Heinrich Gruber and Howard Schomer discuss Nazi Germany and resistance

BROADCAST: 1968 | DURATION: 00:18:13

Synopsis

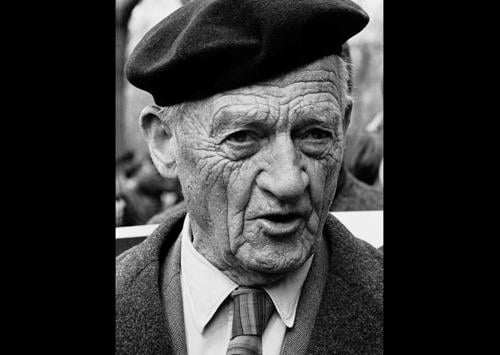

German theologian Heinrich Gruber and pastor Howard Schomer discuss Nazi Germany and resistance

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel It was just a few moments ago I suffered what may be described as a profound experience in hearing Dr. Heinrich Gruber, who I suppose is one of the unsung heroes of our particular century, a benighted century in some respects, and I would hope enlightened. Thanks to my good friend Dr. Howard Schomer, president of the Chicago Theological Seminary. Before we talk with Dr. Gruber, perhaps, Dr. Schomer, if you would tell us just a bit about Dr. Heinrich Gruber himself. I know that many of the listeners are acquainted with Rolf Hochhuth's play "The Deputy," and there's a rather interesting footnote in his sidelights.

Howard Schomer Yes. In the second edition of "The Deputy," Hochhuth puts a note saying, "I have learned, since this play first appeared, that the dean of the Protestant churches of Berlin, Dr. Heinrich Gruber, tried, as does the hero in my play, Riccardo, tried several times to be put by the Nazis in the ghetto and dealt with, as were the Jews. This Protestant Christian leader would not be put into the ghetto, the Nazis didn't do that. Instead, when he tried to enter into one of the camps for the Jews, they immediately arrested him and sent him to Sachsenhausen where he spent most of the war years, atrociously treated, his teeth kicked out by an SS man, experiencing the kind of thing that we all have read about, as a religious leader who would not bow the knee to the Hitlerian racist guards."

Studs Terkel You spoke of Dr. Gruber in introducing him before members of, you brought up associates of the seminary, as "a west-running brook," just a phrase, why you use that Robert Frost

Howard Schomer I've always been fond of Frost's vision of some little nonconformist New England stream that prefers to flow into the Gulf of Mexico instead of into the nearby Atlantic. And my friend Dr. Gruber is just such an individual. It would have been easy to go along with, to run along with, the majority opinion in Hitler's Germany. He preferred to go the hard way because it was the true way for him to go, the way of resistance to totalitarianism in the name of the common humanity of all God's children.

Studs Terkel Dr. Gruber, I deliberately asked Dr. Schomer to tell the audience about you so we know, have an idea who you are, or what kind of man you are. You were speaking of "The Deputy," Rolf Hochhuth's play, "The Deputy." And since you are mentioned by Mr. Hochhuth in the play, and are deeply involved personally in every way with this play and the meaning of it, you were saying it is more, that it is not just the responsibility of a vicar of Christ, Pius the XII. It is far, far more than that. Would you mind explaining that a bit?

Heinrich Gruber I say always that Christ, the [charge? chart?] of Christ are clearly and are spoken in the parable of the Good Samaritan. The priest and the Levite who go back are guilty in the judgment of Jesus Christ. Every one who is silent to injustice is also guilty. Men who speak and not to injustice or is too long silent is likewise justice. And that what -- Is what the play will show. It will say, that we have not the right to be silent if we see injustice and inhumanity and I myself, I have been silent very often. I am feeling the guilt of this silence and of my inactivity and ought what I have done little to help people and to speak and to all to my suffering cannot put away this guilt which I am feeling.

Studs Terkel Well, Dr. Gruber, and Howard, please enter the conversation, too. You spoke of the guilt that all men who are silent when something unjust occurs as in the destruction of the Jews by the Nazis for one, yet you spoke of yours -- You were in a concentration camp and you spoke of your guilt being silent then and watching, I remember you spoke of Russian prisoners of war being murdered, but then a listener during the luncheon who was a also a concentration camp inmate formally said, "Isn't there a difference between the silence of an inmate whose life may be at stake and someone outside, in this instance say, Pius the XII?

