Wilfred Burchett discusses about his career on journalism

BROADCAST: Oct. 24, 1977 | DURATION: 00:49:30

Synopsis

Wilfred Burchett (an Australian journalist) discusses his journalism career. He was reporting conflicts in Asia (North Korea, Vietnam, China and Japan) and their Communist supporters. He speaks briefly about his experiences in Nazi Germany and concentration camps. Towards the end of the interview he talks about his interest in learning and reporting more about the new euro-communism (prominent in Italy, Spain and France).

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

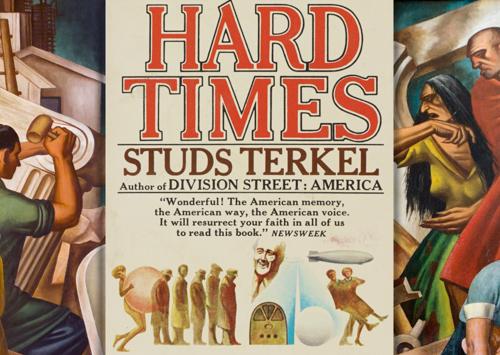

Studs Terkel To me there are two journalists living today I think who are absolutely, they have--maybe there are some more, but there are two I know and I respect and admire very much who are rocklike in their integrity and in their courage. One is my old colleague James Cameron, my old friend in England, and the other is my guest this morning Wilfred Burchett. Will Burchett, the Australian journalist you might say is a universal journalist. He's been everywhere. And very unfashionably, too, at times when it was very unsafe to be there and there he's been, whether it be behind the lines in Korea, whether he's at Hiroshima, whether he--way back it begins with discovering the Sino-Japanese War that you might say was, had the seeds of World War Two in it, and often every side calls upon him because he is right there with his information that others lack, because the information is from his own experience and being there, so Wilfred Burchett my guest this morning after this message. So where do we begin, Mr. Burchett? Your beginnings. We have to come to that.

Wilfred Burchett Well, it's, it's rather strange that you mentioned Jimmy Cameron, because Jimmy Cameron and I were the closest friends in journalism, and when he quit the Daily Express, which was my paper, on a matter of principle, I quit within about 48 hours also.

Studs Terkel Perhaps you should--a little background. This is a paper owned by Lord Beaverbrook, and why don't you set the pattern for that and we're on our way?

Wilfred Burchett Well, it was a very what they call a popular paper, a mass circulation paper with the largest circulation in England in those days, owned as you said by Lord Beaverbrook, and when Beaverbrook lost two of his star correspondents within about 48 hours, he thought there was some plot, some conspiracy between us. But in fact, Jimmy Cameron was away in the Far East at that moment when he resigned, and I was in Berlin for the Daily Express. However, Jimmy Cameron is a very, very great journalist, and you said of tremendous integrity. And it's interesting that he's just written a foreword for, for a new book of mine.

Studs Terkel What is your book called?

Wilfred Burchett It's called How the Vietnamese Survived.

Studs Terkel So shall we begin--perhaps in before--well, how--the --Vietnam. Where were you in Vietnam? And, and we'll, we'll sort of go back, you know, in time.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. Well, I went to Vietnam for the first time after the 1954 Geneva conference had been set up to discuss Korea and, and Indochina. I knew a lot about Korea, I knew nothing about Indochina, so I went down before the Geneva conference started. I went down to Ho Chi Minh's headquarters at the moment, at the beginning of the battle of Dien Bien Phu to find out what that war was all about and to have some background.

Studs Terkel This was the beginning of, and this was obviously a turning point in military history too, as well as in popular war, guerrilla history, that the military of a, an advanced Western government, militarily and industrially, France was knocked off by farmers and peasants.

Wilfred Burchett By

Studs Terkel Now, how did you get there?

Wilfred Burchett I, I came back from the Korean War to Peking and went to see the Vietnamese explain they had an embassy, [if I remember?] two places I think they had an embassy, let's say Ho Chi Minh's Vietnamese in Peking.

Studs Terkel Now, you knew Ho--you knew

Wilfred Burchett But I, but I knew, I met Ho Chi Minh afterwards, you see, so I, I explained I'm going off to that Geneva conference. I know nothing about the Indochina War and it's going to be discussed, I'm to cover the conference. I would like to go down and have a look on the spot. And to my great astonishment they agreed and within a few days I was on my way down from Peking down to the frontier and from there a truck, and after a truck a horse, and finally ended up at Ho Chi Minh's headquarters.

Studs Terkel You were--were you the first of Western journ--one of the very first of Western journalists?

Wilfred Burchett Yes, one of the very first. Perhaps, I suppose, perhaps the first.

Studs Terkel Yeah. Before Lacouture.

Wilfred Burchett Oh, long before, yes, yes.

Studs Terkel So, well, what, what --you knew--you met Ho Chi Minh.

Wilfred Burchett So I met Ho Chi Minh. And the first thing, we got on the way down, the radio was talking about a place called Dien Bien Phu, the radio from Hanoi, French radio from Hanoi, presenting this as some very great victory that they'd parachuted their troops in behind Ho Chi Minh's lines, and they were going to fan out and they were going to wipe out the whole headquarters of the Viet Minh, Ho Chi Minh and all the rest. So I asked Ho Chi Minh, what's all this about, the French are talking every day, every day about a great battle going on, he said, "There's not, no great battle, but there will be. Dien Bien Phu is a valley, the French are at the bottom of it, surrounded by mountains, we're around the top of the mountains and they'll never get out." And he turned his, his sun helmet up on the table in order to illustrate. "The French are way down there at the bottom of my sun helmet. We are all around the rim of my sun--they'll never get out."

