.

Studs Terkel Only the first poet to, to face that head-on?

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, yes. Oh yes. Well, Shakespeare was amazing in his anticipation of this, and we see the relationship of Hamlet and his mother, for instance, which obviously fascinated Freud for very good reasons, and it is extraordinary the way Shakespeare can tell us about human relationship. But Wordsworth is the first to talk about the foundations of an individual consciousness in a way that really makes sense to us now.

Studs Terkel But also not innocence, not--you know, innocence not as ignorance of what is happening, but that sense of innocence and wonder.

Jonathan Wordsworth That's

Studs Terkel That is constant astonishment.

Jonathan Wordsworth That's right. It's a higher innocence. Ignorance is of no value to anyone. Innocence sees things for what they are without making--attempting to make them more than they are, or, or, or seeing them for some personal selfish motive.

Studs Terkel And so that never lost, though there's the question of age it comes into it, too, later on, so Intimations of Immortality came when? When were the--how long a lapse was it between these two?

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, Intimations of Immortality is a poem written in, in over two years, he wrote it in two pieces, and the first bit is simply the next day after the rainbow. He wrote, "My heart leaps up when I behold a rainbow in the sky" one day, and the next morning at breakfast he wrote, "There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, the earth, and every common sight, to me did seem apparelled in celestial light, the glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore;--Turn wheresoe'er I may, by night or day. The things which I have seen I now can see no more." So that his assertion on the one day was followed on the very next by this alternative mood in which he felt bound to say, to say out loud that "the things which I have seen I now can see no more." And this is the greatness of his poetry. He faces fact, he faces change within the conscious self and within the unconscious processes that are the stuff of his poetry.

Studs Terkel Yeah. So, you know, it's funny, in one of the lectures on Wordsworth, one of your colleagues, it was Kroeber or, or, or this guy, Woodring, they -- Ruskin speaks of Turner, but it could well have been Wordsworth. Of course Turner was being rapped by some critics, and Ruskin was defending him because he sees things, a painter sees things as they appear to be to him over and beyond, or at what they should be to others. Others see it. And so he, Wordsworth, too, had that quality.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, if you remember, Turner actually makes the comment at one stage that he doesn't wish to paint a landscape, he wishes to paint a landscape plus a man's soul, and that's right. That is Wordsworth. Wordsworth is no nature poet if you think he's going to describe the landscape, because he isn't. You look, you look in vain in Wordsworth's poetry for descriptions of landscape. But the response to the natural world, the external world in which the individual lives is the, the stuff of his poetry.

Studs Terkel So over and beyond a description, of course, of flowers and grass and sky. It's, it's what it means to the person.

Jonathan Wordsworth They, they are given their life in Romantic poetry by the response.

Studs Terkel Would it be accurate to say, then, Wordsworth is to poetry what Turner is to painting? To some extent?

Jonathan Wordsworth I think yes, yes I think so. But of course Wordsworth is--yes, I think that's right. Wordworth is really underway slightly earlier. I think the poets are, are slightly ahead of,of the great painters Turner, Constable.

Studs Terkel So what was happening then? We speak of the 40 years of Romantic poetry. And you said something before we went on the air, that something happened now to British literature with the Victorian period coming your way, that wasn't poetry anymore, it was the dominant way of seeing.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, I suppose that's--I think that's right, myself. People would disagree with me very violently. I feel myself that the great Victorian poets, Tennyson, Arnold, Browning, though they are marvelous writers, are writing in a form that has become less dominant. I think poetry was right at the center during the Romantic period. We have revolution, we have poetry, prose is, is further out from,

Studs Terkel So now the novel was taking

Jonathan Wordsworth The novel seems to take over in the Victorian period, and Dickens is, is a figure that has the grandeur. He has the imaginative power. Dickens is a great poet, a great user of language as, as poetry, and of course also a great interpreter of what he sees outside. I think he is the big man of this next period, not Tennyson.

Studs Terkel So it was the novel.

Jonathan Wordsworth I think the novel really

Studs Terkel You think the Industrial Revolution had a lot to do with that, too? The fact that here was something not, maybe not made for a poetic form but for something not descriptive in the, in the literal sense, but something that would dig deeper into the daily lives of people? I don't know. The Industrial Revolution itself and the, the mills and the factory life and the crowded--

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, I think that's right. But I think the, the great poetry of Wordsworth and Blake can protest against this in a way that is very moving, very passionate, but perhaps, perhaps the novel form is, is needed to make the larger statements that Dickens goes on to make.

Studs Terkel So now we come to Wordsworth. He lived, how long, 'til when?

Jonathan Wordsworth He lived 'til 1850. He was a man of 80.

Studs Terkel Eighty. It was 1850. So what was happening now? Now friendships, influences on his life aside from events in the world. Personal influences. Now we come to Coleridge.

