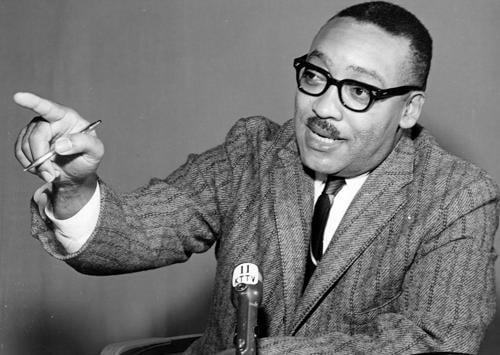

James Cameron discusses his experiences as a Brittish journalist and his book "Point of Departure" ; part 3

BROADCAST: Jun. 4, 1973 | DURATION: 01:01:23

Synopsis

Studs Terkel interviews James Cameron about his experiences as a journalist that includes thoughts about Cameron's book, "Point of Departure." They talk about his relationships with Winston Churchill, Lord Beaverbrook, Charlie Templeton, and Bertrand Russell. Cameron discusses his education, poverty, and the depression during his youth. They talk about Cameron's career with the "News Chronicle" and his home of Dundee, Scotland. This is part 3 of a total of 4 parts. The interview takes place at Lewis and Clark Community College.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel Well, thank you Norm. This morning is part three of a four-part program with the British journalist, one of the most distinguished of our time, James Cameron. His reflections, thoughts of the past 30 years, experiences, and his conclusions, if any, and as though one does have conclusions. In a moment after we hear from Norm Pellegrini a very slight intro and then part three of James Cameron. The world's greatest living journalist. His autobiography, "Point of Departure", is out of print, perhaps could be reissued, is a beautiful book. And during the past--today we have a third day, when I met him again at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, we talked. His experiences in early Scotland as a journalist during the Korean War, the first man to expose Syngman Rhee, his experiences in Africa and the Middle East, in China, the first Western journalist in North Vietnam. Firsts are one of those things that don't matter too much, but there he was in the very early moments when it was unfashionable to re-investigate those matters and he did. And later on turned that he really was--he really had it. So we pick up part 3, his own reflections way back to childhood now, with James Cameron. Continuing the conversation with James Cameron and for the past two hours been talk about his life as a journalist, people he's seen, thoughts he's had, the police, refugees, makers and shakers of one sort or another, and I'm thinking about your life. During the last time you mentioned childhood. I know in your marvelous autobiography, "Point of Departure", that McGraw Hill published a number of years ago, you spoke of Dundee, the industrial area of Scotland where you first became acquainted with journalism and your father, a lawyer who wrote in a certain style. [Resh?] to him. You also mentioned France, I didn't know this, France played a role in your life, in your boyhood?

James Cameron Well, my father, you see, with whom I lived until he died, was a barrister, an advocate, an attorney I suppose you'd call him here, but a very, very unsuccessful one. He discovered a talent for writing novellas, books, not very great ones, but good enough. And in those days, the economic situation in Europe was completely different from what it is now. That is to say, the pound sterling was worth far, far more in Europe than it was at home. Whereas now it's worth about half as much. But, so, my father said, "Let's go over and live in France because if I earn a pound, we'll be able to live on it for probably a whole week," you see. So we went to France and every month my father would discover a new heaven on earth. "This is the great place, this is where we'll stay, what a marvelous little café here, we'll live above it, have great fun." And six weeks later he'd say, "You know, it's not all that good. I've found another better place, it's about 150 miles away, let's go there." Well, the result was that my education, if you can call it an education, was sketchy beyond imagination because I was always being bumped off from one school to another. I went to about 30 different elementary schools, and such is the strange quality of the French educational system in those days that the minister in Paris was supposed to be able to look at his watch anytime and say, "It is two o'clock in the afternoon. I have 2,300,000 children reading Racine at this particular moment," he knew everything that was happening, it was so systematized. So if you were shoved around as I was, you were always going back to square one, you see. So I emerged from this process having learned to multiply the five times table but no more, and having learned to read so, I was very, very undereducated indeed. And, therefore, when it became necessary for me to suddenly earn my living, I obviously sought my living in which other trade would accept somebody who is illiterate in two languages at once and couldn't count beyond five, obviously journalism is the trade who would accept me and that is how the dreadful stories began.

Studs Terkel Roughly, what year is

James Cameron This is in the late 1920s, 1929 or '30s, and then I went to Dundee, which--

Studs Terkel Then you went to Dundee.

James Cameron Well, I went to Dundee straight away because my father had gone to live there after the death of my mother. It was--he had reverted to his ancestral ground when he realized that he was alone and defeated. He retreated back to the womb, which was Scotland and was Dundee. At that time, this was deep in the middle of the Depression, and of all the depressed areas in the United Kingdom at the time, Dundee was quite the worst. There was a period in my life when I first became aware of the world around me when we had 48% unemployment in the town itself.

Studs Terkel Forty-eight percent.

James Cameron Forty-eight percent. Let's say one man in two had a job of a sort. And I didn't know what this was all about, but all I realized was that I was growing up, and I was a child of 18, 19, something like that, in the midst of really unforgivable poverty, because we didn't have the welfare state as well-organized as we now do, and people were living on a "dole," as we call it, what a contemptuous name to give Social Security, dole it was called, 14 shillings a week, you

Studs Terkel I remember a play, "Love on the Dole", Wendy Hiller. "Love on the Dole".

James Cameron Well, anyhow, I didn't know what it was all about. I just knew there was something wrong with the system or society that permitted this to go on when down, down the River Tay, about 10 miles or so, there were jute millionaires living in enormous houses and doing [selling?] considerable state.

Studs Terkel What jute mills the

James Cameron Jute was the only industry in the city except there were three J's, jute, jam, and journalism. They were the only things they

Studs Terkel Jute, jam and journalism.

James Cameron Yes. Keeler's Marmalades. Dundee marmalade, you see, was made there. But none of these were prospering, and I didn't--you see, I had no political education. I didn't really know, I didn't understand how you would go about solving a situation like this, I just knew that it was wrong and something had to be done about it. That then started me reading. My father, who's in my mind's eye then a very old and wise gentleman, although he was five years younger than I am now. He presented certain people for me to read and so on. And I realized that the only answer to this particular sort of anomaly in society as we see it now is socialism in some form or another. And then I learned how to apply it, or I tried to learn. I never really learned much about it because politics as an end in itself never in the least interested me, I was totally uninterested in the ends of politics, but it seemed to me that the new means were important if people were to be given half a chance of living in some conditions of decency. But you can return to the city of Dundee today which is now prosperous, full of IBM machine, manufacturers, typewriters, calculating machines, all light industries now, no longer all this heavy industry stuff, and you still see the old people, 60 and 70, going around with bent legs because of rickets. Curved spines because of malnutrition. They still hoard the social scene. Even now we have a welfare state. The survivors of the great injustices of the '20s and '30s still live to challenge societies today, or so it seems to me.