Studs Terkel But you did--why don't you go ahead, I'll, I'll just ask you a leading question, so you're on your way. 'Cause I just want to hear you talk Mr. Burchett.

Wilfred Burchett Well, that was, for me that was an int -- my first introduction first of all to Ho Chi Minh. I was, I was terribly impressed by his simplicity, his modesty, by his way of explaining things, he had a vivid image for everything you asked him. He had a, a, a very economic way of

Studs Terkel So here was the helmet turned over, and he shows you that there, these guys are trapped. The, this vaunted Western army.

Studs Terkel Now, when this news finally came that the French were demolished, it still was no lesson taught to the rest of the world, was it?

Wilfred Burchett No, it really wasn't. You see, the United States thought that was, the French lost because they are inefficient and they didn't know how to do it, and they hadn't, they hadn't granted independence and so forth, but if you gave, set up some regime which supported you and used modern weapons, modern technologies, then it would be a, a pushover, The, the United States military people at that time were extremely scornful of French methods of fighting, and they thought if they moved in, you know, it could be done much better.

Studs Terkel So going back before, but, though you in a sense gave warnings to the world, to the Western world certainly, that there's new kind of army here. That maybe it's old as far as history is concerned, an army of farmers and peasants, guerrilla people defending this and they know it as he --who can turn back technologically far advanced force.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. They were fighting. The thing that impressed me immediately, I spent a couple of weeks there traveling around and near the fronts and so forth, the thing that impressed me was that at nighttime the Viet Minh could go absolutely wherever they wanted. And of course in the daytime there were some areas where the French could go. Another thing that impressed me tremendously was that they had built a road to Dien Bien Phu which the French never found out about. I went over that road, and there was all the supplies at night pouring along that road and then just before dawn they'd plant bamboos and trees and all along the road, the French reconnaissance planes never found out

Studs Terkel Now, here's something I'd like to know: How? These are a peasant people, so called. Peasant pe -- they built this road. They didn't have any great machinery. How, how was this road built?

Wilfred Burchett It was built by, by hoes and spades and bare hands. They had no machinery, no road-building machinery whatsoever. They just hacked down the jungle and smoothed it over and carried rocks, covered the rocks with dirt and so forth. And it was a very long road, up and down over terrible mountains, and the French never found out. But there was another thing at Dien Bien Phu which shows the ingenuity of these people who have always been--had to solve problems with a small people fighting against a much bigger power. One say the French never dreamed they could possibly have artillery at, at Dien Bien Phu, the Viet Ming. And all of a sudden the artillery opened up. Point blank. And the Viet Minh had done a, a terribly unorthodox thing. Normally you put the artillery on the other side of the mountain and fire over it, trajectory fire. They put their artillery on the downslope, firing direct, but every time they fired, they let off puffs of smoke in the places where the artillery should have been. And the French never found out about that. They bombed those puffs of smoke throughout the whole battle of Dien Bien Phu.

Studs Terkel So they absolutely deceived. Completely.

Wilfred Burchett They're masters of that, of deception, of ruse, of camouflage, of appearing you know, where they're not supposed to--least expected to appear, and never repeating the same trick twice.

Studs Terkel But all this time you were sending out dispatches, not on these big-time papers but rather these small-time left radical papers, but hardly any attention was being paid to your reports. But finally, they, finally I think that even, even, I think Kissinger called upon you, didn't he?

Wilfred Burchett That's right, [laughing] yes. Yes. That was a very peculi-- a very odd story, really, because I was covering the United Nations, the China debate, China admission debate at the Chi -- at the United Nations, restricted to 25 miles around Manhattan. And then I got a call from Kissinger's secretary, would I come and have breakfast with Dr. Kissinger, I think that was a Friday, the next Tuesday. And I said, "Well, I, yes in principle I quite agree I'll come, but I have a problem." "Oh," said the secretary, "What problem?" "I'm restricted to 25 miles of Manhattan." "Oh," he said, well, in that ca-- --I know nothing about that.

Studs Terkel You were restricted by the State

Wilfred Burchett By the State Department. I said, "But under the circumstances I propose to ignore that restriction." And he said,

Studs Terkel Well I'm thinking, here's a guy, one of the guys responsible for some of that horrors of it, yet even he, I suppose, even he recognized the fact that you knew something that other correspondents didn't know.

Wilfred Burchett Yes, he knew that I knew pretty well, you know, where the Vietnamese stood and what they were after. And he had, I, what I didn't know at that time was that he had broken off his, had unilaterally broken off of secret talks with the Vietnamese, with Le Duc Tho, and, a few weeks earlier, and he was trying to sound out through me how the Vietnamese felt about that. What was their mood? Were they confident? Were they in despair because he'd broken off the talk? That I didn't know that that was his aim at the, until later on. We had a very interesting and very quickly, quick, back and forth discussion.

Studs Terkel What, what's amazing about, most of the public doesn't know Wilfred Burchett. Many of the corres--a number of the correspondents who were a, a lit -- a little more depth than their fellows always read your dispatches. They may do it sec--they read your dis--I notice that The National Review, William Buckley's magazine, which interestingly enough pays you tribute because they recognize the fact that somehow you, though wholly antithetical to what they represent, come out with these facts and perhaps we have to go back to Wilfred Burchett. How did it begin? Why didn't you become a high-paid journalist? You could have made it easily because you and Cameron have a marvelous style in writing and as well as your, your, your gallantry. How come? Start in the beginning. Who is Wilfred Burchett? Where'd you come from?