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes. Wordsworth and Coleridge meet, well, they'd, they'd met once twice before, but effectively they come together in the summer of 1797. Coleridge is the better-known poet at this time, though he's two years younger. Wordsworth has published a couple of poems back in '93. What has been happening, though, is that Wordsworth has just come up to writing his very, very best just at this minute. It's an extraordinary moment. Wordsworth has just written his first very great poem, The Ruined Cottage, and then out of this moment when they meet, come an extraordinary succession of masterpieces from them both. In 1797, the end of 1797, Coleridge writes Kubla Khan, he writes the first version of The Ancient Mariner, which he then completes the following March. Wordsworth writes most of the great poems that come through in lyrical ballads and at the end of the year he writes Tintern Abbey, a marvelous poem which is perhaps too long for us to play now, but it would be great to

Studs Terkel But could we play, I have the, this would be, it sounds like butchery. Could we play part of Tintern Abbey?

Jonathan Wordsworth Well let -- I'd love to read part of it.

Studs Terkel Do you want to read part of it?

Jonathan Wordsworth Well I, I'd rather read myself. Am I not allowed to read myself?

Studs Terkel Of course. Well, forget about Hardwicke. You do very well, by the way.

Jonathan Wordsworth I'm a more melancholy reader than him, but perhaps I can read more quickly than the usual.

Studs Terkel No, don't read quickly. Just read it. Tintern Ab--now, perhaps a preface to it. This is written when, now, and--

Jonathan Wordsworth This is written in July 1798. Wordsworth and Coleridge have been together for a year. And the third person of that group who should never be forgotten is Dorothy Wordsworth, Wordsworth's sister, who has written the, one of the, the first of her great journals, the Alfoxden Journal during this period, who is together with them all the time, and is a wonderfully alive person, the person whose journals record their daily lives but also the life around them in a way that is beautiful, passionate. If you want to know about Wordsworth and Coleridge, read Dorothy. Their poetry is great, but she will give you the idea of what their life was like. So at the end of this year together Wordsworth and Dorothy were walking towards Bristol, which is where the collection of poems of this period, lyrical ballads, was just going to be printed, and they were just in time to put this new poem in that Wordsworth wrote on the way. And he wrote it apparently while they were walking just a few miles above Tintern Abbey. Let me just read you the opening. I'm afraid it would be 48 lines and you will interrupt me.

Jonathan Wordsworth "Five years have past; five summers, with the length of five long winters! And again I hear these waters, rolling from their mountain-springs with a sweet inland murmur.--Once again do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs, which on a wild secluded scene impress thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect the landscape with the quiet of the sky. The day is come when I again repose here, under this dark sycamore, and view these plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts, which at this season, with their unripe fruits, among the woods and copses, lose themselves. Nor with their green and simple hue disturb the wild green landscape. Once again I see these hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms, Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke sent up, in silence, from among the trees! With some uncertain notice, as might seem of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods, or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire the hermit sits alone. These beauteous forms, through a long absence, have not been to me as is a landscape to a blind man's eye: But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din of towns and cities, I have owed to them, in hours of weariness, sensations sweet, felt in the blood, and felt along the heart; and passing even into my purer mind with tranquil restoration:--feelings too of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps, as may have had no trivial influence on that best portion of a good man's life, his little, nameless, unremembered, acts of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust, to them I may have owed another gift, of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood, in which the burden of the mystery, in which the heavy and the weary weight of all this unintelligible world, is lightened:--that serene and blessed mood, in which the affections gently lead us on,--until, the breath of this corporeal frame and even the motion of our human blood almost suspended, we are laid asleep in body, and become a living soul: while with an eye made quiet by the power of harmony, and the deep power of joy, we see into the life of things."

Studs Terkel That's beautiful. So re-reflections on Tintern Abbey and all that comes to mind, far more than a description.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, it's really a reflection on the passage of time. We return again to the period of the French Revolution, because the first time he'd visited Tintern Abbey, the time before the passing of these five years, had been 1793, when he was passionately involved in the Revolution, and he'd actually visited the Abbey in a very strange mi -- state of mind, because he'd just crossed Salisbury Plain, coming away from the Isle of Wight, where he'd seen the English fleet arming for war with France, which was war with everything that he believed in. And of course, it was the country of Annette and his daughter Caroline. And he crossed Salisbury Plain on foot with very little food and very little money, and seemed to have been in a sort of feverish, almost hallucinated state when he came to Tintern Abbey and it made a profound impression on him in its beauty. And he carried this away, and he, what he is recording here is not his impression, not what the, the natural scene does to him immediately, but how it stays with him, how his imagination is charged and fueled by this experience and stays with him and in the, the din of towns and cities he can still feel this amazing sense of seeing into the life of things as a result of this memory.

