Interview with Norman Thomas - part 1

BROADCAST: Dec. 30, 1964 | DURATION: 00:33:04

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

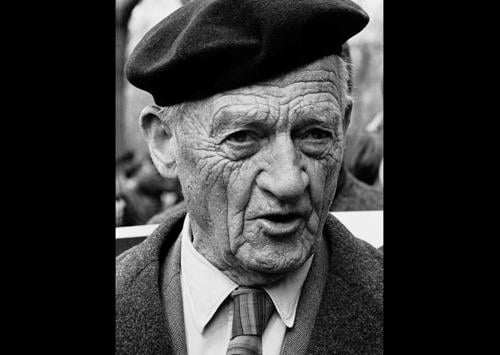

Studs Terkel It's the 80th birthday of Norman Thomas. Now, you know it's eighty years. [mic check] Now. Now it's moving. Norman Thomas, 1884-1964. Norman Thomas perhaps the last, I hope that isn't the right phrase, but the last of our colorful dissenters, six times candidate of the American Socialist Party for President of the United States, his 80th birthday being celebrated by fellow enthusiasts in human rights and peace movements throughout the world, really. Mr. Thomas, the first question is a whopper, a leading question. 1864, 1884, 1964. Is this world, one we live in now, a better one than the one you entered in 1884?

Norman Thomas I don't know. If we're having a high school debate, I could debate either side. In some ways, better. We have made social progress. We had to! The question is, does our social progress keep up with the demands of our technical and scientific progress, and I don't think it has. Where we have lost is in having to have two World Wars and the consequent immersion in violence that followed. This is, I think, the great tragedy. The better side certainly won in both wars, but the ends of the war, the ideal ends for most, emphatically, lost. The first war allegedly was fought by us, at least, to make the world safe for democracy. It wasn't fought by our allies for any such purpose. The Second World War-- I heard a most eloquent speech about how not only was it going to get rid of Hitler, but that it was going to get rid of militarism. We have had such a militarism as the world never dreamed of. The last time I looked it up, we spend a world in which two thirds of the people live on a borderline between hunger and starvation. Spent 120 billion dollars, and I think it's more now, on getting ready for another war which could end the world, as far as human beings are concerned. Now, in that situation, it's very hard to debate. I look back at the turn of the 18th century into the 19th century. There were over a hundred causes for capital punishment in Britain. Prisons were terrible. They aren't too good now, but they were terrible. Our treatment of the insane was tragically awful. In things like that, we made very considerable progress. We do have a sense of social responsibility for poverty, which is much greater than it was. And we have, on the whole, in my lifetime, at least since the First World War, made progress in the judicial protection of free speech and free press and so forth. You'll notice I emphasize judicial because our great trouble in America now, strangely enough, isn't the courts, although they sometimes go wrong, I think. Our great trouble is the people to whom we used to appeal. It's the people who really don't believe, or a great many of them, don't believe in free speech and who go to considerable lengths to prove they don't.

Studs Terkel Well, isn't this incredible? The courts this time are the pillars of free speech for the people, and isn't this sort of a chicken coming home to roost? The very mass media that became frightened in the last election were the ones conditioned, perhaps, to [unintelligible] --

Norman Thomas Well, but-- chickens coming home to roost, but one of the great disappointments of my life is that I have less instinctive confidence in the people than I had earlier or in the labor movement. I believe in both. You have to, you live here and you work. I belong to a union. I think unions are indispensable. But I can no longer feel as strongly as I once hoped that if we could get stronger labor, civil liberties should be protected, civil rights should be protected. On the contrary, in civil rights it's taken quite a while to get the unions to take a really decent position and some locals don't get.

Studs Terkel Why, doesn't this lead to a fascinating and disturbing question? For years, you and those who are called "utopians", quote unquote, yet very practical, dreamed of the century of the common man of the people. And yet what is it? Where then, is the hope? The individual?