Wilfred Burchett Well, I'm an Australian, born in Australia 66 years ago. But I had a, a, a peculiar experience when I was still fairly young and was not a journalist by a set of circumstances too long to go into. I was in Nazi Germany between November 1938, March 1939 trying to do something about some Jewish friends of mine and a Jewish brother-in-law, get them out of a concentration camp. So I saw through that, I saw a side of Germany which actually no correspondents, if they saw it they never reported at that time. I went back to Australia on the eve of World War II, and the, the Premier of my state of Victoria had als -- had also just come back from Germany, full of praise for Hitler, full of praise for Nazi Germany. Everything runs on time, it's clean, it's the only stable center in Europe as compared to the decadent French, stories about concentration camps are a lot of nonsense, there's no persecution of the Jews and so forth. And this really, this enraged me, so I started writing letters to the, to the press. "Well, I've also been in Germany, that's what I've seen," without any idea of becoming a journalist at that time. Well, the papers didn't publish those letters because they didn't feel like going against the holy word of the Premier of Victoria who later became Prime Minister Menzies, Robert Menzies.

Studs Terkel Oh, that was Menzies!

Wilfred Burchett That was Menzies, yes. But then, then the war broke out and they remembered this odd Australian that had been bombarding with letters and asked me to describe, to write some articles about what I'd seen. So I started like that, but that taught me a number of things. First of all, that you have to be on the spot yourself. If you're a journalist and you're going to write anything on a, on an issue of world importance, and there's no issue of more, greater importance than war and peace, you have to be there, you have to see it, and you have the--you know, you have to have the guts to write it as you saw it.

Studs Terkel So you were on the spot and you were independent. That's why I must ask this question. During much of the Vietnam War we had American correspondents offering dispatches and they didn't sound like Pentagon or State Department handouts that -- now where were they? They were at a certain hotel, weren't they, in Saigon I suppose, at the Caravelle or

Wilfred Burchett Yes, yes. Mostly at the Caravelle, some of them at the Continental.

Studs Terkel So they write from the hotel!

Wilfred Burchett They wrote from the--oh, not all of them. There were a few very good

Wilfred Burchett Very good frontline

Studs Terkel Homer Bigart [unintelligible].

Wilfred Burchett Homer Bigart and also mentioned in that book of, of [Mackley's?] was Peter Arnett, who was a good AP, a first-class frontline correspondent.

Studs Terkel And Halberstam, too.

Wilfred Burchett Yes, Halberstam, yes. But some of those because they wrote honestly, they, they were pulled back. The Diem regime would demand their recall. And their basic source of news was what was known as the five o'clock follies, the five o'clock briefing given by either the, by the United States--Saigon command, later by the Saigon command.

Studs Terkel You, Wilfred Burchett, then you worked pretty much as this independent solo guy, you know, and on the spot. So there, so you began then. So you began now as a correspondent because of the letters.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. Yes. Then I, I quickly became fairly well known, but then I was convinced also that Japan was going to--first of all, I was convinced, obviously, that Hitler [laughing] was going to go to war and wasn't a man of peace--

Wilfred Burchett Afterwards--yes.

Studs Terkel In the late '30s.

Wilfred Burchett Late '30s. Late 39, yes. And then the, you know, then I got a start in journalism and I told some of those editors, look, Japan is going to come into the war despite everything that the prime minister, Menzies, is now saying. And I would like to go up, you know, I'd like to go up that Burma Road into China and have a look at that Chinese-Japanese War and be on the spot when Japan, as I absolutely, am absolutely certain is going to come into the war. And that's what happened. I went up and I was in Chongqing in, by September of 1941 a couple of months before Pearl Harbor was attacked. Then I became a war correspondent for the London Daily Express covering the China-Burma-India theater at first, and then moved out to the Pacific war, credited to the U.S. fleet as a war correspondent during the island-hopping

Studs Terkel If we go back, Mr. Burchett, always you were there on that spot, and invariably what you--what you wrote about came to pass. And so in Chongqing when you were there, this is the Sino-Japanese War preceding one of the, as the Spanish Civil War was in We -- in the West, this in the East were, were the seeds of World War

Wilfred Burchett Yes. Certainly. Certainly.

Studs Terkel But you always were offering, you saw something there at that time because you were there.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. That's right. I started--some of my dispatches to Australia came to the, the notice of the Daily Express and they were correct, they were--and I was predicting the Japanese were coming in [laughing] coming into the war. Everything pointed that way, and nothing pointed the other way. And so when it actually happened I was immediately engaged by the London Daily Express and was a correspondent for them for the next eight years, but throughout the whole of, of the Asian Pacific part of World War Two

Studs Terkel Now, you worked as a correspondent to--as part of the U.S. fleet? How'd that work?

Wilfred Burchett Yes. Right. Right.

Studs Terkel This is World War II now we're talking about.

Wilfred Burchett World War II, yes. I was accredited to the fleet, and I was with the Marines in all the--not all the island-hopera --hopping operations, but many of the island-hopera --hopping operations [laughing] which eventually brought me with the first sort of wave of, of Marines with the landing on Japan at Yokosuka Bay, at Yokosuka in Tokyo Bay. From there I went down to Hiroshima.