Studs Terkel That when you returned, and how you became a journalist in the late '20s, early '30s now, the Depression. The American Depression coincided, or, perhaps the British [depression coincided with the?] American Depression, the worldwide depression there, too, then it would happen in Austria, too, and we know also how Hitler came, too, in Germany, but so we come to you and Dundee, now you became a working journalist and you had a style and a point of view.

James Cameron It was very many years before I was allowed to do any writing in journalism. Journalism to me in my early days consisted of filling paste pots for my betters, sharpening the pencils, and putting the old back numbers on the files. I had two or three years of that, and I didn't regret it for a single moment. And then after that I became a [weekholder subeditor new color copy holder?] And I went through all the processes, every single process in the whole business of newspaper production which was possible in this firm because wrong though it is, it was absolutely non-union firm. It forbade the print unions and to this day still does. Well, I deeply deplore that situation, but by hindsight, it was very useful to me because it allowed me to do almost every--

Studs Terkel Variety.

James Cameron Variety--

Studs Terkel Then you went to London--how did--and then you worked--

James Cameron Then I went to London and, then almost simultaneously the war began. I arrived in London and the war arrived in Europe at the same time. People were--

Studs Terkel We're now talking about '39, aren't we?

James Cameron We're talking about '39, '40, I actually arrived in the end of '38, beginning of '39, '40 began and we were ver--the whole newspaper industry was extremely hard up for people because everybody was drafted into the army, you see. I had been drafted in and drafted out again because I'd been invalided out because they reckoned that I hadn't got good enough health for it. As it turned out, they were dead wrong because I lasted out at least five wars, more than most of them did at the time, but therefore--

Studs Terkel Now the byline of Cameron as we know appeared, that's the point, isn't it?

James Cameron Yes, that towards the end the war, really after the invasion of the continent of Europe.

James Cameron Yes, that was the beginning of it, really.

Studs Terkel And was--you were working for now Lord Beaverbrook.

James Cameron I was then working for Lord Beaverbrook's "Daily Express", yes.

Studs Terkel Now, Beaverbrook be would be at that time, perhaps, equivalent to, say, to William Randolph Hearst, one of the--he had two papers at the time, did he not, at the time? Beaverbrook.

Studs Terkel He was the big publisher, wasn't he? He was

James Cameron He was the very big publisher. He was Canadian. He was not only a big publisher, but he was also a very important member of the government, minister of aviation production.

Studs Terkel Under Churchill.

James Cameron And he was a great confidant of Churchill, they were great buddies together. A couple of brigands, if you ask me, but nonetheless--

Studs Terkel A couple of brigands, you say.

James Cameron Yeah, but Beaverbrook had a, there was a kind of majesty about his wickedness in the sense that he wasn't in the business to make money like all the other newspaper writers I've ever encountered who only want to make money. Beaverbrook had made all the money he wanted, he was a triple millionaire by the age of 28, so all he was in was to make propaganda overtly and without any shame at all. He told the Press Commission that we had at the end of the war, "I am in newspaper production in order to propagate and promote my political point of view and for no other reason at all." Well, the political point of view that he was trying to promote was outrageous to me, but I rather more admired that than I would admire the people who are only in the thing to make a swift buck, you see.