Norman Thomas Hope's got to be in a lot of individuals. Everything good begins with minorities. Now, I'm a great believer that you have to have democratic government by majority, but it begins with the minorities. And I think there has been, excuse me, a failure of us, however you classify us, to do the work that we ought among our fellow citizens. It has been a failure of education. When you get a situation where your intellectuals, generally, or at least a large number of them are advanced civil libertarians and civil rights people, but they haven't well communicated it. Teachers haven't succeeded in teaching it. I remember a college boy who said to me, "I think all of my college professors are liberal," but he said that doesn't really make any difference. They don't have much effect.

Studs Terkel They don't have much effect. And yet, these minorities, down through the years whom you have represented, are one of the most eloquent spokesmen for, it is they, then who must continuously--

Norman Thomas They have to keep up [work?]. I used to shrug my shoulders, and I still think it more a legend than fact, about how [Ken Goodman?] might have saved Sodom and Gomorrah. But he couldn't even [find? buy? unintelligible]. But it is the minorities, especially the minorities that begin and that puts a great responsibility on those of us who have a pretty clear view of what we want. You called me a dissenter a while ago, and I'm quite proud to be a dissenter when one ought to dissent. And I have insisted all my life that the right to dissent is precious and absolutely essential to true democracy. Nevertheless, I'm not primarily anxious to be remembered as a dissenter. It's positive things. The right to dissent is a positive right. The right to equality between races is a positive right. The right to abolish poverty, the possibility of abolishing poverty, these are things that concern me more. A lot of dissenters are damn fools, too.

Studs Terkel Then the question dissenting is for something affirmative, for something positive.

Studs Terkel So it's a question of disturbing the waters, but the waters of complacency.

Norman Thomas That's right. It's the question of that, and it depends on, well, let's get to that. I don't know how to follow through that simile of yours.

Studs Terkel I was thinking that sometimes we tend to be self righteous and satisfied. We-- I suppose I speak of the great middle class. That's a question! I want to ask about your own beginnings and childhood, and your own secrets of vitality. The values we have that you spoke of the people awhile ago, the working man. Aren't his values then pretty much middle class values?

Norman Thomas Oh yes, sure. We're so prosperous, and I'm not going to break down and cry about it. We are so prosperous, and the middle class values have some significance. And the the employed worker in a strongly organized union, sure, he's got middle class values. He's a little better on the whole. The unions, as a rule, are better resolutions and a lot of other middle class people don't realize that unions give fairly generously to other things outside themselves out of their funds.

Norman Thomas Nothing wrong with it. It's a little like a church, you know. They adopt very good resolutions. And the churches I was talking a while ago, I ought to have said the churches have improved since I got out of them, so to speak. They are taking a much better stand, at least on top on civil rights, than they ever used to. The Protestant churches, and to some extent the Catholic, used to be the most Jim Crow institutions in the United States. They are trying not to be, at least the better of them are.

Studs Terkel Mr. Thomas, you were once a Presbyterian minister. Why did you leave the ministry?

Norman Thomas Well, I didn't exactly leave the ministry. It wasn't a simple process. The minister left me. That is, the church left me. The-- if I had stayed in the parish in the very poor district Upper East Side of New York in which I worked holding the views I did at the time of the First World War, they would have--they would have been paralyzed because people would have withheld gifts. So I resigned, thinking then that I'd probably go back to being a clergyman. And I had liked to be a clergyman, in those days, very well. But one thing led to another. If I had wanted to go back to the First World War, I couldn't have. Not for a good while. And when perhaps I wanted, my thinking had undergone such a change that it didn't seem to me quite the honest and honorable thing to do. I by no means had become an atheist, but I by no means held the-- even the liberal orthodoxy of my church. And I doubt how--I'm not for great creedal conformity, but I think there are some honest limits. For instance, I'm not a great admirer of people saying the Apostles Creed when they don't believe it, or don't believe large parts of it.

Studs Terkel What's an old phrase is--there's an old phrase by Tom Paine: an infidelity consists of not not believing, but professing believe what you don't believe. Something like that.

Norman Thomas I think that a great deal of thought that ought to be given to it. Of course, now I want, in all fairness, to say that in the Christian church including the Catholic Church now, the advance liberals would say they believe it, but they believe it in a symbolic sense, or something like that. This I am too much of a square always to follow.