Studs Terkel Hiroshima. So here again you were, perhaps the very first, or one of the very first of journalists who were there after the, after the bomb fell.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. I, in fact I was the, the first, but only by several hours because I--all the correspondents, 600 correspondents who were around there, they were all interested in seeing the signing of the surrender on the, on the Missouri. And I thought the best thing, you know, one must find out what's going on in Hiroshima. So I went down on a somewhat hazardous train journey alone into Hiroshima and later on, some hours later, half a day later--

Studs Terkel Could you do this, sort of can you do this step by step, because here now the bomb had fallen and we know about the nature of radiation. You were taking a train from where to where, say from?

Wilfred Burchett I was taking a train, first of all, as soon as, as soon as we landed at Yokosuka I took a train from Yokosuka to Tokyo. Surprised to find the trains were still running. We believed that they'd all been knocked out with the bombing. And in Tokyo I contacted what was in the Domei news agency. This was several days before they surrendered and signed, and I asked them how could I get to Horoshima and they said straightaway, "Nobody goes to Hiroshima." "Well, I want to go. How can I go?" Said, "Can I hire someone?" I had no idea. I didn't have a map or anything. How far, far it was. And they said, "Well, there is a train which goes every day and which goes through Hiroshima. Hiroshima doesn't exist anymore, it's completely wiped out." So I arranged through Domei they needed some--

Studs Terkel Domei is Japanese press.

Wilfred Burchett That's the Japanese news agency.

Wilfred Burchett It's Kyodo today, in, in those days it was Domei. Anyway, to cut a long story short, they helped me get a ticket for the train, saying "You're completely mad, because nobody goes to Hiroshima." You mentioned there that with all atomic radiation and so for -- we knew nothing about that. We didn't even know the term in those days. Anyway, I got there. It was a 22-hour journey in those days.

Studs Terkel What is it you--can you recall that, the thoughts of people on the train or that you met or what the scenery as you saw?

Wilfred Burchett You know the, my thoughts on the train was that I was in terrible danger all the time because it was a, it was a train which was evacuating Japanese officers and men, and they were, they, they were going south. They were being sent back to other barracks and so forth, distributing, being distributed away from Tokyo because there were some ideas that the army would revolt against the surrender thing and would carry on, and they regarded me with the utmost suspiciousness.

Studs Terkel I was about to say, this is a remarkable moment, isn't it? This is a moment when everything was in a state of flux. Japan was in turmoil, but the Japanese military guys were still around and they see this, whoever this stranger, this Western journalist--

Wilfred Burchett They couldn't work out who I

Studs Terkel So you were under a double kind of jeopardy. There was the danger you didn't know about, radiation, at the same time you were also in physical peril from whatever might be the case here.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. There was an American missionary on the train who the Japanese had brought up to Tokyo to broadcast to the GIs to tell them how to behave. You see? Don't offend anybody. Don't look at women, don't do this, don't do that. It was a very, very tense situation. And he happened to be returning from this to a place called Kyodo, which was about midway between Tokyo and Hiroshima.

Wilfred Burchett -- He said, "Don't smile." He said, "Don't smile. Don't make any gesture, just sit there where you are because you are in deadly danger." All these officers with their big swords and their samurai daggers, [laughing] it was very, very, very tense situation. And Domei had given me the name of their local correspondent. And they said, "We continue to get Morse dispatches from him, but we know he's not receiving our dispatches because everything had been completely wrecked. If you can contact him, he, he will help you at least to transmit your message, and we -- you can tell him that we're receiving his messages," because nobody wanted to go down to Hiroshima. Anyway, I did, was able to contact this, the local Domei correspondent there, and he, he believed me. I said, "I've come," he said, "This is a terrible thing that's been done here." I said, "Well, I've come to have a look, and what had been done, I will report to my newspaper," and he, he accepted that as one journalist to another. So then we proceeded to walk from the railway station which was on the outskirts into the center of the city. And it was like a city which had really been pulverized. In fact, in my first, first sort of few words in my story was it, was this, a steamroller had gone ov -- gone over a whole city that pulverized, where there had been had been concrete was gray dust, where there had been bricks it was red dust, and trams flung off 10 - 15 meters from the side of the road on their sides, with people still inside them, dead. The trees

Wilfred Burchett Yes. Yes. They hadn't, they hadn't completed the--

Studs Terkel And you saw the people, corpses, too.

Wilfred Burchett Yes, in a, in state of inte -- disintegration. And then the trees, we went along a long avenue toward the, the center of the city, and the big trees had all been blown out by their roots. They were like dead cows, you know, with their sort of legs sticking up in the air, stiff. And the smaller ones had withstood because they were, they bent with the blast, but they had no leaves or anything left. And then walked to the center of the city where there were about, I don't know, eight or nine shells of buildings burned out, big concrete buildings which were under the epicenter of the explosion which apparently protected them, and then contacted the police, who were terribly, terribly suspicious. And I,, I met this man years afterwards, years, and he said the police were threatening to kill him and to kill me as well. And why had they brought this Westerner--

Studs Terkel You were probably the first white Caucasian there.

Wilfred Burchett Oh, yes, certainly. Yes.

Studs Terkel You were the first white non-Japanese person there.

