Drs. Quentin Young, Lambert King and Robert Maslansky discuss public hospitals in the United States

BROADCAST: Apr. 26, 1976 | DURATION: 00:53:42

Synopsis

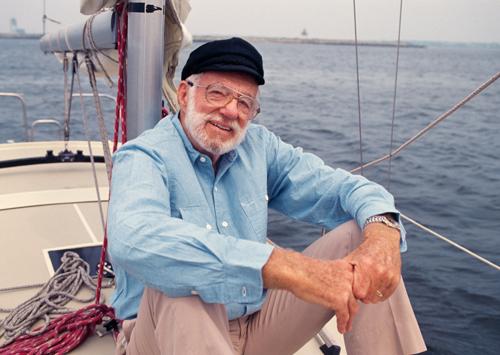

Drs. Quentin Young, Lambert King and Robert Maslansky discuss public hospitals in the United States. Young is the chairman of the Department of Medicine at Cook County Hospital, King is the medical director of Cermak Memorial Hospital, and Maslansky is the director of medical education at Cook County Memorial Hospital.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel We hear much talk about the public hospital, Chicago Cook County Hospital, and the program this morning, with three doctors, will not concern the case of Quentin Young versus the governing board of Cook County, that is in litigation. Rather, we're discussing a much, much broader subject: the role of the public hospital in the United States. Its history, its current status, and what future does it have. And around the microphone is Dr. Quentin Young, who is Chairman of the Department of Medicine at Cook County, Dr. Robert Maslansky, who is Director of Medical Education at Cook County Hospital, and Dr. Lambert Young (sic), who is the Medical Director of the Cermak Memorial Hospital which is part of the Cook County Prison Service.

Lambert King Lambert King, of course.

Lambert King Yes. Not Young; he's a close friend, but no relation.

Studs Terkel Lambert King. Okay. So it's King, Young and Maslansky in a moment after we hear from this message. So, okay, the public hospital. Chicago has one: Cook County.

Quentin Young Yes, Chicago has one of the proudest. Those of us who trained there would say it was the best. And that sense of pride and competition is probably the first point of understanding the public hospital. When people who trained at Cook County get together, and that's a large hunk of all the doctors in this country, even if they never knew each other before, after introductions and identifications they talk about County the way one would talk about a great school, a great country, a great friend, a great mistress, maybe, because County was, perhaps, all those things to us.

Studs Terkel Were you a County alumnus of one form or another, Lambert, Dr. King?

Lambert King Yeah, I did my internship and residency there between 1971 and '74 and have remained there on the staff, as part of the attending staff.

Studs Terkel Dr. Maslansky?

Robert Maslansky No, I came there by desire, having heard these stories.

Studs Terkel It's a public hospital. The word in the mind of me, I'm a small child. I'm a boy. Let's say I'm 10 years old. Public hospital. First impression is, something out of Charles Dickens' day, a charity hospital.

Quentin Young Well, it's just right. The history of the public hospital in this country is not too different from that of its European precursors. It was the place for the sick poor to be taken care of. We have to remember the role of the hospital in general has changed dramatically over the past century. It used to be a place to go to die. A respectable person wouldn't go to a hospital because the poor weren't respectable. These hospitals were so created. Such is the charter of Cook County Hospital. The hospitals changed mightily over this century. And right now we've come full circle and it is unrespectable not to die. Disrespectable, I guess, is the right word, not to die in a hospital. We can talk about that because it has profound cost and social implications, but the public hospital has this particular history in this country. It's a medical system that more so than anyone in the world has been dominated by what we call private sector. Now, the public hospital, therefore, got what was left out. It turns out that, relating to the major cities of this country, proud institutions grew up. Some of the names are familiar even to people outside the medical field: Bellevue in New York, Charity in New Orleans, Los Angeles County, San Francisco General. I think those are names we recognize. Not so familiar are places like D.C. General, Detroit General. We go on and on, a whole array of public hospitals for this purpose.

Studs Terkel Now what's happened? The public hospitals then grew in number as well as in attendance through the years. Bob Maslansky?

Robert Maslansky Well, they not only served the community, the sick poor of each community, but they also served as training grounds for several generations of physicians. I would imagine that fully half of the doctors in this country have done all or part of their training in public institutions. Quentin, didn't somebody estimate that 10 percent of all physicians practicing now had had some relationship to Cook County at one point?

Quentin Young That would be a minimum figure.

Lambert King That's in this country.

Quentin Young When I was in training, yeah, it was as many as 20 percent, but you're absolutely right. Far disproportionate to their portion of the beds or portion of patients, they have been the training ground for--

Robert Maslansky Well, you asked what's happening. Some very special things have happened in medicine in general. The ways of serving people have changed appreciably in the last two decades. The economics of serving people have changed appreciably, and I think all of these are intimately tied up in what has happened to the public institution.