Heinrich Gruber No. I think that every silent is a guilt. In concentration camp and freedom. And if we are in freedom, we have more possibility to speak. But as that is my opinion, since the witness of creed and of love is more important than our personally life.

Howard Schomer Well, I'm sure that the man who spoke up so vigorously in the discussion out of his own suffering in a concentration camp and his own memories of silence that he had to observe, does have one point I would hang on to, and that is that silence is more costly and speaking is more costly to some people than to others. This is why I feel, for example, no inclination, and I know Dr. Gruber doesn't, either, to accuse the pope in Rome, Pius the XII, for his particular silence during the Nazi period. He occupied, as you said, I believe, Dr. Gruber, a position of such extraordinary responsibility that if he had spoken out, it could have worked either of two ways: It could have brought down with the madman Hitler and his regime lightning and thunder upon still more hundreds of thousands of people, and we have the advantage of sitting now after the event looking backward after the Nuremberg trials, after the full revelations, and judging that if he had spoken out, perhaps it would have diminished the number of lives of Jews lost at Auschwitz. We can't be sure of that. And he could not be sure then, if he had spoken out, whether more or less people, the Catholics as well as Jews, would have been given the same treatment. So I suppose that the man in the concentration camp certainly does not have the kind of public responsibility. Only his own life, probably, will be wiped out if he opens his mouth. The Pope in Rome, any other person in high responsibility involves hundreds of thousands of people.

Studs Terkel Isn't this, but on this point, Dr. Schomer, Dr. Gruber, weren't you saying that you yourself had a personal feeling and opinion, even though that's conjecture as to which way it might have gone, had the vicar of Christ spoken out at the time?

Heinrich Gruber Yes. I mention example of my own silence, even the concentration camp Sachsenhausen, thousands and thousands of Russian war prisoners have been murdered. I and many of my comrades has been silent, not because we think that we are near by death but the SS murderers was in a bloodthirsty frenzy and we think if we cry out that it's murder, not only we are murdered, but all the many of our comrades, and therefore we remain silent. But now I am feeling this silence and later also as a guilt and I cannot say I saved a thousand Jews and have helped so many people and therefore I am without guilt. Guilt can only be forgiven by God, andnot by compensate with our good works and good deeds.

Studs Terkel I follow that. I don't mean to belabor this point about the guilt in Hochhuth's play of the pope being silent, because he himself says, Hochhuth says somewhere in the notes toward the very end, you remember, Howard, about fence-sitters generally. It's over and beyond one person's guilt. Hochhuth is speaking of the guilt of silence under any circumstances, isn't he?

Howard Schomer Yes, and I think that the experience of my friends in the German churches during the Nazi period amply demonstrates that the neutrals, the fence-sitters, are the most guilty of all. In a sense, the people who do the wicked things, in some sense, are doing what their distorted consciences dictate that they should do. Even as the tiny minority which resists injustice and unrighteousness at whatever cost, like our brother Gruber here, are following their consciences. But the people who try to find some area of neutrality when there is no neutrality, when you are either for or against human values and God's law, these people are the guiltiest, it seems to me. And I think this is where it becomes painfully applicable to the American situation today, don't you, Dr. Gruber?

Heinrich Gruber Yes, and I have always said, "Guilt is not only about we have done, also the good we have not done." Understand?

Howard Schomer Yes. Every time we have omitted to do what we ought to have done, this is truly a guilty omission, as a guilty action might have been. But, what were you saying before in the roundtable discussion, about the racial situation as you see it today in the United States? We are here as Christians, not as nationalists. It doesn't matter that you're a German, and I'm an American. We want with your experienced eyes to know what the American racial tensions dangers and prospects look like, for you can see it in a perspective that almost none of us here, out of personal experience, could possibly have.

Heinrich Gruber I say always the greatest injustice is that one believe that he can divide humanity into those of superior and inferior worlds. What we since -- What we once in Germany did, to have to do against the illusions of Hitler, are we now once again experience in huge measure in your country one believes he is able to designate people as second-rate because of their derivation and skin color. We search anti-complexes hate and revenge feelings. It alls begin and with Auschwitz and Majdanek it all ends.