Wilfred Burchett And then we went to see, in the outskirts, an improvised hospital where people were just lyin --the patients were laying around--lying around on the floor. Practically all the nurses had been wiped out and doctors, and the only way you could get attention was for a family to come in and bring their family member, sit around, bandages, wounds, do whatever the doctor said, feed him, bring their food and all the rest, because there were no nurses. And this was there, this is one of the worst things I've ever seen in my life, because these people were in fact in a state of physical disintegration. Women, you know, lying on the pillow and all their black hair around them on the pillow, all fallen out, and bleeding from the mouth, gums, so forth. Eyes. And the doctor, doctor came and said, "You must send," he thought I was American, "You must send some of your scientists, some of your doctors here, because we have no idea what to do. We, we thought this was some sort of symptoms of extreme vitamin deficiency. So we started giving massive vitamin injections, but where do we put the needle in, the flesh rotted around the needle, and you must--you go back and get your doctors to, to come down." By that time, I mean, the surrender was actually signed some --somewhere on the train, somewhere along my train route. Anyway, there was, there was such a feeling obviously of hostility by these family members to me that after I'd seen two or three wards, he said, "Look, you bet--you must go, you must go. I can't be responsible for your safety here."

Studs Terkel They thought you were an American.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. And this doctor said, "You know, I'm a Christian. I was educated in the United States, and I simply can't understand that you would have done such a thing. This is not a military target. Here you, you hit the, the civilians, a purely civilian city." In fact, there were some military installations obviously, but "The people who have suffered are, are all civilians". And one thing which struck me, he said, "Everybody here will die, and we'll probably die too, because there are a lot of people here who were not even here when the bomb was exploded. They came back, they were out in the countryside and they came back and started scratching away with their fingers trying to find missing relatives or bits and pieces. And they also, they get this, this strange sickness." And I sat down in the middle of, in the middle of Hiroshima on a block of concrete and wrote my first dispatch, which this Domei correspondent then went back to his little hut and tapped out in Morse. After that, after that there was a planeload of top-flight correspondents being flown out by the U.S. Air Force direct from Washington on a thing, on a, you know, one of those top-flight guided tours, and the great reward for doing that was to be the first group of correspondents in Hiroshima. And they were horrified, at least the colonels in charge of them were absolutely horrified to find another correspondent wandering around, another journalist. They were, "How the hell, who are you? How did you get here?" And they were very unpleasant to me, except Homer Bigart, who was among the team, Homer Bigart--

Studs Terkel The New York Times

Wilfred Burchett The New York Times, yes, who wanted to take my dispatch back because I didn't know whether my Morse-sent dispatch would ever get there. But the colonels, "Oh, we're not going back to Tokyo and we can't be bothered with that." But they never saw--they saw the physical destruction. They were never taken to see that, the hospital that I'd seen, and by the time any other correspondents got down there that, all those people had been removed. They nev--in that story I used the term "atomic plague" and I didn't know atomic radiation, you see. And it was only--that it was denied. It was denied that there could be any atomic radiation. It was denied until John Hersey went down three months later and made a thorough study and wrote a very classical description of what had happened. That was another lesson to me, that you, you have to be on the spot from, for great important issues like having a look at the first, the results of the, you know, first atom bombing. To write that from the headquarters as we were, they asked us to do it, that this was a, a new big bomb, a bomb of much greater power than any other bomb. But they never--you know, the military never revealed what would be the--for me, of course, that would have made a great impression for me, what had happened in the last minutes, one could say of World War II, would be the fate of hundreds of cities in the first minutes of World War

Studs Terkel As you're talking now, Wilfred Burchett, before we take a slight pause for a moment, as you're talking, this quite remarkable, wholly independent correspondent. It's as though you, when you wrote those dispatches, and they appeared as though you're writing from outer space. He was something, a man from another planet it seems. And so again we come to what journalism really can be and should be, in the person of Mr. Burchett. And we'll return in a moment, and post-Hiroshima thoughts and reflections as well as experience and observations of this quite unique journalist. So resuming the conversation with Wilffred Burchett. So there was Hiroshima. Today of course the bombs, the hydrogen bombs and the nuclear weaponry today is what, a hundred fold?

Wilfred Burchett Yes.

Studs Terkel More, more than that,

Wilfred Burchett isn't Probably.

Studs Terkel That was a toy, wasn't it, compared to now?

Wilfred Burchett Yes. Yes. Correct. Correct. Yes, that was the thought in my mind. I'd been a correspondent, you know for, I, I've've seen enormous amount of destruction, but that did pass anything one could imagine before. And it was clear, and that was my reflection [Lord, there?] in the last minutes. A World War II is what will happen to hundreds of cities all over the world in the first minutes of a third world war, which could only be a nuclear war.

Studs Terkel Then the firebombings, but one question, of course, to ask you. This is in, in -- this is invariably asked, and maybe it's conjecture. The justification of Hiroshima often is put forth that Truman was justified in drop it and that he shortened the war, saved thousands of American lives. Now when you were there, you had--the war was almost ending. You think that bomb was necessary to save, or were there other reasons for the dropping of that bomb?

Wilfred Burchett If I look back to my own thoughts at that time, of course I was pleased that the war had ended, and I accepted it well, but I couldn't--

Studs Terkel So many of us did.

Wilfred Burchett But I couldn't swallow the fact that you wipe out an entirely--a hundred thousand or however many civilians in order to shorten the war. We always--until then we've always conceived of the war between military, between armies, people who were trained to kill and be killed and knew the risks they took when they were in, went into the armed forces. Later on of course I knew that it was not necessary. The dropping of that bomb was not necessary. The Russians had already communicated to the United States that the Japanese were ready for--not to surrender exactly, but they were ready to enter into negotiations to end the war. The Japanese at that time wanted to discuss this with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union refused any discussions, but transmitted that to, to Truman. And I think that the, the dropping of those bombs was a, was part of a great power play for after the war and to impress the Soviet Union, you know.