Studs Terkel Isn't one of the questions--by the way, we can come in now, you know, Lambert King or Bob Maslansky or Quentin Young, you know, need not wait, you know. No protocol involved here. The subject of training grounds. Some would say, "Hey, wait a minute. Are these people"--here's a poor woman coming in, or "Someone experimenting on me? Some young doctor, male or female experimenting on me?"

Quentin Young And well said. I trained at County before my two colleagues here were out of swaddling pillows at the end of the '40s, early '50s, and while we did an awful lot of care to a lot of people who weren't going to get it any other way, absolute candor demands that one of the functions of that institution was to train all the young doctors and medical students in this town. Likewise, it has to be said, happily it's a chapter that's closed, what would be called the human experimentation approached vivisection. Informed consent would be something like, "Hold out your arm, I'm going to shoot this material into you." A whole lot of social and political events have made that a dark closed chapter. In our place, for example, the highest priority and the sternest disciplines relate to how you treat those patients. When medical students come on our wards, they have to, in the Department of Medicine they all have to have, like it or not, an orientation by me. The whole message is, these patients must be treated with dignity. And the one way to be kicked off our wards is to not call them Mr. or Mrs., or in any way fail to respond to their concerns, including their unwillingness to be examined, they have to give consent. They change their mind, that's fine. It's very important.

Robert Maslansky No, I simply wanted to make that clear. We have a committee structure that provides for any issue having to do with the protocols of experiments done. And it's meticulously reviewed by, and very carefully by, not only group of physicians but lay people as well, as to the appropriateness and humaneness of any work that we're doing.

Studs Terkel Now, is this, now, this development that's taking place, the social awareness, particularly on the part of doctors such as yourself, members of the staff and those in charge, too, such as yourself. Is this happening in other hospitals, too, in other public hospitals, in other cities to this development?

Quentin Young My view would be that there is a kind of a frontal way, because the way it's evolved is that the people who choose careers in public hospitals, now that there are many other places where you can train, first-rate places in the private sector, differentiate. And these are people who, I think, broadly speaking, are trading off certain things. They're trading off, perhaps, a higher level of income and a certain kind of ambience that's more like the Plaza than Skid Row. And what they're trading it for is an extremely rewarding situation where almost anything you do is helping somebody.

Studs Terkel It's almost pro bono medicine, then, like [does it go?] all the way.

Quentin Young Large element of that. It's a place where you have a camaraderie at the very best of people who feel that they are the court of last resort, and that concept that, unless you're a very sadistic person, you can't but do good, obtains in a place like County and the public hospital, because what you see there are the end products of a tough, cruel, alienated society, whether it's the junkie who has bad hepatitis or the neglected pneumonia or diseases that should be on the junk heap like tuberculosis, they're still problems at Cook County Hospital.

Studs Terkel And what's your experience been, Dr. Young (sic)? Dr. King, Lambert.

Lambert King Well, I think the thing that impresses the doctors who work at a place like County the most is how the patients feel about the hospital. In the 1960s a lot of federal money became available which would have permitted many patients who formerly came to Cook County to go to other private hospitals for care. And certainly some of them did, but larger and larger numbers of patients have been coming to Cook County Hospital particularly for our outpatient services. And when you ask them why they come, they say, "Well, my parents came here. I was, perhaps, born in this hospital, and that I consider to be my hospital." And I think, to a much greater extent than in a private setting, patients consider it to be their own hospital and they say they come there because they believe the doctors are the best.

Studs Terkel It's come a long way, hasn't it? Again, I'm--go back to childhood memories and myths and thoughts and people, Black and poor white, saying, "I'd never go there because they slip the black bottle to you. The black bottle." They want to kill you. That was also part of the myths because you went to a free hospital.

Lambert King Yes.

Studs Terkel And what you're saying now is, changes have been tremendous and some feel more at home there, you see, sure of better care than if they would be at a, I guess a free section of a private hospital.

Lambert King I think they feel much closer to the staff there, because the staff by and large comes from their own community, and they know that many people in their community do come there and they feel that the doctors are better than they would be and have more of a commitment to the patients than they would in other settings.

Studs Terkel So Chicago has one: Cook County. One: that's County.

Quentin Young Yes. Only one. We shouldn't neglect the fact there's a sister institution, a very big and very important one which is more of a rehabilitation and extended care place, called Oak Forest on the far South Side with some 1800 beds. And it's a very important adjunct to our work. The fact that Cook County Hospital has about half the number of beds it had when I was there, and literally in those days you couldn't get between the beds, they were so close together, and there was no bed census. Whenever a new patient came, you rolled out another bed, and soon you were in the aisles and in the halls. When I tell this to the young doctors, they say an old man's ravings, but I assure you it was true. Well, we have a fixed complement and although there are limitations in this old plant that keep it from being anywhere near where it should be in terms of amenities, Oak Forest has been a big solution to the problem. In other words. When a person gets ready to go to a less intensive care place, we can promptly move them out--

Studs Terkel And I suppose Cermak Memorial, of which you are the director of medicine, Lambert, that's part of the County.