Studs Terkel But the fact is, you challenged him. Now, we

James Cameron

Studs Terkel Well, thank you Norm. This morning is part three of a four-part program with the British journalist, one of the most distinguished of our time, James Cameron. His reflections, thoughts of the past 30 years, experiences, and his conclusions, if any, and as though one does have conclusions. In a moment after we hear from Norm Pellegrini a very slight intro and then part three of James Cameron. The world's greatest living journalist. His autobiography, "Point of Departure", is out of print, perhaps could be reissued, is a beautiful book. And during the past--today we have a third day, when I met him again at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, we talked. His experiences in early Scotland as a journalist during the Korean War, the first man to expose Syngman Rhee, his experiences in Africa and the Middle East, in China, the first Western journalist in North Vietnam. Firsts are one of those things that don't matter too much, but there he was in the very early moments when it was unfashionable to re-investigate those matters and he did. And later on turned that he really was--he really had it. So we pick up part 3, his own reflections way back to childhood now, with James Cameron. Continuing the conversation with James Cameron and for the past two hours been talk about his life as a journalist, people he's seen, thoughts he's had, the police, refugees, makers and shakers of one sort or another, and I'm thinking about your life. During the last time you mentioned childhood. I know in your marvelous autobiography, "Point of Departure", that McGraw Hill published a number of years ago, you spoke of Dundee, the industrial area of Scotland where you first became acquainted with journalism and your father, a lawyer who wrote in a certain style. [Resh?] to him. You also mentioned France, I didn't know this, France played a role in your life, in your boyhood? Well, my father, you see, with whom I lived until he died, was a barrister, an advocate, an attorney I suppose you'd call him here, but a very, very unsuccessful one. He discovered a talent for writing novellas, books, not very great ones, but good enough. And in those days, the economic situation in Europe was completely different from what it is now. That is to say, the pound sterling was worth far, far more in Europe than it was at home. Whereas now it's worth about half as much. But, so, my father said, "Let's go over and live in France because if I earn a pound, we'll be able to live on it for probably a whole week," you see. So we went to France and every month my father would discover a new heaven on earth. "This is the great place, this is where we'll stay, what a marvelous little café here, we'll live above it, have great fun." And six weeks later he'd say, "You know, it's not all that good. I've found another better place, it's about 150 miles away, let's go there." Well, the result was that my education, if you can call it an education, was sketchy beyond imagination because I was always being bumped off from one school to another. I went to about 30 different elementary schools, and such is the strange quality of the French educational system in those days that the minister in Paris was supposed to be able to look at his watch anytime and say, "It is two o'clock in the afternoon. I have 2,300,000 children reading Racine at this particular moment," he knew everything that was happening, it was so systematized. So if you were shoved around as I was, you were always going back to square one, you see. So I emerged from this process having learned to multiply the five times table but no more, and having learned to read so, I was very, very undereducated indeed. And, therefore, when it became necessary for me to suddenly earn my living, I obviously sought my living in which other trade would accept somebody who is illiterate in two languages at once and couldn't count beyond five, obviously journalism is the trade who would accept me and that is how the dreadful stories began. Roughly, what year is it This is in the late 1920s, 1929 or '30s, and then I went to Dundee, which-- Then you went to Dundee. Well, I went to Dundee straight away because my father had gone to live there after the death of my mother. It was--he had reverted to his ancestral ground when he realized that he was alone and defeated. He retreated back to the womb, which was Scotland and was Dundee. At that time, this was deep in the middle of the Depression, and of all the depressed areas in the United Kingdom at the time, Dundee was quite the worst. There was a period in my life when I first became aware of the world around me when we had 48% unemployment in the town itself. Forty-eight percent. Forty-eight percent. Let's say one man in two had a job of a sort. And I didn't know what this was all about, but all I realized was that I was growing up, and I was a child of 18, 19, something like that, in the midst of really unforgivable poverty, because we didn't have the welfare state as well-organized as we now do, and people were living on a "dole," as we call it, what a contemptuous name to give Social Security, dole it was called, 14 shillings a week, you know. I remember a play, "Love on the Dole", Wendy Hiller. "Love on the Dole". Well, anyhow, I didn't know what it was all about. I just knew there was something wrong with the system or society that permitted this to go on when down, down the River Tay, about 10 miles or so, there were jute millionaires living in enormous houses and doing [selling?] considerable state. What jute mills the private Jute was the only industry in the city except there were three J's, jute, jam, and journalism. They were the only things they produced. Jute, jam and journalism. Yes. Keeler's Marmalades. Dundee marmalade, you see, was made there. But none of these were prospering, and I didn't--you see, I had no political education. I didn't really know, I didn't understand how you would go about solving a situation like this, I just knew that it was wrong and something had to be done about it. That then started me reading. My father, who's in my mind's eye then a very old and wise gentleman, although he was five years younger than I am now. He presented certain people for me to read and so on. And I realized that the only answer to this particular sort of anomaly in society as we see it now is socialism in some form or another. And then I learned how to apply it, or I tried to learn. I never really learned much about it because politics as an end in itself never in the least interested me, I was totally uninterested in the ends of politics, but it seemed to me that the new means were important if people were to be given half a chance of living in some conditions of decency. But you can return to the city of Dundee today which is now prosperous, full of IBM machine, manufacturers, typewriters, calculating machines, all light industries now, no longer all this heavy industry stuff, and you still see the old people, 60 and 70, going around with bent legs because of rickets. Curved spines because of malnutrition. They still hoard the social scene. Even now we have a welfare state. The survivors of the great injustices of the '20s and '30s still live to challenge societies today, or so it seems to me. That when you returned, and how you became a journalist in the late '20s, early '30s now, the Depression. The American Depression coincided, or, perhaps the British [depression coincided with the?] American Depression, the worldwide depression there, too, then it would happen in Austria, too, and we know also how Hitler came, too, in Germany, but so we come to you and Dundee, now you became a working journalist and you had a style and a point of view. It was very many years before I was allowed to do any writing in journalism. Journalism to me in my early days consisted of filling paste pots for my betters, sharpening the pencils, and putting the old back numbers on the files. I had two or three years of that, and I didn't regret it for a single moment. And then after that I became a [weekholder subeditor new color copy holder?] And I went through all the processes, every single process in the whole business of newspaper production which was possible in this firm because wrong though it is, it was absolutely non-union firm. It forbade the print unions and to this day still does. Well, I deeply deplore that situation, but by hindsight, it was very useful to me because it allowed me to do almost every-- Variety. Variety-- Then you went to London--how did--and then you worked-- Then I went to London and, then almost simultaneously the war began. I arrived in London and the war arrived in Europe at the same time. People were-- We're now talking about '39, aren't we? We're talking about '39, '40, I actually arrived in the end of '38, beginning of '39, '40 began and we were ver--the whole newspaper industry was extremely hard up for people because everybody was drafted into the army, you see. I had been drafted in and drafted out again because I'd been invalided out because they reckoned that I hadn't got good enough health for it. As it turned out, they were dead wrong because I lasted out at least five wars, more than most of them did at the time, but therefore-- Now the byline of Cameron as we know appeared, that's the point, isn't it? Yes, that towards the end the war, really after the invasion of the continent of Europe. You cover that? Yes, that was the beginning of it, really. And was--you were working for now Lord Beaverbrook. I was then working for Lord Beaverbrook's "Daily Express", yes. Now, Beaverbrook be would be at that time, perhaps, equivalent to, say, to William Randolph Hearst, one of the--he had two papers at the time, did he not, at the time? Beaverbrook. Yes, he did. He was the big publisher, wasn't he? He was the very big publisher. He was Canadian. He was not only a big publisher, but he was also a very important member of the government, minister of aviation production. Under Churchill. And he was a great confidant of Churchill, they were great buddies together. A couple of brigands, if you ask me, but nonetheless-- A couple of brigands, you say. Yeah, but Beaverbrook had a, there was a kind of majesty about his wickedness in the sense that he wasn't in the business to make money like all the other newspaper writers I've ever encountered who only want to make money. Beaverbrook had made all the money he wanted, he was a triple millionaire by the age of 28, so all he was in was to make propaganda overtly and without any shame at all. He told the Press Commission that we had at the end of the war, "I am in newspaper production in order to propagate and promote my political point of view and for no other reason at all." Well, the political point of view that he was trying to promote was outrageous to me, but I rather more admired that than I would admire the people who are only in the thing to make a swift buck, you see. But the fact is, you challenged him. Now, we come-- In Perhaps

James Cameron Well, I'll tell you what happened. I had been working, this was in '45 and '46, I had went out with Sir Stafford Cripps to India with the mission that was to try and find some accommodation with the congress government and with Mahatma Gandhi, and well, so that independence could be given to India because by this time we had a Labor government which was committed to the end of the Empire.

Studs Terkel We're talking now about when Churchill was beaten by Attlee.

James Cameron That's right. After '45--

Studs Terkel Inspector Cripps was the minister of--was he--

James Cameron He was brought back from being ambassador to Moscow and he became Chancellor of the Exchequer. And then finally he was given charge of the entire negotiations for the, what was in fact the wind-up of the British Empire.

Studs Terkel So you and Cripps were in India.