Studs Terkel So a combination of both there, the, the memory, the, the beauty of the moment, at the same time an undercurrent of despair because of the circumstances.

Jonathan Wordsworth There's always in Wordsworth a sense of elegy, the sense of the sadness of change, of passing time.

Studs Terkel You, you spoke of also of The Ruined Cottage, a long narrative for being one of his major works, too.

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes. I think this is the first of the great Wordsworth poems, it's not very well-known even now, because it became Book One of The Excursion, which is a, a very long narrative poem which was published in

Studs Terkel But listening to this, from The Ruined Cottage, again Wordsworth's--not attraction, but his, his celebration of the ordinary. "You may remember, now some ten years gone, two blighting seasons when the fields were left with half a harvest. It pleased heaven to add a worse affliction in the plague of war: a happy land was stricken to the heart; 'Twas a sad time of sorrow and distress: A wanderer among the cottages, I with my pack of winter raiment saw the hardships of that season: many rich sunk down as in a dream among the poor, and of the poor did many cease to be, and their place knew them not. Meanwhile, abridged of daily comforts, gladly reconciled to numerous self-denials, Margaret"--this is the ordinary farm woman, I suppose, Margaret--"Abridged of daily comforts, gladly reconciled to numerous self-denials, Margaret went struggling on through those calamitous years with cheerful hope: but ere the second autumn a fever seized her husband. In disease he lingered long, and when a strength returned he found the little he had stored to meet the hour of accident or crippling age was all consumed. As I have said, 'twas now a time of trouble; shoals of artisans were from their daily labour turned away to hang for bread on parish charity", here came the bread lines now, "they and their wives and children--happier far could they have lived to do the little birds that peck along the hedges or the kite that makes her dwelling in the mountain rocks." And then it goes on. And now he's describing, is he not, the rough times of the poor?

Jonathan Wordsworth Wordsworth and Dorothy lived very close to these people. They, they had very little money, and they were living at this time in Dorset in the West of England. And although they'd been lent a house which was much more lavish than their neighbors were living in, they were themselves very poor, and in their walks they met these people and they saw the appalling hardships which the Napoleonic War, it wasn't yet Napoleonic, the French War, was causing to the poor, and which Wordsworth had predicted in the early period we talked about before. Wordsworth and others were crying out against the war precisely because it would be paid for by the poor. The rich would, would escape and the taxes would fall as they always do, on the poor. And in this poetry he is recording the suffering that came about. Margaret's in extreme poverty trying to bring up these two children and of course not knowing where her husband is. He has been forced by poverty to enlist and is somewhere dead on a battlefield. Well, more, more likely in fact in the West Indies dead of, of fever.

Studs Terkel So there it is. The poor going to war. Somewhere she makes that reference to a bounty, he's getting a bounty.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well there, he had to, he had to accept this, the bounty for enlistment, and then off he went and she had no

Studs Terkel It's funny how, how--

Jonathan Wordsworth This happened all the time, it was not, it was not--

Studs Terkel No, it's funny, I thought you were talking about 1982. Here it is again. You know? The Vietnam War, of course, here or the young British soldiers in all wars. In all wars, they're the ones, aren't they?

Studs Terkel And, but Wordsworth always--so Shelley was dead wrong, then, when he spoke of Wordsworth as, as changing.

Jonathan Wordsworth No, I wouldn't say he was dead wrong, because Wordsworth in ordinary political terms did become more conservative. I only say that Wordsworth, the man and the poet, retained his ideals. But he saw the political situation as changing. He saw a loss of, of possibility, of achieving ideals through a political solution, and Shelley was still fiercely idealist. But he was that much younger.

Studs Terkel So Wordsworth was looking for another way to achieve that better society, that better world

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes. As did Shelley, really, and Shelley's, has some major political statements. But he, too is, is really a romantic in the sense that he's talking about the achievement of the individual.

Studs Terkel So is this what Coleridge and Wordsworth were talking about, too, when they met? I mean, not disillusionment so much as there has to be another way.

Jonathan Wordsworth There has to be another way. The big difference between the two is that Coleridge was a Unitarian. That's to say he was a member of the foremost radical group in England at the time. They were dissenters, they were unable to be politicians, they were unable to go to the universities, they were kept out, but they were nevertheless the great scientists, the great thinkers, the great radicals of their day, and Coleridge came from this group, and he as it were took on where this earlier influence I spoke of, of the Frenchman Beaupuy left off, and inspired Wordsworth very much with the faith that we see coming through in Tintern Abbey. It is really a Unitarian faith, the ability to see, to make a direct response to the presence of God in the landscape, to see into the life of things, which is God. But Wordsworth, though I think he was a profoundly religious man in a wide sense of the term, was less, less clearly a Christian. Coleridge is offering us, is offering us a belief that has, has a doctrinal basis that Wordsworth doesn't. And I think that it may well be that Wordsworth therefore gets further for us because he inquires into the sources of power always within himself, whereas the ultimate source of power for Coleridge is going to be a God who is at least in some sense external to the self.