Lambert King Yeah, it's affiliated with County and, actually, that's the third public hospital in the city. County is the largest one and then Oak Forest and Cermak is a third one which people don't hear about very much because it's behind the walls at Cook County Jail, and it's an 80-bed hospital which serves the more than 50,000 people who enter the Cook County Department of Corrections each year. By and large, these are people who have been charged with a crime but who have been unable to post bond while they're awaiting trial. And every day, about 250 people enter the Cook County Department of Corrections, and Cermak is responsible for providing medical screening for them when they come in and providing treatment for them if they should become sick while they are in custody. And of course, the people that come into the jail have by and large had very little medical care in the past of a continuous nature. They've only had sporadic care and there are many neglected problems which Cermak, I think, is trying to cope with and where we're making a lot of progress in terms of building a decent jail health system.

Studs Terkel Has here, too, a change occurred, say the prison hospital of the past and one of today?

Quentin Young Well, Bert King, you're looking at one of the foremost architects, young as he is, in improvement in health services in the jail. It's fair to say in the keen competition for the darkest chapter in American medicine, jail health care comes out on top. And Cermak Memorial Hospital, when it was awarded to the Cook County Hospital as a responsibility some three years ago, was a cesspool. It was an object of public disclosure and, indeed, they lost their accreditation. So we inherited a place that hit at absolute rock bottom and Bert King a year later asked for, and I was pleased to designate him chief honcho to try and put it together. At enormous personal effort and skill and leadership, he's brought it to one of the, really, one of the foremost places in the country, a model that has excited the interests of prison personnel all over. Now, we're not out, our goal is not to make prison a charming place. We have our own views about the barbarity that passes for penal activity in this country. Nevertheless, there's no denying those 50,000 young people, and they're all young Black people, give or take a few exceptions, are indeed the excluded part of the population that the public hospital is charged with. And while we're just in the foothills of a Mount Everest, Dr. King has the kinds of programs that will allow us to meet the health needs of people like that.

Studs Terkel So, what--we've touched upon, really, thus far, is that the public hospital, the general one, Cook County, the hospital in the suburb, the prison adjunct of it, has improved tremendously. It has. And you're talking not simply about Cook County but throughout the country.

Quentin Young Yes.

Studs Terkel Been improvement.

Quentin Young Well, there's two, there are really two currents going forward. On one hand, the phenomenon at County, I think, is mirrored in other major hospitals. But what I think is terribly important to understand is the last five to ten years, accelerated of late, has seen what I call an assault on the public hospital. Bert King was getting at it when he mentioned that new funding arrangements for the care of the poor took them off the dole and with either a Medicare or Medicaid card they became a very attractive item from the financial viewpoint. In other hospitals that have had their doors shut simply because they couldn't afford to take care of them or maybe other reasons, but whatever, given these tight money days for the hospitals, there was a new interest in the so-called charity or poverty patient. And that interest has taken the form of a steady assault on the public hospital. Let me document that. We're seeing now many of these institutions I enumerated earlier on being compromised or literally destroyed. Philadelphia General. This is a hospital, Studs, that was created before our revolution and a fantastic history of achievement, of patient care, of research, teaching, on the basis of one afternoon council meeting under Mayor Rizzo, whom you may have heard of, they closed that hospital, saying they canceled the new hospital--

Studs Terkel In fact, there's a recall movement underway for the mayor as a result of this particular--

Quentin Young Exactly, and I think that that has to be tied up. They canceled the match of interns, and they had a good group of people coming in, and of course that was a way of, like, cutting off the blood supply to the heart or to the brain. And they said, "One year, this important institution will be closed, and, well, guess what? All these patients will be taken care of by the private sector." I'd like to spend a minute, not now, in discussing the Marie Antoinette quality of that kind of solution. But to me it's extremely interesting and heartening no matter how it comes out, that that barbaric act did rouse the people of Philadelphia to move to--I'm sure there are other things they have against Mayor Rizzo, but the idea that he would destroy a hospital.

Studs Terkel Could we discuss this aspect of it? Bob and Lambert? A matter of what Quentin just brought up, a matter of this new assault now, up to now, the progress made to social awareness and the better treatment of patients in public hospitals. Now it appears there is an assault from left field or right field, shall we say, that involves money here, that is it's not a question of kicking the patients into nowhere, it's getting dough because a new source of income has come into being because of Medicare and Medicaid.