Studs Terkel Thinking of Norman Thomas now. People will ask the secret, the secret of his ebullience, vitality and at the same time, not unadulterated optimism, because a while ago you said something-- you have doubts, questions about the common man-- beginnings, Mr. Thomas. Marion, Ohio, and of course the crazy thought occurred to me. You were born in Marion, Ohio, the home of another American and political life of our second century, Warren Gamaliel Harding. Isn't there a parable here somewhere, the two streams in America?

Norman Thomas I'm not the man to make a parable. Somebody else can make a parable. But my life was curious in its coincidences. I was born in Marion, Ohio, and I knew the Hardings. Mrs. Harding really ran the paper on the business side, and for a time I carried papers. I knew them. They were much that, on the surface, at least which was likeable. He was not qualified for the tremendous post he got, but he-- I always remember that he pardoned Debs, at least. And Wilson didn't. Well, what I was going to say was, here I was, I came from Marion and I carried papers for Warren Gamaliel Harding, I went to Princeton and sat at the feet of Wilson, and look how I turned out. It's kind of tough on educators isn't it?

Studs Terkel Think of Marion Ohio itself, 1884, early part of the century. Norman Thomas, how you came to be what you are. Early influences. Were your parents a factor?

Norman Thomas Oh, great factor. I was most fortunate in my home. My father and my mother held far more orthodox views, far more, shall we say, puritanic Victorian views than I hold today. But they didn't make it, make life a veil of tears for their children. They were awfully good parents, and they held the view that it was natural to be decent, and they rather taught and inspired that kind of view. So I have--I'm not one of those who's made what I am by a revolt against my parents. I don't hold all their convictions, but I am profoundly thankful to have had people who so honorably tried to live up to what they themselves believed. They were good neighbors, good friends, and all that. I believe some things they didn't, but I have my home to be thankful for.

Studs Terkel The beginnings of last time that I remember talking, it was a time Lillian Smith was your colleague at the microphone, and spoke of beginnings, and she said her parents also are very decent, but they accepted the ritual of segregation as part of life and spoke of your parents accepting the ritual of war as being-- they were good decent people--

Norman Thomas Well-- my father he died before we got into the World War. He was beginning to question it. He was a clergyman. He was-- he thought he was more orthodox I think than he was, because of the years after his death, one of his congregation told my sister an interesting story. She had been worried about the doctrine of predestination. She had asked my father what it meant, and he said, "Well, I think my dear, it merely means that our God is not surprised." Now, I don't think that's so such sound Calvinism as maybe my father did, but it shows the tendency. I have sometimes said it rather jocosely that my father believed in Hell. Not a literal place of burning you know, but something equivalent to it. But I never could get him to say anybody was going there. "Neath the saddle on the ground, mercy saw [sown?] is mercy found," which is what one of the Wellesleys said when the village drunk fell off his horse. Now, I don't believe in it, but I could-- I would--I could, with difficulty, be restrained from malinating candidates. I don't.

Studs Terkel I think you duly speak of your father doubting the predestination the theme you yourself, a while ago was speaking of doubts you have. Progress. Progress is not something automatic, is it?

Norman Thomas Oh, I want to say that! It's been hard to learn because there is a popular author-- what's his name? I know him well. Walter, Walter-- Lord. He wrote a book, he wrote a lot of books, but one of them called "The Good Years". Walter Lord. And the good years were the years between 1900 and 1914, before the war. looking back on life, I think that it was extraordinarily well named. Good years for Americans like myself. We knew there were a lot of things wrong, but we thought they were quite easily-- or not quite easily, but but changeable. We didn't believe there could be any very great wars anymore. We believed in progress with a capital P and it was an awful shock when the things happened that did happen to us, a shock from which I think mankind hasn't recovered. Our present malaise is, I think, partly attributable to it. I no longer live and believe in that kind of progress. I wrestled with myself, and the best I've come up with is this. I certainly don't believe there's a sure divine event to which this world moves. On the other hand, I do not believe that we're damned, either by our genes, which is one possible way, or by our gods--whatever they are. And since we aren't damned, you can get more joy out of life if you'll bet that this mankind, which is after all, done extraordinary things both in virtue and vice, is capable of going farther.