Studs Terkel So it was a political rather than perhaps a military--

Wilfred Burchett I think so, yes.

Studs Terkel So this is one of the questions that invariably arises. You were there and you were also were witnessing the power battles going on. So here you are today, it's 1977. After Hiroshima of course, there was Korea.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. For me there was a brief period in Europe I covered what were, could be roughly called the Cold War in, in Germany. Then, then in 1949 there was, you know the, the victory of the Chinese Communists and setting up of the People's Republic and shortly after that there was Korea. I was still in Europe.

Studs Terkel By the way, did you ever--did you meet Mao and Zhou

Wilfred Burchett I didn't meet Mao, I met Zhou Enlai many times. Many times, from 1941 when I went the first time he was in Chongqing and I had a tremendous impression also. Zhou Enlai and Ho Chi Minh are my two favorite people.

Studs Terkel They are your two favorites. What is it about them? I'm curious, see. What is it about Ho Chi Minh and Zhou Enlai that to you, since you knew them, met them, distinguishes them from other political figures, say?

Wilfred Burchett First of all, both of them were very straightforward. They would listen very carefully to what you asked, and they would give a very carefully thought-out and frank and honest reply. They might sound, "Well, that's not a question we can discuss at this moment," but a simple straightforward frank and--one thing which I'm greatly impressed with Ho Chi Minh was his capacity to reduce very complicated questions to simple images. I mean, there was no, absolutely no pomposity of any sort, it was cut down to the lean.

Studs Terkel Well that's, I can't get over that, that metaphor, that, that thing he did with a turned-over helmet and at the bottom are the French, and he described how a, an army can be trapped.

Wilfred Burchett Right.

Studs Terkel Using some--so throughout those visual simple imagery.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. There was another occasion with, with Ho Chi Minh. That was just after the Marines had landed in South Vietnam at Da Nang in March of 19--when, 1964 or 65? And I saw Ho Chi Minh just after that and at that time because they, the Marines had landed at Da Nang, there was quite a bit of speculation in the Western press that this was the beginning of an invasion of North Vietnam. That they'd push up into North Vietnam, and I saw Ho Chi Minh and asked him what he thought about that. "Well," he said, "You can be sure that Giap, Vo Nguyen Giap, is paying great attention

Wilfred Burchett General Giap, yes.

Studs Terkel The, the man who conceived of the Dien Bien Phu victory.

Wilfred Burchett Dien Bien Phu, yes. You can be sure he's paying attention to that, but personally I don't see it, because it reminded me of a situation where a, a fox gets one foot caught in a trap. And then he starts leaping around to get out [unintelligible], poof! He gets another foot in a trap. And it would be like that if they moved from the south up to North Vietnam. That was his capacity, always when you put some--other people, you know, might take an hour to explain why. [laughing]

Studs Terkel But here, here is Wilfred Burchett, for all the, all the, these incredible events of our day, history-making events, and you, we come back to that theme, you are there. Now we, it used to be, there used to be a, a Columbia broadcast this program, "You Were There", you are well, that's -- you really were! And so that's the only way to write journalism: it has to be first-hand.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. I mean, there have to be also the people who are further back who can analyze, but somebody has to be there and dig out the basic fundamental facts on which analysis and projections and so forth, intelligent projections can be made, it can't be done any other way.

Studs Terkel So you've been China, North Vietnam, Korea, starting from Australia, the U.S. fleet, Hiroshima, Western Europe, behind the line either way, and--

Wilfred Burchett Then Korea came after that, really, I went down for the negotiations on the--for the Korean armistice. And I was there for over two and a half years, and it was after that that I started in Vietnam, then to the Geneva conference on, on Vietnam which lasted for three months, and then back into Vietnam itself. I made my base in Hanoi for two and a half years and visiting Cambodia, Laos, a couple of times Saigon. And then I went to Moscow because we'd, by that time we'd expected, according to the Geneva agreement, there would be elections in Vietnam to reunify the country in July 1956, well, July, July 1956 had come and gone and there was no prospect whatsoever of--

Studs Terkel Ho would have won overwhelmingly, would he not? Ho would have won overwhelmingly.

Wilfred Burchett Oh, yes, there's no, absolutely no question. No question. And I thought well, it's, I've been dealing with all perimeter problems 'til now, Germany, Korea, Vietnam, and it's better to be in one of the two power centers really. So I went to, I went to Moscow for a few years. But then, then Vietnam again started impinging itself on my journalistic consciousness, if that's the way to express it. There were, kept getting reports there was fighting going on in the south. And so I started going back from 1962 I went all around the frontiers, trying to find out what was going on. And then in 1963 I went in with the Maquis, with the guerrillas in South Vietnam for about five months.

Studs Terkel You called them "Maquis," that's interesting. That's, this is, this -- we think of the French underground. There's a great irony here.

Wilfred Burchett Right. I live in France now, so I've picked up some of those terms. Anyway, I went in to find out for myself what had happened, where it had started, why the fighting started, what it was all about. And I went, I went altogether four times with the guerrilla fighters, with the NFL in South Vietnam.

Studs Terkel So you, you lived with the guerrillas, too.