Robert Maslansky Well, that's the theory, of course, that these patients will provide ongoing--because they have a third-party payment available to them through Medicare and Medicaid, that they're a source of revenue to the private sector. This in actuality doesn't happen, though I think our patients at Cook, were they deprived of our facilities, would offer, for the most part, sort of an inarticulate moan. They just wouldn't be in a position to object the way I think those of us that are fairly articulate about these things could. And this is regrettable, deeply regrettable, that they won't have anybody to serve them.

Studs Terkel You mean these patients might conceivably just die of neglect, and that's it.

Robert Maslansky That--beyond theory, that's a fact.

Quentin Young At this moment, the point to make, what the Lord giveth, the Lord can taketh away, granted that the fiscal support of care for the sick poor made them attractive, and no question that many of the private hospitals, which were thought of as elite, began to see and take care of some of these patients, and they indeed were the authors of the notion, "Well, let's get to get rid of the County Hospital. We'll absorb them." But so delicate is that reception that when the current state government turned down the flow of cash into these hospitals, they not only screened, as well they might, you have to get paid for what you do, but they absolutely cut back services. And today, as we sit here, many important hospitals have limited care for Medicaid patients to extreme emergencies. They've cut out what they call surgery that is elective, and they're not going to take anybody in who needs repair of something if it isn't an emergency. Well, these are the people we're seeing in our emergency room today. So there you have this irony of calling for the destruction of a public resource at the same time when more and more people are being put in our care, and this is a national phenomenon. My own view, and this is a theoretical one rather than a provable one, that the precondition for setting a national health insurance scheme on this country, and we all know that's very much on the back burners moving up to the front burners, is the destruction of the public sector. Now that sounds like an extreme statement, but the logic is something like this: we've been seeing more and more a corporate model of care being foisted on the American health system. Some of the things that were criticized or thought of as backward like the country doctor, the doctor over the drugstore, has increasingly been replaced by a much more cost-effective corporate model, some having excellent principles of group practice behind them, still others being--trading on the lessons of big industry: heavy emphasis on high technology, heavy emphasis on the tests rather than the laying on of the hands. And this, of course, has run medical costs up the wall and created a national crisis. My own view is that, very rapidly, the people who plan things and make decisions are trying to get a handle on health services, and the handle will be what, unfortunately it seems to me, has been the American solution to everything: instead of the mom and pop grocery store, we're going to have a supermarket. Instead of easy-going country lanes and a reasonable symbiosis between transportation and society, we're going to have super-highways, and the public hospital stands in the doorway because its motivations are quite different than the private hospitals. Our interests are in changing the social conditions that send people to our doors, treating the patient in the early stage or, better yet, prevent the conditions that make his illness take place. The private hospital which may be enormously skilled and I certainly know that from my own experience, still is dealing with the end product, the sickness. All of their interests are in the sickness.

Studs Terkel Now we come pretty much to what may be the core of what it's all about. Not simply a Chicago battle, a specific of which we'll not discuss, but a national challenge here, isn't it? The issue seems to be joined between--this is beyond! This has implications beyond the hospital itself, doesn't it, implications of which way we go, more and more impersonal techniques used, a tremendous profit is made, but impersonal techniques as against a person-to-person contact.

Robert Maslansky It has to do with what's going to happen to the character of American medicine, and as Quentin was talking, I was thinking about my own bailiwick, education, and how effective we can be in a public institution promulgating ideas such as Quentin just discussed, the notion that medicine--A cottage quality to medicine should be retained. The laying on of the hands as against the use of a battery of tests somehow should be communicated to the next generation of physicians as worthwhile, and I think our institution is in a position to do it, perhaps better than some that have more corporate concerns.

Studs Terkel Let's--Lambert, before we pick up on this theme which apparently is the heart of what we're talking about, the nature of how is our society going and the metaphor, it's a hell of a metaphor, it's health, life, and death, might be the fate of the public hospital as against what could be described as corporate medicine. So we'll resume our conversation with Dr. Quentin Young, who's chairman of private medicine at Cook County, Dr. Lambert King, who is the medical director of Cermak Memorial dealing with prison care, care of prisoners at Cook County, and Dr. Robert Maslansky, who is director of medical education at Cook County, so we'll resume in a moment after this message. Resuming the conversation. Lambert King. Your thoughts that were brought up, you know, ideas by Quentin and by Bob on the matter of this conflict between--