Studs Terkel So even though the gamble is bigger, yet the element of chance here-- not chance so much as opportunities for people who call themselves minorities to work seems so much greater.

Norman Thomas Yes they are! And of course we now have tools. It is once our glory and our shame that man has been able to invent such extraordinary tools and to get such extraordinary control over energy, the powers of nature. The shame is that we used the chiefly for war, some of our greatest power, and that we've not lived up to ourselves. That is to say that we can't control ourselves and we can't manage our social institutions, anything like as well as science and technology enable us to send our voice around the world, for instance, enable us to record this talk and able man to orbit the earth. Things that nobody dreamed of!

Studs Terkel At the same time, as we have these-- these technological advances that put us on the threshold of something unprecedented, we still don't seem to have the wit to match it as far as a social--

Norman Thomas I'm not sure. As I see our present time, not only don't we have the wit, but we sort of don't have the courage. A great deal of our literature is a literature of acceptance. Well, after all, we don't amount to too much.

Norman Thomas Yes, and we-- the best we can do is to be kind of forgiving of ourselves and others. There are those who boast that evil is good. I don't go along with Sartre in finding this-- what's his name? This [Parisi--?]

Studs Terkel Genet.

Norman Thomas Genet. I don't go along with that kind of business. I don't go along with life. You know, there was a popular novel. "A Ship of Fools".

Studs Terkel Katherine Anne Porter.

Norman Thomas Katherine Anne Porter. Who said she was one of them in her preface, if I remember.

Studs Terkel You or something else you feel. We're ripe for something else aren't we. This alienated man we've been singing about so long becomes a little old hat now. And you feel somehow that we're ripe for something else?

Norman Thomas And we are ripe for-- well, we've got to be ripe for something else. Two things have happened, well more than two, but two things particularly have happened that make it necessary for us to be--to do something else. One is the first, and most obvious, is that war, which was the supreme arbiter of our disputes, and which has been intimately bound up with man's evolutionary progress. Some relatively good things have come by at some very bad things, but war is-- we say we hate it, but we've also cherished it from the very beginning of any human society. Now you can't do it if you want to live. Not if the war becomes extensive, because we have weapons of obliteration and it's going to be hard to adapt ourselves to that, especially since we live, still, under the religion of competitive military nationalism, which is a very bad religion. Patriotism, really loving your country, and loving as your love your family is one thing, but there's the religion of nationalism-- excuse me-- which sanctifies everything to itself which advances its ends is a very bad thing. Any religion that does that is bad. The religion of white supremacy is bad. The Christian religion when it tells that you had--the only hope of heaven along one particular road. Therefore, anybody that didn't go on that road could be persecuted. Tortured. That's a bad religion. We got rid of some of that, now we got to get rid of the kind of religion of nationalism which sanctifies murders long as its in the name of your side.

Studs Terkel Same time, just as man can destroy himself whole, he would also, on the threshold of abundance, for our--

Norman Thomas And that raised its own problems. And for an old socialist like me, it's quite quite difficult. Now here it is: we socialists used to assume that if you've got proper management and got prosperity, it would be because everybody was working not so hard, the machinery would help. But now, we know we can get an enormous degree of prosperity in a country like the United States with lots of people not working. And with the further growth of cybernetics that will be more true. And that's the second thing that changes the whole picture. We've got to get used to an economy of abundance instead of an economy of scarcity, and that that involves different values, somewhat different standards, different methods. I assume that we will come to a time when out of a general income, which would be very large, we'll make grants to people simply being born into the American family the way you would if you were born the Rockefeller family. But that raises problems. There was some value in the job income nexus. We've got to teach people to work creatively, to seek for service callings, like teaching and nursing and so on. And we've got quite a problem ahead that a young fellow like you may have to reckon with that problem. I'm probably going to pass on. But you know, if history goes as history has gone, the people who invent, own, and program the machine so bosses-- machines can't strike, and it'll take some education and some planning to get them, to get this straightened out. And yet we have, for the first time in human history, a chance to conquer poverty, conquer bitter poverty, which the Bible says "the poor ye have always with you," and so we did. Now, if we can extend cybernetics, and if we can control birth, you can breed ourselves out and if we can avoid ore, and if we can conserve natural resources halfway reasonably, you've got a chance of abundance for all. You've got a chance of a world with a great deal of conquest of disease and all the rest of it. It was Hobbes, I think, that said that for the great majority of men, life had been poor, brutish, and nasty. I think that was the order he had put them. And I think that's pretty true. But it needn't be true as regards our control over natural forces is concerned.