Wilfred Burchett Well, I tru--yes, I wa--yes, yes. I was based with them, we were, we were on the--living is, that's not the right word because we were on the move all

Studs Terkel Were they--as you lived with--were they pretty certain, were they certain they were going to win, did they--what was the feeling? Were there self-doubt?

Wilfred Burchett No, they were quite certain. They were quite certain. There's something--that unless one has, you know, studied a little bit of Vietnamese history, there's something -- there is this factor, that for 2000 years they've always been fighting you know, against, always against forces--

Studs Terkel Invading.

Wilfred Burchett Invading, and enormously

Studs Terkel Including China, by the way,

Wilfred Burchett China was there for 1000 years in one stretch, and invaded 50 times again after that period. Then were the Mongols, you know, the world-conquering Mongols, and they took them on three times--

Studs Terkel And the Japanese.

Wilfred Burchett Then the Japanese. French, Japanese, French again, then the United

Studs Terkel And finally we. But we learned, it seems to -- here's this history, and yet we didn't know, we didn't learn.

Wilfred Burchett No. That's true. I think, there's a--I really think there's a blockage in the, you know, in the military mind on some of these things.

Studs Terkel I'm -- you are in the midst of this cauldron, this maelstrom. And at, at a, at a turning, always turning points in world history. I've got to ask you the question that I find so incredible. How can you explain, you were in Moscow? You were in Peking? You're respected on all sides. How can you explain the Sino-Soviet conflict or is it explainable?

Wilfred Burchett Ahh. It's very difficult to explain. It's very difficult to explain. It started with ideological dissensions, matters of how do you build communism or how do you build socialism? It started that way and then it developed into political things. China was very annoyed when, when Khrushchev went to Camp David and came away to try and persuade China about the Camp David spirit and so forth. But China already, there was the Korean War, it was--just been finished and, and United States troops were occupying Taiwan. And then there was the economic thing. The Soviet Union pulled out its experts and stopped building factory. It started as an ideological thing and ended up as it is today, a state-to-state thing where you've got the whole works, including frontier disputes, disputed frontiers, and the whole

Studs Terkel It's almost beyond ideology, it had so much as though there were two powers, one, two of the two superpowers and the other growing. It seems like some national has nothing to do with ideology or does it? Is this

Wilfred Burchett No, it, it started with

Studs Terkel Strange phenomenon,

Wilfred Burchett It started with ideological dispute and gradually worked its way up the spiral until it included everything.

Studs Terkel Now the question to ask you, 'cause if anyone can answer it, if it's answerable, you, you would be the one. Is it irreparable?

Wilfred Burchett I think that it's irreparable for a very, very long time. I think the, the maximum that one can expect is that they do arrange a status quo on state-to-state relations, including the question of the frontiers. But for the rest I think it's a--Mao at one time said "Well, it'll take 10,000 years." Then later on he said, "Well, we might knock a couple of thousand years off."

Studs Terkel Yeah. And maybe a couple of hundred years after that, yeah. But

Wilfred Burchett Very deep, it runs very deep on both sides.

Studs Terkel Well how, how dangerous is it? That's an academic question.

Wilfred Burchett No, I think it is dangerous. I noticed, I noticed the other day in The New York Times Harrison Salisbury's description of the enormous deep tunnel of anti-nuclear tunnels and an enormous amount of energy and technology are badly, are very scarce and badly needed technology going into that. That depressed me very much because it meant that the Chinese really believe that they are in danger of, of being attacked, and that they, well, they really believe that there's a possibility of a, a war between the two major socialists powers.

Studs Terkel A number of years ago, Salisbury was pointing out, he said--he--I think he was the first one to alert the rest of the world to the fact that along the frontiers were these enormous amount of troops, both sides.

Wilfred Burchett Yes, he has taken the view that it's inevitable. I, I don't like to think

Studs Terkel No, but it's, it's incredible. And of course both are playing up to the United--his --I suppose, I suppose, I suppose if some would call irony exquisite. There is an exquisite kind of irony here and both of these countries

Wilfred Burchett True.

Studs Terkel Are playing up to the United States.

Wilfred Burchett Right. Right. It's, yes it's the, the triangle.

Studs Terkel What are you--well, here we come now to, to you, to Wilfred Burchett, who's been everywhere. You've been third world country aside from Asia?

Wilfred Burchett I've been, last year I spent a good deal of time in, in Angola and Mozambique, three times Angola, twice in, in Mozambique.

Studs Terkel I can't, I can't get over the fact, you and Jimmy Cameron, I, I must tell you, this is a story that's a Wilfred Burchett story. When I heard about Bangladesh at the time, I said to my wife, I says, "Cameron's there." And sure enough, next day dispatch, Cameron apparently dead in a ditch. He was in a jeep that collided -- and of course he's, he's invulner -- [laughing] he's immortal, as he says. But there is--that's you. So wherever something is happening, there's Burchett and there's Cameron.

Wilfred Burchett It was even worse with Cameron there that, you know he had just got married to a lovely, a beautiful Indian--

Studs Terkel Yes, Moni Cameron.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. And he was on his honeymoon in India and this war broke out. "You know I, you now I have to go."

Wilfred Burchett And did. And the be -- and the jeep was bombed.

Studs Terkel Yeah, that was it.

Wilfred Burchett The other two people, there were three people, a driver and two other. They were all killed. And he was the only one, with both, I don't know, legs broken,

Studs Terkel That's right. And they flew back to England and he's full of plastic as he says and everything. Various

Wilfred Burchett -- He says he has to be wound up every morning.