Lambert King Rob was speaking about the training of doctors in a public setting and it seems to me that that's part of what the battle is about. In other words, are we going to train physicians toward an orientation of private fee for service practice, or are we going to train physicians to work in a salaried setting and in an institution where the commitment is to the public health, to a system which provides preventive care on a long-term basis. We've found at Cook County that since the hospital has improved and our training programs have become more and more oriented toward the care of the community, that we've been attracting far more graduates of good medical schools than we had, perhaps, five or six years ago. And during this period we found that the opposition of some of the medical schools which are affiliated with private institutions has grown and the criticism of the persistence of the public hospital has grown from the private sector and from certain sectors within the academic community who think students should be more oriented toward private practice. And I think that this is what part of the struggle is about in regard to the public hospital. An example of how we might train people differently at a place like Cook County is in the prescribing of medications. Several years ago we noticed that large amounts of tranquilizers were being prescribed in the general medicine clinic, and almost every patient walking out of the clinic was being put on tranquilizers because they had acute, agonizing problems of life. And rather than talk with the patients, the physicians in so many settings just write a prescription and get the patient out of the office without dealing with that patient in any more personal way. And as part of our training program, we strongly discourage this and we tried to point out to the doctors in training that this is not the way to practice good medicine and to get to know your patient well. And we've seen since that program was implemented we've seen a massive fall in the amount of tranquilizers which are prescribed, and we think there's a lot more patient-doctor contact going on as a result of this.

Studs Terkel By the way, this--didn't Quentin, you instituted this, didn't you, here at Cook County, a public hospital, but you put the ban on tranquilizers.

Quentin Young Bert said it all. We were in the bandwagon in a country where the number one drug that's being sold is Valium, the number two is Librium, etc.

Studs Terkel Private hospitals, too.

Quentin Young Everywhere. Everywhere. The number of prescriptions in this country in '74, we haven't got '75 figures yet, were two hundred--pardon me, two point five billion, over 10 prescriptions for every man, woman, and child in this country.

Studs Terkel Of the tranquilizers.

Quentin Young Of all sorts, with the tranqs right at the top. Now, you know, there's only one way to look at that, and only one conclusion to draw, and that was to break the habit of the doctors. Amazing thing of that particular effort was, not only did it work, but the patients didn't complain. The doctors were more distressed than the patients, because it put new demands on them. I'm happy to report it like a beneficent irradiation, it went over to the other departments--

Studs Terkel And also the doctor and the patient had more of a personal--

Quentin Young Well, that was the whole point. Talk to them, don't give them a pill. Now, lately we did the same thing with some very potent antibiotics. Useful drugs with very limited application that were being ordered indiscriminately; high-cost, many dangers, they're toxic to the patient, they also create organisms that are resistant when we're trying to preserve the potency of these drugs. And similarly, working in a public hospital where interest is to conserve and to prevent, we were able to put this through. I'm sure the drug companies don't like it. I remind you that about two years ago we banned the drug salesmen from the hospital. We had about 40 full-time drug salesmen assigned to nothing but "educate" our doctors. That's what we thought we were--

Studs Terkel You know, there are two things in my mind: one a very wild thought, I'll save it for later, that's the big one, that the public hospital, indeed, which once upon a time offered not the best treatment of the poor, may be, if preserved, if you can win, can be also a beacon light toward private hospitals in that they also would be treated more personally, could be more corporate, too. Let's talk about that now. The idea that here's this turn of events of history, thanks, I suppose, to certain doctors, certain kinds of doctors such as yourselves and your colleagues in different parts of the country, that the hospital that was considered bad has become almost part of the vanguard for the good, the hospital of the future and that the opposite of corporate medicine, of personal care, so that the public hospital may help the private hospital, because no private patients paying tremendous sums are also treated in that corporate cool manner.

Robert Maslansky There is a certain irony to that, that the alms house is now really the provider of the most humane care.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Robert Maslansky I think one of the things in education that we're interested in and largely why I'm at Cook County is to promote the notion that medicine is a one-to-one relationship with one individual. One physician, one treater. And the setting I've discovered in the last year that I've been there is one that I can do my best work in, and that work having to do with instructing the next generation of physicians.

Studs Terkel No doubt Bob Maslansky could have gotten a job at one of the bigger private hospitals, couldn't he?