James Cameron Yes. And [reverting? referring?] to Beaverbrook, however, you see, I worked there for about a solid year and a half without ever seeing the paper I was working for and I was really quite unaware of what an awful organization it was, because Beaverbrook, being a confidant of Churchill, was vigorously and violently opposed to any suggestions India should receive independence or in fact that any colony should be given any measure of independence at all. As Winston Churchill said, "I have not been made his Majesty's first minister in order to preside over the disintegration of the British Empire." However, that was exactly what Clement Attlee, the then prime minister, reckoned that destiny had called him for, but I didn't realize that I was writing for a paper that was terribly hostile to Indian independence, so I continued to write the sort of stuff that I'd been writing for years and years past, and I never saw the paper at all. And they--we return to the thing we were talking about self-censorship before, they published every line of it, they always published an editorial beside it saying, "This is a lot of nonsense," but still. But when I, after this was over, I was brought back to London for, I suppose, a bit of brainwashing or something, or rest and rehabilitation or whatever it might be called. And then I suddenly became aware of what a very unpleasant outfit it was. And there came an occasion which was politically important to us but of no importance here in which a cabinet minister was violently attacked because he had once been a Communist.

James Cameron John Strachey. And I couldn't swallow

Studs Terkel it. John Strachey was minister of de--

James Cameron Of

Studs Terkel Of war under Attlee, quite a remarkable figure, and Beaverbrook, if I recall your marvelous autobiography, Jim, "Point of Departure", you were in some other country, whether in India or you were in Hong Kong, headline of a paper--there were two papers, the one you were not working for, [Beechly? Beachley?], same employer [of?] Beaverbrook, had a headline: "Strachey wins, so does Klaus Fuchs."

James Cameron That's right. Because Klaus Fuchs was a very celebrated traitor, a German communist who'd been working on the nuclear proposition with us and had possibly quite legally, correctly, been convicted and sent to prison, and he betrayed the country, okay, but completely unjustly, it seemed to me, they identified our minister of defense with this man because he had happened to have an acquaintance with him. And I thought, you know, this is so stinking, because here comes Senator McCarthy galloping over the horizon into our political scene. I didn't want it, and so I left them, but it seemed to me a silly thing to just leave them because of some negative thing. Who the hell cared whether I was working for him or whether I

Studs Terkel The city, you were at the time the highly, perhaps the most highly-paid journalist in British history, you

James Cameron I wasn't so highly paid, but I was--

Studs Terkel Highly respected.

James Cameron Pretty highly regarded.

Studs Terkel Yeah, and you decided to--well, what happened when--you saw that headline--

Studs Terkel Thing with your publisher.

James Cameron Couldn't be done. I--

Studs Terkel With your story at all, you see.

James Cameron No.

Studs Terkel But you did something.

James Cameron Well, I merely said, "I think that if this is the attitude of the administration of the film for which I'm working, it'd be impossible to continue working for it. Is that so, yes or no?" And the editor summoned me forth and said, you know, "How much did the opposition offer you to do this?" And I was so outraged, you know, I said, "Isn't it possible for you to conceive that somebody can hate you for yourself alone?" And so I couldn't, I said I want nothing, I leave as from today. No golden handshakes and no money, no nothing at all. And I went home and my heart in my boots. Yes. And I summoned a meeting in my family, I had three children then, and we had a family conference. My wife and my three children, we, the youngest one was only four. So we allowed him to be present at the meeting, but we didn't allow him voting rights, and the rest we voted should I stay or should I go? And they said, "Well, we didn't know anything about this situation, but if you want to go, you've got to go." So I went. And it was a very, very traumatic thing, made an enormous sensation in Fleet Street because nobody had in fact spat in this old man's eye before, and--

Studs Terkel Beaverbrook.

James Cameron Yes, and he--then you see, I said to myself, "Well, nobody will really care, and I want to get him. I just don't want to leave him on, I want to get him." And so I wrote a long letter to "The Times" knowing that doesn't eat dog and they'd never print it, but it was nice to get it out of my system. "I have left the employment of Lord Beaverbrook because I consider he is a copper-bottomed shit for the following reasons: a, b, c, d, and I posted it and I said, "Well, that's fine, it's out of my system. I'll put my note to Santa Claus up the chimney." And of course, to my horror the next day, they let the letters [with it?], they printed it, okay--

James Cameron Then, of course, all hell broke loose, because Beaverbrook was a very, very important member of the newspaper proprietors association, as it was then called, and he put it around, not unreasonably from his point of view, that either I must be a card-carrying member of the Communist Party in Great Britain or I must be nuts, and possibly both, well, either of those two challenges was quite enough to keep me out of gainful employment for several years to come, and it was a very tough time.

Studs Terkel Were you blacklisted then?

James Cameron Well, there was nothing so formal as a black list, it was just very difficult to get work.

Studs Terkel But then here you were. Everybody knew you in England, you were a celebrated journalist. Then others, you were hired, then others asked for your services.

James Cameron Well, yes, that's quite true. And by dint of working, really, very, fairly hard and also by trying to learn my trade rather carefully. I mean, I do not honestly believe this [dramatic? romantic?] idea of [kitchen?] journalist. Anyway, you've got to know your, listen, you've got to know the business of communications inside out, you've got to know the business of telecommunications, got to know the business of radios, you've got to know everything you were, you simply--my long stint with the Dundee organization where I even learned how to set type and how to carry type around, they couldn't, you know, faze me with science now, I knew it all. And this also was rather useful, but you don't go going around saying, "Look, here am I, a Simon-pure fellow, I'll give you the holy word on something," I've got to know to get my copy in on time, I've got to know how, if they ask for 800 words, I've got to give them 800 words, not 820 words. This is--

Studs Terkel This is the point. Also I notice that when you and your--Cameron, buy the way, has been on BBC a good deal, and here again your ease, with time, you know, but also it's more than just knowing the clock, it's knowing the use of words, doesn't it? The economical use of words as all but your own style that's bare, at the same eloquent comes into play.

James Cameron Well, you're using bricks, you see, if you're building a wall you've got to know where to put the mortar and where not to put, every trade has got its tricks, you see. I consider that I'm a tradesman, Studs, see, I've always bitterly opposed this business of calling journalism a profession. I have--where they talk about the profession of journalism I've always denied it, I've said, "I'm not a professional man. A professional man is one who has passed an examination in order to enter a certain field of activity and that field of activity can apply sanctions to him and expel him if he fails to live up to their levels." Well, journalism has none of these things at all, so I have to tradesman, but I was trained to be a bloody good tradesman.