Studs Terkel Mr. Thomas, since you've cited scriptures, wouldn't this also call for a re-evaluation of our Puritan ethic that as man shall earn his bread by the sweat of his brow--

Studs Terkel It'll

Norman Thomas call for a reevaluation of that too, wouldn't it? For a redefinition of work! Of course, you'll have to have a redefinition of work. And that isn't so easy. But there is-- the kind of work that a great, great many people had to do was--can't because [they had?] to be a blessing. But the notion that you are contributing to the sum total of what is necessary by which you and your family and the world live was very valuable. It was a good discipline for us. It is, you know, I guess as Paul says "he that will not work, neither shall he eat," which is a pretty severe judgment. But nevertheless, there you are.

Studs Terkel All this redefinition of work that you implied earlier, that is, instead of working for things, you spoke of service work.

Norman Thomas You have to do lots-- you'll have to develop the idea of service and you'll have to develop the creative instinct that you're working when you're making something, which may not be of great material value. We have got to find some way in which man will work under compulsion other than the necessity to eat. A good many people who chose the right father or grandfather, man has to work for that.

Studs Terkel Why is it that we always worry about initiative being destroyed if people receive an income when not working, but if someone clips coupons, his initiative has never [been tried]?

Norman Thomas I know. We lived in a society when you ought to work so that you could make so much money so your descendants didn't have to work. It's a very peculiar ethic.

Studs Terkel Someone spoke of the possibility of there being an Athens again. Then there were human slaves. There need not be human slaves, but mechanical slaves. That work can be redefined as creativity of all sorts.

Norman Thomas Yeah, I know. I even said that myself in speeches, but I'm not so sure. In the first place, I have to remember various facts about Athens. Its glory was very short. Athens destroyed itself a good deal by militaristic and imperialistic ideas, and it was, after all, the free citizens of Athens who condemn Socrates. And I don't think it is possible to do what they ought to have done as long as they rested on slavery, even though their slavery seems to be much less cruel than it was in Mississippi, more than life is now in Mississippi. That's something to think about.

Studs Terkel Thinking of the mechanical slavers, this word again cyber-nation, automation. So then, you are thinking of socialism with a past dependent upon the idea of full employment. Yet, some economists say that never again will be full employment.

Norman Thomas That's right. And full employment and jobs when you did have the nexus between the job and your income.

Studs Terkel So this raises an-- So things cannot really be the same, can they. looking back now eighty years.

Norman Thomas You can take-- I'm a socialist and you can take some of the socialist ideals as very basic, you know. What I, frankly, thought for years was an impossible goal, beautiful as it was: "from every man according to his ability to every man according to his need" becomes a possibility, and possibility of a highly ethical society, and a highly successful society, only it requires the developing of sides of man that haven't been to much developed.

Studs Terkel Norman Thomas, this leads to matters now perhaps less tangible, less material involved, yet things that are on people's minds a lot. On yours, I know, and others who lived through most of the century. Certain losses of the word color comes to mind. You a very colorful man, yet we know in political life today, and for that matter in life everywhere, seems to be a lack of -- is this imagination on my part? I mean, men of political [effect?] like Gene Debs, Bob LaFollette, George Norris.

Norman Thomas Well, that's certain types were products of this last century in the early part of this. But I would have said that the former President Kennedy was, in his way, a very colorful man. I think we got colorful men that-- the color is rather different now. I think some of our heroes of the racial struggle are decidedly colorful men. I think in his way, Martin Luther King would call that-- depends on how you define it.

Studs Terkel I suppose the word flamboyance maybe something I'm looking for.

Norman Thomas Yes, this is curious. I find it very hard to reconcile my old ideas of a demagogue derived from the 19th and early 20th century with the people whom I would call demagogues or the equivalent now. For instance, I think that Goldwater, in theory, is-- in his proposals was pretty demagogic, but he isn't demagogic in manner in speech.