Quentin Young Bob is too modest to point out he came from a very successful private practice in Minneapolis and just said he couldn't hack it, this isn't the way he wants to spend his life. I think that's true of all of us, the personal gains were there, but the alternatives are much more exciting. Studs, I want to introduce another dimension that's just important as curbing the drugs and teaching humane medicine. I know this is a favorite of my colleagues here, and that's getting out of the hospital. There's a paradox for you. The road to good health care is getting out of the hospital into the community. And this is something we've only got our feet wet at County. This isn't the forum to recount why we feel we haven't been able to do as much as we want, but I can assure you we're ready. People have come to the place both at the attending level and at the training level committed to get out into the community, to treat the patient "vertical," so to speak, rather than horizontal. Most of the patients in our acute care areas are testimonies to the failure of the system and the cost of keeping them going, as you know, in those places--our intensive care unit has to run about a thousand dollars a day. And we know what a thousand dollars will buy in prevention, or at least early care of hypertension, which is the most important cause of why people are stroked out in our units. About a thousand dollars will take care of about 20 patients for a whole year. Twenty human years. Based on the same cost for keeping a patient in those vegetable states for one day in a high-technology unit. I trust that equation isn't lost on a wary and concerned public, a public concerned with costs. Well, to get into the communities in a really exciting perspective and at the outset there would be places in this county which is our legislative charge that are completely abandoned. There's a place like Robbins, Illinois. Very interesting community in the south suburbs. It's one of the few all-Black communities in the nation. We went out there and talked with the mayor and some concerned citizens, many of them nurses and so on, who see the basic lifestyle problems afflicting their community. For example, there's an enormous number of widows. Why? Because the men are dying young of hypertension. Now, if we know anything about hypertension, we know we can control it and extend life and they were demanding that of us. They have the facility, they have the community will, it would just be a very exciting experiment. We have the people to go. Need some enablement, to be sure, but we see these opportunities multiplied throughout. We wouldn't have to compete with North Michigan Avenue doctors, or the--

Studs Terkel As you're speaking of this, I think of something Lambert said a moment ago, you and Bob speak of the tremendous possibility, the horizons that are so bright provided, the public probably is aware of it deep down, but trying to break through this corporate assault, we haven't mentioned medical schools. And you said the medical schools are tending to teach us to lay off public hospitals, tending to encourage the corporate approach.

Lambert King Many medical schools discourage their graduating seniors in medical school from coming to places like Cook County, and the discouragement is usually done in a subtle way, that they don't consider the public hospital to be as academically advanced as private teaching hospitals and as certain university hospitals are. Many medical school students don't listen to this, as evidenced by the number of students we've been attracting who come out. The approach is really very different in terms of the training program in a public hospital versus many private institutions where the emphasis is so much on super specialization. Our emphasis tends to be on the training of primary care physicians or general internists in our Department of Internal Medicine who are not so specialized that they can't practice in a community setting. Another thing that I might mention about our program that's different is the jail health service itself. I doubt if there's any hospital in the country, certainly any private hospital, in which the residents spend actual part of their training in a jail health service. During our three-year basic training program, our residents and interns spend three months rotating through the jail health service and our goal here is not only to provide better jail health care, which we do because these are good doctors that are coming through, but also to expose those doctors to the problems of jail health care which has been totally neglected by the medical profession in the past. In a sense it's a form of public service as part of the training program and you may have heard congressmen talk about "Perhaps we should legislate so that doctors who receive federal loans would have to spend a certain amount of time practicing in a public area or in a rural area, an area of need." While the Congress is talking about doing this, at a public hospital like Cook County we actually have implemented this kind of a program where there is a real service to people in need and where there is this kind of outreach that Quentin talked about. We're detecting hypertension in the jail, we're finding new cases of tuberculosis which no one has found before.

Studs Terkel I imagine just as Quentin was describing the discovery in Robbins, Illinois, I imagine these very specific revelations amount and add up. What you're doing is quite specific.

Quentin Young Absolutely. I mean, this is not some romanticized notion of getting back to community, something which has captured the imagination of the young doctors in training, and medical students. But is obviously a specific felt need in a variety of communities that have just been bereft of doctors. See, one of the phenomena of the last decade or two has been this drift toward specialization that Bert King just identified. So you have more and more doctors doing very highly specialized stuff, and that the concentration of doctors in the affluent parts of our society which means the fancy suburbs and the downtown offices--

Studs Terkel Before I ask Bob a question, this involves medical schools, obviously, I'll ask it now. How come? You speak of the growing awareness and the more involvement of the young doctors and the changes taking place for the better in public hospitals. How come--medical schools and medical education is your world--how come these medical schools have taken the opposite approach?

Robert Maslansky Well, I suppose I'd be cynical enough to say there's an economic reason. I think young physicians--and also sort of a behavioristic reason as well, young physicians tend to emulate their mentors. Most people in medical schools are secondary and tertiary-care providers, highly specialized, that is, the teachers, and I presume the model that they establish for their younger colleagues is just that, that the action, so to speak, in medicine is to be the super specialist, the joys, and but that's not the case, obviously. It's only that this is the model that's developed in the last 50 or 60 years in medicine, in American medicine. I think it has and it might very appropriately have been developed because there were certain historical influences at work some 40 or 50 or 60 years ago that made it appropriate then for people to think anew about what the character of American medicine was and to so-call, to scientize it, as it were. But I think the trend in that particular trend has probably outlived its useful utility now, and it's now up to us in the public sector to re-humanize medicine, to devolve it from the concept of tertiary care as being the place where a young physician gets his gratification. That would be my long answer to your short question.