Studs Terkel And of course this powerful comment I remember Dr. Gruber making at the roundtable. Howard, Dr. Schomer, this point of, as you say, is not altogether analogous, yet there's a strong parallel. He spoke of the anti-complexes, the anti-complex, whether it be anti-Jew in Germany and then the Nazis, or at this moment anti-Negro and many feelings, even even unconsciously held. Do you feel this, Howard, since we're coming close to what you call "the summer of decision"?

Howard Schomer Yes, it strikes me with ever-greater force that perfectly ordinary American white people have grown up, as I did, with good parents saying to them when they were very small and happened to notice that all the Negroes lived in one section of town and that the streets were dirtier there and the houses were more dilapidated there and there seemed to be more people on the streets at hours when other white people were either at school or at work, I say many American whites have learned as I did as a little child, "Well, that's the way they like to live." In perfectly good conscience from generation to generation, American whites have looked at the Negro population living obviously on a lower economic and cultural plane and said, "Well, that's the -- Some people are like that." And dismiss the question. And so our silence became a massive social silence of acceptance, as you say brother Gruber, of two classes of people: first-class accommodations and first-class aspirations for those who have first-class color, namely white. And second- or third-class accommodations and all the rest for those who happen to be slightly darker or a good bit darker.

Howard Schomer Since Eichmann trial I am feeling such a great danger in our time is to work and to speak with anti-complexes, and men who work with anti-complexes remain in a state of negation, of hate and rejection, and lose all moral connection and that is a great danger before which we are once as standing and for which you are standing now in your country.

Studs Terkel The parallels you can't get away from, the incredible parallel that is here as as we listened to Dr. Gruber this afternoon, his own experiences as we think of the play of Rolf Hochhuth's "The Deputy," I know Howard Schomer and I, as Americans living here, think immediately of a situation here. This parallel is not a false one.

Howard Schomer Oh, it was very striking, you know, when Dr. Gruber said that often during the Nazi period he felt that if all of the preachers, all of the deans and university presidents and notables of the society would on one Sunday morning, by quiet concerted plan, wear the gold, the yellow star, the yellow star that Hitler inflicted upon the Jews to identify them

Studs Terkel As King Christian did in Denmark.

Howard Schomer As King Christian did in Denmark. Very good. That this could have had a revolutionary effect on the public opinion that wanted to believe there were two orders of humanity, one an "Untermensch," a sub-human being and the other a racially superior "Lord of the Land." Well, what are we waiting for in this country? We have to have some way of identifying the massive white population with a cause of racial equality. We can't all be Black in the way that a certain novelist made himself Black, but I'm glad that a lot of people in Chicago today preparing to demonstrate publicly in favor of the civil rights bill before the Congress, in favor of more sensitive handling of school opportunities by the school board and the city authorities of our own municipality, Chicago, are donning the funeral band, the Black band, not the yellow star, but the Black band around their arms. I hope they will be hundreds of thousands and not consider themselves far out at all but consider themselves acting in the highest tradition that the great religions have always tried to teach and to demonstrate.

Studs Terkel As you're saying this, this is a positive act, non-silence speaking out. I'm aware, too, of other engagements on the part of both Dr. Schomer, has to catch a plane, and Dr. Gruber has to go downtown. I hope, before we just close now, I hope that very soon the three of us can meet again when Dr. Gruber comes through, there's so much of his story that must be so important for us in America to know, not as a question of looking at Germany from the outside and saying, "Ah, guilty," but looking into ourselves. I know you

Heinrich Gruber And not only looking at the past, but only to looking for the duty for the present and the future. That's a great question.

Studs Terkel Just this last point that Dr. Gruber made, Dr. Schomer as I say goodbye to both of you now,, and thank you. He says it begins with a feeling, just as it began there, of superiority toward one people, or hate toward one people, and ends in Auschwitz or Majdanek. This then, I suppose, is our moral.

Howard Schomer Right.

Studs Terkel Dr. Howard Schomer, thank you very much. And Dr. Heinrich Gruber, it's been a privilege and we shall continue in the future.