Studs Terkel Yeah, you call yourself a tradesman, perhaps craftsman might be the word. At the same time, you have certain standards that are so high that U Thant, former head of the UN, has called you the most important journalist of this century, and other journalists in reading your autobiography have spoken of how you have lifted the levels of journalism, not just in England, but in other parts without other journalists being aware of it, you see, so call yourself a tradesman if you will, but I call you an artist or a craftsman, well, go ahead. So by this time, you had challenged Beaverbrook and this was shocking. And now you worked for other papers, "Picture Post", you spoke

James Cameron Well, then we had the similar debacle, the Syngman Rhee thing, so by that time with one thing falling hot on the heels of another thing, I really was considered to be the nutcase of Fleet Street.

Studs Terkel Fleet Street, by the way, for people listening, Fleet Street is a street of the newspapers, right?

James Cameron Yeah. Streets of the Fleet. Anyhow, after a lapse of some years which were not very easy, I finally fell in with the newspaper that I loved best of all, which I'd always in my heart wished to work for, a thing called the "News Chronicle", which was a silly, in a sense bumbling, rather unprofessional newspaper which called itself a liberal paper and it was exactly the sort of paper I wanted because it's--anyhow, its attitude was exactly what, without going into details, it was a very beautiful organization to work for, and for 13 years thereafter I worked for it as its foreign editor and as foreign correspondent and then--

Studs Terkel For the "News Chronicle"?

James Cameron Yes. And then in the fullness of time you see that the proprietors found that it was being uneconomic. They happened to be, make most of this chocolate over the world, and they found chocolate was more profitable than newspapers, and so they killed it.

Studs Terkel You say your publishers made chocolate.

James Cameron Yes. Cadbury's.

Studs Terkel Well, did that chocolate have anything to do with their interests?

James Cameron Well, in the sense that it started to turn them into a lot of soft centers. No, it was just that there was another example of a big business organization treating the production of the newspaper as another extension of a boot-blacking factory or anything else, whereas I've always argued that a newspaper had certain obligations that transcended the necessity simply to make money. Of course, it's got to make money or it won't survive. But this has got to think of something else, too, and the old "News Chronicle" had done that, and that was why I had 13 delightfully happy years with

Studs Terkel Was it during the time that you were at the "News Chronicle" that you had visited Lambaréné? At the time we heard a great deal about the saintly doctor in Lambaréné, Albert Schweitzer, the Bach organist, the doctor, and this is, again, you caused something of a stir. I think something very unfashionable.

James Cameron Yes, but--well, I went to see him to begin with that was unfashionable, because he didn't let people go there and also in those days 20 years ago, it was extremely physically difficult--

Studs Terkel We'll return in a moment to the story of James Cameron's visit to Lambaréné and his revelations concerning Albert Schweitzer. After we hear from--we're talking to Jim Cameron, distinguished British jour-- correspond (sic), who's more or less in these four hours, this being the third, reflecting about his life and his craft. Resuming the conversation with James Cameron. When last we left, as they say in soap operas, he was in Lambaréné, Africa visiting Doctor Schweitzer.

James Cameron Extremely physically difficult to get there. This was long before the days of airlines dropping you all over the place, it was very, very difficult indeed. But I finally got there because I had been like most people, a tremendous admirer of the mystique of Schweitzer who had surrendered all these academic gifts and all, all the things he could have had in order to work with the Blacks in the Gabon. Eisenhower went there, and I stayed there with him for some weeks and I must confess what I saw distressed me very much because he was not what I thought he was. He--the great hospital of Schweitzer at Lambaréné was not created for Africans but it was created for Dr. Schweitzer. He was a immensely self-centered egocentric man who despised Blacks but made use of them, a man who told me the very first day I ever met him that he considered that the greatest potential savior of the whole African continent would be Daniel Malan, who was then the prime minister of South Africa.

Studs Terkel Let's stay with this a minute, Jim, because you've caused quite a few upheavals journalistically in the lives of a number of people and disturbed their psyches. The saintly Albert Schweitzer admired Malan. Malan was the father of apartheid in South Africa.

James Cameron Malan was the father of apartheid, and Dr. Schweitzer practiced apartheid to an even stronger degree than Dr. Malan did. In all my experience, Dr. Schweitzer never would allow a Black to sit down in his presence, for example, simple as that. But there are a multitude of things that I could say against him, but this it must be said: when I came back I wondered what I was going to write about this because I reckoned that Schweitzer had feet of clay, but at the same time there were millions and millions of people all over the world who'd never seen him, had never been there, who nonetheless were, perhaps, living lives based on better values, thinking in more decent racial terms because of the example, the public example of Dr. Schweitzer, what business had I got to go and suddenly destroy all this thing when it was really of very little importance, the disadvantages he was bringing to a few thousand Africans in the Gabon was of less importance than the enormous advantages he was bringing to millions of whites and Europeans and Christians and Jews and everybody all over the world. So the consequence is I wrote about nothing, until he was dead and it has to be remembered, you know, when you say that I was an iconoclast, with Albert Schweitzer, when my book came out and there was this chapter about Lambaréné, Schweitzer had been dead three years. There was no danger of then destroying him, and furthermore I would have laid myself open to the most intense criticism of being a nosy journalist who merely capitalizing and sensationalizing on the destruction of an image that had meant a great deal to many, many millions of people.

Studs Terkel I think--James, could we stick with this for a minute. Here are you, a remarkable journalist, and you go there and you expose what is a lie, you find was a lie, you hold off on it until the man, the saintly figure who was far from that--

Studs Terkel But in your mind is maybe the myth, phony though it is, can make the others behave better than they may because of the myth. You know Eugene O'Neill's "The Iceman Cometh"?

Studs Terkel When the Iceman cometh, the guys' lives are drab and dull and they live in fantasy and they sleep, and along comes Hickey and Hickey means well, and Hickey says, "Face the truth," and slowly destroyed them. You were afraid you might be Hickey at that moment.

James Cameron That's right. I didn't want to be Hickey. And also, of course, "Iceman Cometh", one of the miserable characters in the mise-en-scene of that particular play was also called Jimmy Cameron.

Studs Terkel I didn't realize that, just occurred to me, Jimmy Cameron, James Cameron is my guest, I'm his guest at this moment here in Portland at Lewis & Clark College, Jimmy Cameron. I hadn't thought about that.