Studs Terkel I'm thinking another dimension appears here. Public hospital and the role, how so much it's a part of the American battle today. That is, the specialist and the all-around person. You know, the age of specialization again has had its impact here too, is it not?

Quentin Young Very much. So much so that it isn't just the zealots sitting before you who've made the observation at the very best all we can do is call it to the attention to the powers that be and set a few examples in our own settings. No, it's not national policy to do something to curb the counter-productivity of over-specialization in particular in the surgical specialties, but in general in all of medicine, so that now, for example, neurosurgery has all but cut down any new programs and is sharply curtailing the others because they overtrained the number of neurosurgeons they needed. A number of highly specialized surgical callings have had that kind of critical soul-searching. Almost all of the legislation having to do with health manpower have one or another approach toward curbing the training of specialists and toward stimulating and rewarding the training of primary care physicians, be they family practitioners, primary internists, or pediatricians.

Robert Maslansky I think it should be pointed out, though, that at a place like County, which is a very large institution and which obviously has many specialized functions, that we also are attracting superb specialists in all of the areas. They're part of our system, they're part of the way that we provide very good healthcare, and it seems that the specialists we're attracting are specialists who desire to work with primary care physicians and who desire to work in a system which emphasizes health care all the way from the early preventative end to the highly specialized patient who is very sick, and examples of this, of course, are seen in our trauma unit at County, which is a model for the nation.

Quentin Young You know, I think Bert emphasized something very important, that there is a continuity of care at County that we can provide and the atmosphere there is such that the most refined and sophisticated deliverer of specialized service does relate very readily and easily with the man on the line, as it were, and the sophisticated--I should use that word in a more guarded way--the tertiary care deliverer--

Studs Terkel You say tertiary care.

Quentin Young That's the man all the way down the line. That's the court of last appeals, as it were. He comes to County because he knows that's an ambience where he can relate to his colleagues that are on the line and is willing to do it and wants to do it.

Studs Terkel The word that, my favorite word and the one Bob just used and is the key to this is continuity, isn't it, continuity as against alienation.

Quentin Young Let me draw on that because I want to give you a perfect example of how values are placed in the training period and what we did to change it. The classical training of an internist is a year internship, where he's at the bottom of the ladder. He's--by internist I mean specialist in internal medicine, okay? He's an intern, which means everybody tells him what to do. And the next year he takes, he's in charge of the wards, in other words, the general medical patient. And the third year he goes to the specialties, and that's the end of his training. Now doesn't that tell that young man something? There's a bottom of the ladder, there's a middle of the ladder, and then there's the top. Well, we looked at that and said, "That's wrong." That guarantees that his next step will be to take further training in hematology and gastroenterology simply because all the value systems said that's more excellent, that's a greater achievement.

Quentin Young So we changed it. They have that same first year of internship when they're learning all the rudiments of the craft, the next year they go on the specialties to learn one thing: what the specialties to paraphrase Kennedy "can do for them." When--the third year at the top of their powers as a trainee, after two hard years at County you're a pretty hep cat, they get put on the wards and they are the chief of the service there with that specialty experience behind them as an aid so they can know what the endocrinologist can tell them in a tough problem. Now that made a big difference in the value systems of our people.

Studs Terkel There again the implications are tremendous, aren't they? Keep coming back to the public hospital and the country at large and values. It's a shifting of priorities, to use a much overused word. It is, isn't it, so instead of a specialist being the end, it's in the middle as he comes, again you have continuity as Bob said, you have an overall connection, one to the other, as the third.

Quentin Young Well, this has been the strategy at County, Studs. I think you'd be misleading your audience if you led to believe that this wave is universal. I would say at this point we are the minority, we are the ones who are crying in the wilderness. We'd like to think that at least some of the ideas we put in are the answer to the national problem. But this assault on the public hospital in Cook County is no exception. It can do all the suffocating that's necessary to end this tendency.

Studs Terkel So there is this assault. And as this roundtable, a very impromptu one, comes close to the end, we really see no reasons for this assault. It's part of the whole general pattern, is it not? That is, the corporate impersonal, mechanized non-human approach as against something very personal.

Quentin Young One has to believe that the drug companies that deal with County Hospital are not exactly enthusiastic about our banning of the drug salesmen or their cutting of the sale of their high-cost drugs by many hundreds of thousands.

Studs Terkel Well, you're talking about established, to use an old-fashioned word, established vested interests are involved here too, aren't they?