Studs Terkel Huey Long, say-- As against Huey Long--

Norman Thomas There's a beautiful illustration. Look at the difference--or not like [Violet?] Coglan, whom you remember. Or a lot of others that we remember a while back and it interests me that that Mr. Welch is the president of the Birch Society. He's done a, from his point of view, a terrific job and getting so strong an organization. And yet, to medium, to hear him speak, or especially to hear him debate. He has no particular--

Studs Terkel Personality.

Norman Thomas Personality. No color, no charisma, they say nowadays. And yet, look where he's got!

Studs Terkel Well, I think this is a fascinating point. We have to dwell on it because I know what concerns our world, it concerns this matter. Even the demagogue- let me say this- even the demagogue is a colorless, a automatic sort of man in contrast with--

Norman Thomas Well, if his ideas-- it's singular, it's very singular. There was a man in a very different sphere that-- this'll make some of your hearers annoyed, but there is a man and a difference. Fear. Buchman, who was the Oxford Movement and laid a--

Studs Terkel Moral Re-Armament.

Norman Thomas I knew him when, and I could no more have picked that he become the figure in the world of the religion that he did than anything. It's just amazing, because he also didn't have that outward. His friends will probably write you letters telling us what he had, and probably Mr. Welsh as well. But, if you get some good ones, let me know what they say.

Studs Terkel I certainly shall! I think this question of good ones, even good letters that are entire-- sort of refreshing. It's the ones that are, I suppose, what colorless and [shell?] that that's what a little depressing isn't it? But you don't mind a good antagonist!

Norman Thomas No you don't, but you hate that antagonist who calls you all kinds of names and then doesn't sign his name, for instance. And you hate the fact that so many people-- Antagonism now, to a large extent is expressed so, so cruelly. I know dissenters who were persecuted by continual phone calls at night, by sending [Hearst?] in front of their house, by sending their wives obituaries. That shocks me. Did I already refer to it? Think of the-- bomb threats are now a dime a dozen! People don't carry them out, of course, or rarely, but you can never assume they aren't going to carry them out. I think that I was told that in the Rockefeller campaign for the presidency, and he's no blooming radical, they got more than a hundred bomb threats out there in California.

Studs Terkel Doesn't this lead to something-- you say bomb threats a dime a dozen. Here again, the question people continuously talk about, almost cliche matter now, is the indifference of man toward toward man. And they speak of the girl in the hallway being killed while twenty watch, or the boy on the ledge being urged to jump, and then they forget the phrases Hiroshima and Auschwitz don't they? Because aren't these connected?

Norman Thomas I think that you have--we're people of contradictions. We can love and hate, almost simultaneously, the same person or the same object. We-- traditionally, people have loved and hated or both. And we are capable of being highly shocked by--after the event of Hiroshima and so forth, Nagasaki, and the rest of it. But we're quite capable of doing it again. The great--the great-- there are two things that I have never really recovered from. You may remember that in 1910, you wouldn't know it yourself, but you may have read it-- that was the year that Norman Angell wrote a book that was a best seller all over the world called "The Great Illusion" in which he proved that war didn't really pay anybody. Not big wars. If I remember rightly, and I'm not sure I do, even the Kaiser said it was wonderful. Four years later, they fought and they kept on fighting when everybody was losing. In other words, an irrationality of hate and cruelty that comes in there. And this was an awful shock. And then, that we didn't learn from that but went on and had a second World War in which a man was even more cruel. Hitler, and what he did, and Stalin for that matter. This is a big shock to me. It's also that right now, I can't get any more excitement out of the churches, which are awakening on some questions, to this war in Vietnam. I think we're doing a shocking thing! I think men of good intentions may have started it thinking they were gaining something by it, but what we did was to intervene in a civil war. Intervene a thousand times more than the Chinese and the North Vietnamese have intervened. Our allies haven't got a stable government under them. We've had a revival of-- we've had what didn't happen in Asia. This the first time in history that I know of that Buddhists have engaged in a sort of a religious--.