James Cameron Well, it isn't the function of a journalist to go around this trying things just because it is amusing to

Studs Terkel But wait a minute, it wasn't, see--I've got to ask you about this, or challenge you. I don't know. You didn't do it, you waited until later, but the fact is, you have done it in other matters. The myth of a little patriot Syngman Rhee, a phony little brutish dictator and mass murderer, just as Thieu, a pretty good guess is that, and we were [building?] you did that then, you know, against all the odds. You visited North Vietnam and you spoke of the American bombings, the first Western journalist to be there, the uncommitted one to see it, you've done these, you upset the apple cart so many times, but in Schweitzer's case you felt there was a myth that should not be disturbed for a while.

James Cameron I thought I couldn't see the case are in parallel at all. The Syngman Rhee isn't the big politicians and the big political leaders are in a different condition all together. They themselves exercised power, you see. Schweitzer did not exercise power except very, very indirectly. And insofar as he did exercise power, it was a beneficent power, it was a good power at the remove of many thousands of miles. It was a beautiful power and it was a splendid concept. And I liked the concept, because that's why I went there at a great cost of energy and time, because I thought it was a magnificent concept and I still think it was

Studs Terkel At the same time in your autobiography, you point out that he basically is a patron of the great white father and at deep, deep bone, deeply a racist, you see.

James Cameron Oh, very much so, but I don't think it matters now, when the Schweitzer cult is over anyhow, and in justice to myself I have to point out that I wasn't conned by Schweitzer, but I didn't want to do it at the time, and I waited for many years.

Studs Terkel So now we come to your other adventures and your discoveries. You also now became a close friend of Nehru in India.

James Cameron I did indeed. I met him in the days of the original negotiations for independence in 1946 in India and he became, I am obliged to say without conceit, that he did become a friend of mine. And I considered him, and as I consider him to this day, as being the most significant and important political figure I've ever met in my life. And a lot of that may, of course, well be subjective judgment because he was very personally kind to me. He would give me time when other people wouldn't give me time, he would instruct me in all manner of Asian methods of thinking that I was not aware of. He took trouble, and therefore I just loved him very much indeed, he was a sort of father figure to me, very much so, indeed. The relationship is very hard to describe I'm probably a bit romantic about Nehru, too, because he died too late, you see. He should have died four or five years before he did. He clung to power too long and he made some tremendous errors. But after independence in 1947, '48, '49 and '50, he had this dream that the third world could in fact be created to stand between two great big powerful worlds of the Communists and the Americans. And the third world, which after all greatly outnumbered in people, all of them, could be done with the innocence of newly independent countries and with the political background and knowledge and historical perception of the British. And this was my great dream, too, you see. We talked over it, Nehru and I, many, many times, the third world could become stronger than the Communist world, stronger than the American world simply because a) there are more people involved, and b) you have a quality that is more infinitely more important than nuclear weapons, which was the quality of truth.

Studs Terkel So this was that, that moment in your life. Perhaps, would you call that one of the exhilarating moments in your life?

James Cameron Oh, yes, I really would, yes. You see, whenever I think of the of the disenchantment that everybody now has with politicians and politics in general, which I'm beginning to share, it's very different not to, of the whole system, the whole machinery of politics is becoming contemptible, that it wasn't always that, because there was at least one man to whom it had a real and genuine meaning, and that was Nehru.

Studs Terkel Nehru. Well, this is the parenthetical question, yet it has to be asked. India; China; differences; Nehru; and now, women. Two women, or three women. His daughter, Indira Gandhi, Golda Meir, and Madame Bandaranaike of Ceylon.

James Cameron And it is a very curious paradox that the three countries of which the three women are preeminently leaders, Mrs. Bandaranaike, Mrs. Meir and Mrs. Gandhi are the three countries and the most distressful situation, all three of them are suffering from tremendous hardships and political tensions one way or another. I think this is purely fortuitous, it's nothing to do with the fact that they are women, it just is the case that such has happened. I am, I know Mrs. Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, very well, indeed, because I knew her 20, 30 years ago when she was quite a young woman, and was acting as the hostess for her father as she always did. I am not altogether sure that I approve of dynasties, and there looks as though there's a narrow dynasty being created in India as a Kennedy dynasty has tried to be created here in the United States. I think if you have the non-heritable system of democratic elections, you should not necessarily create dynastic privileges to go with them. On the other hand, Mrs. Gandhi has done as well in her circumstances as anybody else could have done. But I, you know, I think republics are republics. Monarchies are monarchies, and never the twain shall meet.

Studs Terkel Well, thinking about yourself now and the variety of journalistic works that you've done and sensations, not that you intend to create sensations, but that you did. Finding out truths and speaking about them, holding off on some, and then coming to the man you left, Beaverbrook. Now, he was furious when you quit. You quit because you felt it was unfair journalism, though it had nothing to do with you. You quit. Now years have passed, this time you've traveled to various countries, you've worked as a journalist, and you get a call one day from Beaverbrook some 13 years after you left him

James Cameron Oh, yes. I got several calls, but every time I believed that somebody was putting me on, you see, because I knew that Beaverbrook disliked me so much that he would obviously never call me at all, so every time he called up I hung up on him, until one day a man in a black suit turned up at the door and said, "In five minutes' time you're going to get a telephone call from Lord Beaverbrook, and please will you pay attention to it, because it is Lord Beaverbrook, and I am here to see that you take the call." So it was Lord

Studs Terkel This is how many years after you left him?

James Cameron Twelve.

James Cameron I'd never seen him since, never heard of, we'd had no communication at all, but in the meantime I had written a book about the First World War called "1914", which was about the social causes of the First World War, it was a pretty rotten book, I must say. Anyhow, Beaverbrook came on the phone and said, "Well, how are you?" in his usual way, just as though nothing has ever happened. "I read your book. It's a very bad book, you see." I said, "Yes, it is a very bad book." I [unintelligible] Pavlov's dog when Beaverbrook barked, I salivated, you see. And he said, "Well, I've got an idea

Studs Terkel "-- You mean, you salivated, but you also told him off, too.