Studs Terkel Oh, so that's what Wordsworth was still looking toward, he saw the God in man, and in every man.

Jonathan Wordsworth Yes, as did Blake.

Studs Terkel That sort of transcends

Jonathan Wordsworth -- And really Shelley, and Shelley called himself an atheist, but that, that really meant unbeliever, it didn't mean, it didn't mean somebody who ruled out the spiritual in life at all.

Studs Terkel So Wordsworth is pretty contemporary guy today.

Jonathan Wordsworth Well very -- I think Wordsworth has a great deal to say to everybody. That's why we're bringing this exhibition that we

Studs Terkel What exhibition is that?

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, we're bringing an exhibition over to the States which will start in the New York Public Library and come to the Newberry here, and probably go on to L.A. on Wordsworth and the age of Romanticism, and it will be featuring exactly what we've been talking about, an age starting in the great American and French Revolutions, becoming, becoming dominated by poetry, painting, moving on from Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge into the later Romantics: Shelley, Byron, Keats, and, and coming out, I think, at the end of the exhibition what we shall try to do is to leave the thing completely open-ended. There's Romanticism of many different kinds. We shall end by featuring American Romanticism: obviously, you know, the Hudson River painters; Thoreau, Emerson, among the writers, a number of whom in fact visited Wordsworth, but we expect romanticism to be defined much more widely than that. We hope that the exhibition will be paralleled by other exhibits that people will wish to make. When we take it West we hope people will see the opening up of the West as a Romantic theme, as I'm sure Wordsworth would have done.

Studs Terkel Of course you -- it's extending the whole idea of Romanticism far beyond a literal

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, it's got to be! It's meaningless if you keep it within a, a merely parochial context.

Studs Terkel When is the exhibition take place in Chicago?

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, it's not going to be 'til '86 where

Jonathan Wordsworth We're, we're planning way, way ahead. But you've got to plan way ahead if you're going to make something that's big and good.

Studs Terkel Yeah, yeah, and I trust you'll be here for that.

Jonathan Wordsworth Oh, I shall be here for that.

Studs Terkel You know, I was thinking before you--I'd love to have you end with your reading of another, at least a long passage, if not a, a full poem of Wordsworth, it occurs to me as you're seated here now in front of a microphone, this is high technology, Wordsworth's ode, Intimations of Immortality, and I'm thinking, isn't that funny, as Wordsworth died in 1850. And you, great-great-great something, I must, one too many greats, grandson, so there's immortality is so, is it not? I mean, there is a continuity.

Jonathan Wordsworth You mean, one's immortal in one's descendants. Or, or in my case, in the descendants of a brother.

Studs Terkel So you're a great-great-grand nephew.

Jonathan Wordsworth That's right, yes.

Studs Terkel Well, what would you choose, say, to end our hour of conversation? This is Jonathan Wordsworth is my guest, who teaches at Oxford, and who is here now visiting, talking about poetry, particularly about William Wordsworth at various places in Chicago, University of Illinois Circle Campus. What's one you choose?

Jonathan Wordsworth Well, I'd like to read just the ninth stanza of Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood. It's a bit of a mouthful, that, Wordsworth originally just called it The Ode. The great last--the great ninth stanza in which he looks back and talks about what childhood has meant, can mean, in which he makes the very important point that we tend to romanticize childhood, tend to think of it as just an ideal. That's not really what matters; what matters is the real experiences of childhood, which are not at all comprehended at the time and which feed through. This is Wordsworth looking back. "O joy! That in our embers is something that doth live, that nature yet remembers what was so fugitive. The thought of our past years in me doth breed perpetual benediction: not indeed for that which is most worthy to be blest; delight and liberty, the simple creed of childhood, whether busy or at rest, with new-fledged hope still fluttering in his breast:--Not for these I raise the song of thanks and praise but for those obstinate questionings of sense and outward things, fallings from us, vanishings; blank misgivings of a creature moving about in worlds not realized, high instincts before which our mortal Nature did tremble like a guilty thing surprised: but for those first affections, those shadowy recollections, which, be they what they may are yet the fountain-light of all our day, are yet a master-light of all our seeing; uphold us, cherish us, and have power to make our noisy years seem moments in the being of the eternal silence: truths that wake, to perish never; which neither listlessness, nor mad endeavour, Nor Man nor Boy, Nor all that is at enmity with joy, can utterly abolish or destroy! Hence in a season of calm weather though inland far we be, our Souls have sight of that immortal sea which brought us hither, can in a moment travel thither, and see the children sport upon the shore, and hear the mighty waters rolling evermore."