Studs Terkel He is, he's wound up and has nice some Bell's scotch.

Wilfred Burchett Right,

Studs Terkel But I'm coming back to something he described, now I'll ask you. He says as he lay in that ditch practically dead, he saw walking along the road thousands, and the word came to his mind, the key word of our time, "refugee." Refugee. And they, of course they paid no attention to him. Because they would look straight ahead, I suppose if there is the word, that is the word of our day, isn't it?

Wilfred Burchett It is, and I mean it's typical of Jimmy Cameron in this terrible plight in which he is himself [laughing] that he's thinking of some greater tragedy than his own.

Studs Terkel But I'm, I'm thinking about you and he.

Wilfred Burchett Yes.

Studs Terkel And your sense of history, why you two are remarkable journalists, aside from the immediacy of what they're doing, you sense the historic connotation to it.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. I don't know why we were built that way, but I think that

Studs Terkel I know you have a number of engagements, and I'm holding you way over, but I've got to ask for some kind of prognosis. You know I'm one of these yo-yo's, I wake up sometimes pessimistic, sometimes optimistic. If something good happens, I feel good, next day feel awful. What do you see? What, what is the one phenomenon of our day that impresses you at this moment and considering all your travels and experiences and observations?

Wilfred Burchett Well, as I have been closely, and, and this doesn't really answer your question, but as I've been very closely connected with observing and I must, can say supporting, national liberation movements, for me the great storm center, you see, has shifted from Asia and Southeast Asia to, to southern Africa. And I think this is a great new drama, everything which is going on there, and which will involve mighty forces. I think, I think that there will be armed struggle, and armed struggle will continue in Rhodesia, Zimbabwe, and Namibia. I don't believe that, I don't believe that either Smith in Rhodesia or Vorster in South Africa are going to give up by some reasonable negotiations and plans and so on and so forth. And I think we're heading up to a very big, a very big confrontation in that area, but I, I don't see this developing into some new, new [third?] war. I, I don't, I don't see any sort of physical sort of expeditionary corps ex --intervention by, by, well by the United States or by anybody else there in that area, but I think that's the, that's the new big thing that is shaping up. The other thing is of course the development of, of nuclear weapons, and now the neutron bomb which is the most horrib -- [laughing] horrifying thing I've ever heard

Studs Terkel Well, property, property comes out okay.

Wilfred Burchett Right, that's

Studs Terkel I mean, this table won't be here. You and I might not be here, dear sir, but this table will be.

Wilfred Burchett This is absolutely fantastic consequently, the fact that, you know, it could be more or less officially called the "clean bomb" that only kills humans.

Studs Terkel You know, it'd be a great bomb if you're, especially if you're a chair. [laughing]

Wilfred Burchett Yes.

Studs Terkel Now, coming back to one other thing: you speak of the liberation movements, and so the colonial powers are kicked out, and here, this is Cameron again talking if I quote him again, he says, "You know, and we're told when a tyrant comes along, a Black tyrant or a tyrant who is Asiatic, after the white colonial powers have gone, and the Colonel Blimps always 'See, we told you so. They can't govern themselves,'" and Cameron says, "What examples have they been given?" And then the key question is, you must let the people overthrow their own tyrants.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. I quite agree. I quite agree and I think that the only, the liberation movements and the independence movements that have been successful have been those where the leaders of those movements have taken the people into their confidence, have tried to study the aspirations of those people, and have had the full support of the people. Of course, they'd have to have strong, they'd have to have strong, disciplined, centralized organizations, either movements or parties to direct those movements, but always in participation with the people. That's the thing which struck me in, in, you know, from Vietnam and Mozambique, for example. Wherever you went, the people were wholeheartedly and consciously on the side of their leadership, which were guiding the, guiding the struggle. And people have to overthrow their own tyrants. I absolutely agree in that.

Studs Terkel Where next for Wilfred

Wilfred Burchett Well, I'm starting to look into something else, which all rather fascinates me, as everything new does. I'm starting to look into what is behind the, this Eur --what is known as Euro-Communism. What are the roots

Wilfred Burchett What's behind--where is it leading to? Well, what are its perspectives and so forth. And I intend more or less after I finish this present tour to start having a, a look into the roots--

Studs Terkel You're thinking about, about Berlinguer of Italy--

Wilfred Burchett Berlinguer

Wilfred Burchett Carillo of Spain. And of course Marchais.

Studs Terkel Marchais of France. And here is a new, what appears to be a new development.

Wilfred Burchett Yes. It is, it's new, whether you like it or not, or, it exists, and it's, it's going to exist. And so I want to have a good long look at that and then try and come to some conclusions in some way. Anyway, to find out what it's about and publish

Studs Terkel You know, I think as you're talking, I'm delighted of course to have met you. Through the years of, whenever a chance I've read your dispatches, and by the way, you've been praised by The New York Review of Books, New York Times Magazine, Bertrand Russell of course. And Phillip Knightley, who wrote The First Casualty, in which he, he lambasted many war correspondents, but two who came off unscathed were Wilfred Burchett and, and James Cameron. But one thing seems to me to be quite obvious in your case: wherever something is happening that might alter, one way or another, the human condition of the world, there's Wilfred Burchett. Thank you very much.

Wilfred Burchett Well, thank you for having had me along and given me the chance to express my opinions on all sorts of questions.