James Cameron Yeah, but what happened was, he said, "Well, will you come to dinner?" So I said, I was about to say yes, you see, at once, and then I remembered that in the days when I'd been working for him, he was always calling me up and say, "Come to lunch, come to dinner," and it would always turn out that I was in London and he was in Montego Bay in Jamaica and it would entail an enormous trip through [Canada?] across the Atlan--just to go to lunch. Hell of a long way to go to lunch and then back again, so I said, "No, no, no, well, now, first of all, where are you?" You see. "Oh," he said, "Just around the corner, just in the Riviera, at Cap D'Ail, by Nice." Well, I must confess I was so full of curiosity I couldn't wait. I knew that there would be nothing to my advantage at the end of it, but I was so interested to know what he could possibly want with me, so I went, and he sent an airplane for me Well, to Nice and then to his house down at the end of the Riviera. Called Cap D'Ail, beautiful house. And when

Studs Terkel

James Cameron and Where Well, to Nice and then to his house down at the end of the Riviera. Called Cap D'Ail, beautiful house. And when we got there, the business he had to transact with me was very, very minimal indeed. He was all in favor of people writing books about World War One, but not from 1914 because it wasn't 1916, you see, that he himself, Lord Beaverbrook, has come onto the big political scene and become the great sort of political catalyst between Lloyd George and Winston Churchill and so on, and would I not think it a good idea now to write a book about 1916?

Studs Terkel Meaning about Beaverbrook.

James Cameron Meaning about Beaverbrook. Well, I said this might be a subject for discussion, and we left it at that. But then said Lord Beaverbrook, "Well, you'll stay for dinner, of course." Well, since it was already six o'clock at night and I was in Nice, I didn't see there was any alternative. So I said, "Thank you very much. I'll stay for dinner." Then he says, "I'm having a party for you, you know." So I said I didn't expect you were having a party for me." "No, it'll just be four of us," he said. So I said, "Who are the others?" "Oh," he says, "Aristotle Onassis and Winston Churchill." Well, my God, I've never met either of them, you see, what an extraordinary situation this is going to be. So anyhow, we were sent up to wash our hands and faces, and I came down a little earlier than anybody else and I get a telephone call. The butler comes in with a very set face and says, "Mr. Cameron, will you take a telephone call from the "News Chronicle"?

Studs Terkel Which is the opposition paper.

James Cameron Which, of course, was his opposition.

Studs Terkel The one you were, you were working for the "News Chronicle" at the time, the opposition paper of your host, Lord Beaverbrook.

James Cameron That's right. And I said, "Yes, well, what's it all about?" This was the editor of my paper. And he said, "Well, Mr. Harold Macmillan, who was at that time prime minister, has just called a meeting of the British editors into Number 10 Downing Street, and he said that he's off to Africa tomorrow," where he was going to make the famous "Wind of Change", speech, but he feared that he would probably have to return within the next very few days to attend the funeral of Mr. Winston Churchill, who had just suffered a very grievous stroke and since he had suffered his stroke down in Monte Carlo in the hotel owned by Aristotle Onassis, which was just down the road from me, would I keep an eye on this situation. So I felt in a very, very equivocal position indeed. But I said, "Well, I'll keep an eye on it. I can't guarantee anything more than that." And before the phone had even been put back on the hook, the door opened and three footmen came in, bearing the lifeless body of the late prime minister, Mr. Winston Churchill, dead as a duck, obviously, lolling, pale, unconscious, and I thought, "God Almighty, he's died on the doorstep. Now what am I going to do? How am I going to get this story back to my newspaper? I have been present at the death of Winston Churchill." And I'm trying to telephone it from the house of my newspaper's greatest opposition. "I will never get away with it. I'll be put in a cellar. I'll be shot. I'll be thrown over a cliff." All manner of things.

Studs Terkel By the way, didn't Beaverbrook try to clobber you once?

James Cameron Oh, yes, indeed, he tried to kill me with a champagne bottle, was better than a bottle of beer, I suppose, but anyhow, while I was mulling over these grievous thoughts because I was in the house of one gangster having just observed the death of another gangster, and what was I going to do about it? And fortunately for me at that moment this lifeless body of the late prime minister Mr. Churchill started to twitch and stir and wriggle. So I realized that he wasn't dead after all, but was mainly being carried in because he was unwell, shall we say. And anyhow, that was how the evening proceeded. Mr. Winston Churchill, whom I had never met personally in my whole life before and it was a great tragedy to me that I should have to meet a man whom, although I didn't altogether admire him, nevertheless was one of the signal figures of contemporary times. And I had to meet him in his dotage because he sat at table and uttered never a word from beginning to end of the whole thing, but slumbered gently throughout the whole proceedings while Beaverbrook and Onassis talked across him as though he were already dead. That poor old guy, you

Studs Terkel And what did they talk about?

James Cameron They talked about money and nothing else. There was nothing else they could talk about, you see. And only one thing did Winston Churchill say. When he roused himself from his reverie, he climbed out of his slumber and suddenly interrupted them and said, "Max!" to Beaverbrook. "Max, did you ever go to Russia?" And Beaverbrook said impatiently, "Well, of course I did, you know that very well. When you were Prime Minister you sent me there as minister of air production. I was sent on the mission to a Stalin. Don't you remember?" "Ah, yes," said Churchill, "I remember sending you. But did you ever go?" And then he relapsed back into his comfortable twilight from which for the entire rest of the evening he never in fact--

Studs Terkel Did he have the Romeo and Juliet cigar and the Courvoisier?

James Cameron No, he didn't. That was a little later when he was wheeled into the living room where Beaverbrook and Onassis continued their tedious discussion about stock markets and all these things that I couldn't join in because I didn't know anything about it. And then Mr. Onassis, who was Churchill's host, fetched out an enormous foot-long cigar, rammed it into Churchill's mouth as you would put a dummy comforter into a baby's mouth, and a sort of ritual gesture that the old waxwork was not complete without his final prop, you see, and he lit it. And, of course, it began to slip from Churchill's lips and it began to burn his shirt front and I was sitting beside him because strangely enough, he and I were the two silent people in the whole thing, he because he had nothing to say and I because I knew nothing to talk about. And I said, "Excuse me, sir, I'd better take that away before you set yourself on fire." He said, "Thank you very much. Thank you very much." And I did, and I was hardly burned at all, so I put it quickly out and I stuffed it in my pocket and I thought, "Well, this I'll have to give to my son who's at school who'll get a tremendous amount of face from this, the last cigar Winston Churchill ever smoked," you see.

Studs Terkel I'm thinking of that scene, remember reading it in your beautiful autobiography, "Point of Departure", and I thought in reading that scene you're describing Churchill, whose political ideas you disagreed with, you--were the opposite of what you believed in. And I see there's some color, and these two very dull men who were at that moment powerful as he was impotent, I thought of a comic "King Lear", a passage of power from a colorful Neanderthal in a way, as he was, you know, in the 20th century, though Henry Luce's "Time" made him man of a half-century, since he'd given us Mahatma Gandhi and Albert Einstein. At the same time, the two dull plastic figures, you know.

James Cameron It was a "King Lear" situation, what should have happened was Churchill should have arisen at one point and struggled to his feet and said, "Howl, howl, howl."

Studs Terkel But this is part of your life. There you are, observer, Beaverbrook for reasons of his own, asked you there, and you're there at that moment, you know. Again, you find earlier, during our earlier conver--you spoke of irony and absurdity, again, irony and absurdity, and power and impotence and the passage so quickly, too, is apparent, isn't it?

James Cameron So very, very quickly. It's probably a good thing. If power endures too long in one central power it becomes probably institutionalized as part of--

Studs Terkel We have a fourth program coming up, I know, because it involves other incidents in your life. Meetings with Castro and with John Foster Dulles, strange though this combination may be, they're not a combination by Cameron's encounters and a certain event, adventure of yours in Albania. Before the American recognition of China, Albania did, and that, but something here, power going quickly, but the development that hits me in a sad sort of way, natural, is that the dullness, suddenly the power is now rather dull--power was in the hands, always brutish men one way or another have had power, brutish man of some flesh and blood, horrendous though they be, and how plastic figures.

James Cameron That's right. You see, and while, as you properly point out, there was a great deal of Winston Churchill's politics with which I not only disagreed but thoroughly, bitterly disapproved. At the same time, there was a man. There was no plastic man at all. There was a human man, and furthermore, a man capable of a brilliant conception of phrase, a brilliant--he didn't employ speechwriters, you know. He didn't have to have somebody sending in a draft of his speeches. He did them himself, and his persona may have been outrageous in certain respects and his political attitudes may have been odd by my standards, but at the same time, he was no dummy. Think of his successors who succeeded--I mean, really. This is not be too personal about it, but think of the ventriloquist's marionette that we've got now.

Studs Terkel I think of Reagan. I think of Agnew. I think of Brezhnev, too, you see.

James Cameron Of course. Oh, yes.

Studs Terkel And then we have to think of Onassis and Beaverbrook and of the dullness, the drabness, this is the point, you see.

James Cameron The only subject of conversation was money, you see, it was the only thing, and not just money what you can do with money, but how you can get money, and I always have been very interested in how you should spend money, because I've never had enough of it to spend. I've always longed to think of how you would get rid of money. But they were not interested in that, it was how you acquire it, was the only thing that bothered them.

Studs Terkel So it's acquisition thing.

James Cameron Oh, acquisition.

Studs Terkel Acquisition of thing.

James Cameron Not disposal of it.

Studs Terkel So there you were, perhaps we can end this third hour and the fourth hour will be coming up, the third hour with James Cameron, that event with that funny, sad, clownish burlesque. Serio-comic tragic dinner. Probably Churchill's last dinner, I suppose, with others. Churchill and Onassis and Beaverbrook and you, James Cameron. A thought, perhaps, just a reflection before we end this hour.

James Cameron I think the thought was that once again, as was always my lot, I got in always on the third act of history, that it was a shame. I shall always think of Churchill now as a baby, as a little infantile baby being carried around by three men from place to place. I don't think of him now as "We shall fight on the beaches." And yet, you know, he's not forgotten. Only ten days ago I was watching on the television here, and I heard Richard Nixon making a speech in which his peroration was, "And history will say of America that this was our finest hour." And I thought, "Hello, I must have heard that before somewhere. That, wait a moment, did I--it was a, it's a good enough phrase when Winston Churchill first used it, and it's good enough to repeat. And then I analyzed what he was talking about, he was talking about meat prices. He was talking about the price of steak. And because he was going to put a ceiling on the price of steak, that was America's finest hour.

Studs Terkel But the previous time he plagiarized Churchill's finest hour was about Vietnam. He spoke of that as its finest hour, as America, United States' finest hour, too. So we have sort of a an obscenity occurring here as far as language, perversion of language, and about subversion of thought, don't we? Maybe we can end on that note now, the use of language and thought, and how the banality of language and the banality of thought sometimes hand in hand.

James Cameron Yes. Well, of course they do. And if you are going to make your great public announcements in the words of employees and menials who are sitting in the back room feeding them up to in separate takes, then how can you expect inspiration to come from your words and how can you convey inspiration to your people?

Studs Terkel We're coming back to standards that would be that of a political leader or a journalist such as James Cameron. I know the last phrase for now: Age. You think of Churchill as a baby. This man of so much power. Called the man of the half-century, but there's someone else who lived to an old age whom you knew and I was fortunate to meet one day, and that's Bertrand Russell, also age. Both died roughly about the same time. Churchill survi--Russell survived Churchill a bit longer, but they were contemporaries, and yet, how different.

James Cameron Yes. And Russell's brain, of course, survived Churchill's much, much longer. Churchill died mentally and intellectually six years before his body died at all, which was a great pity, but it was not his fault. Russell's brain remained active and vigorous to the very last. I don't think his judgment did. Frankly, I think he made some silly errors of judgment later on, as is permitted to a man of ninety-odd years who has contributed so much. He is allowed a few failures and flaws in his 90th year, for God's sake. But at the same time, when he died, he died like that, thunk. He didn't die by stages like Churchill did.

Studs Terkel You know, I'm thinking the last time I asked, at the time I saw him, it was the only time, he was about 90. And just that I thought of the vigor, it was during the Cuban Missile Crisis, perhaps he was 89, and the time I saw you, too, and we were talking earlier, maybe it was the second hour, couple of days before, about the spirit of youth. You know, that chronology and I do with it, as we're talking now, this conversation's about two weeks after Picasso's death at 91. You think of Picasso, of Bertrand Russell, of Pablo Casals, who was alive, or Charlie Chaplin, or Bernard Shaw who died at 94, of Sean O'Casey.

James Cameron Yeah.

Studs Terkel And somehow the spirit of youth and creativity.

James Cameron I had lunch with Charlie Chaplin only three weeks before I came here. In England. Strange old man, too. But, great men. Great men. All great men, in their way. Churchill, Russell, Charlie Chaplin, Pablo Casals.

Studs Terkel Picasso.

James Cameron Picasso.

Studs Terkel But I'm thinking about that--something--call it youth, call it boyhood, call it child, not childish but child-likeness, the wonder, this air of wonder about them, like I might say this, by the way, about James Cameron.

James Cameron It's endless rebirth every morning. You start again every day. You don't die a little every night, you start again every morning.

Studs Terkel Now, that's part three of a conversation with James Cameron.