Quentin Young Those old foes and--

Studs Terkel Can I ask one further--here's the thing. Hasn't, with the development of public hospitals becoming more and more socially advanced and as far as the patient much more salubrious, too, hasn't there been also a growing patient awareness in the country of rights and wrongs? Lambert?

Quentin Young Well, I'll tackle it. There's no question that the patient is much more sophisticated. I lay a good deal of this to the media. The linear media in particular deserves a boost for this. The patients are reading and do care. The question of patient rights is closely linked to the civil rights movement and the expressions there. I think the day is over when you can make any plans that don't include community input and that's a very exciting thing, because I think at County we're just beginning to create constituencies that, more than anything else, will be our defense where needed and our support where needed for the financial and social and political requirements for us to go forward. I think that's a very wholesome thing because it links very closely to another idea strongly held among us, namely that there is no solution to healthcare that doesn't anticipate increasing self-reliance. I can't just be, "Go home and suffer." It has to be sharing of skills. My model is the blood pressure cuff itself. As a practicing physician, no matter how carefully I took it, I would observe a patient's blood pressure for about two minutes every month if I saw him that frequently. Giving that patient a blood pressure cuff and teaching him or her how to use it adds a wide-open dimension to my ability to take care of that patient. First of all, visits can become much less frequent; after a certain point, stabilization of a drug regime if there's one in place can be done over the phone on the basis of transmitted information, the patient can learn by taking his own blood pressure what indeed raises it. When he has a headache, is that due to migraine or is it due to his blood pressure rising? Is that a warning signal or something irrelevant to his blood pressure? I use that example because we have, just as a thermometer emancipates a head of household or a mother with children and she can tell whether her kid has a fever, which is the beginning of wisdom, so, indeed, a blood pressure cuff can be a liberating effect for millions of people with that disease, and one could go on. That's a very simple--

Studs Terkel This, of course, is precisely the opposite of feeding the tranquilizer approach.

Quentin Young Exactly, and it's also the opposite of having them come back to the office a lot, or being more interested in the end stage of that hypertension, which is a stroke or a heart failure or kidney failure, which is an extremely high-cost disease as opposed to an even lower cost because the patient's doing a good bit of the care.

Studs Terkel We come back again, do we not, to the human being, don't we? That is, the part--I suppose you'd call this participatory medicine, in a way, wouldn't you?

Quentin Young Of course! And we've robbed people of their right to care for themselves. We've told them, "You can't die at home because nobody could possibly take care of a dying person," whereas the reality is, any person or group who's raised a baby can take care of a dying person with any kind of additional help from visiting nurses or what have you. This robbing of people of their autonomy, of their self-reliance, of their self-confidence is one of the hallmarks of corporate, technocratic, professionalized structure, and we'll have to reverse that or we all perish.

Studs Terkel This is what it's about, really, we're talking about public hospitals. Suppose we have a go-round here. We have a little time left, to go round. We began talking about the public hospital, the history of it, the development, the change from an alms house and rather cursory treatment of poor patients to advances, Cook County being a notable example as well as some of its sister hospitals elsewhere. And then we come to the assault on it, corporate medicine, [result? resolve?] for many reasons, and we come to now. Some thoughts, perhaps, that come to your minds as doctors directly involved. Lambert King.

Lambert King I think it's a battle which is touch-and-go at the moment, and I don't know, you know, what the future of the public hospital will be. I think that its fate depends upon the extent to which the people that it serves can act effectively in order to become involved in the decisions which have to do with its funding, which have to do with its personnel, and with how the money is spent, and whether or not there will be adequate money in order to fund this kind of medical care, and it does come down to a political question about whether or not the people who care about a public hospital will have the power that's necessary in order to save it.

Studs Terkel Bob Maslansky.

Robert Maslansky I see the public hospital as the repository of what is good in teaching medicine. And my concern being largely for the next and successive generations of physicians, I would for one regret the passing of that institution. And I think it's a very critical battle we're in right now, a critical time of that battle. We have to muster all the support we possibly can get. And have the public understand that what the public, what the institution, the public institution, does provide is a very meaningful part of our country.

Studs Terkel Quentin Young and also, perhaps Quent, as sort of addendum, what people can do about them.

Quentin Young Okay. To me, I hope after this hour it's clear in my mind at least that it is a not so microcosm of the total crisis in this country, the right of people to control of their own lives. The posture that this society's going to take toward ever-increasing corporate control. The whole question of alienation, powerlessness, it's all embedded there. And while at this point the struggle seems unequal, I think that it's very well to point the bicentennial year that maybe our particular Boston Commons may be the public hospital, and the competence of a society that is indeed concerned with health care to see in it at least the hazy vision of the future, the removal of profiteering in medical care. The confronting of the vested interests who, however skilled, however excellent in what they do in particular, distort the healthcare transaction. A political question of participation. Again, the special interests that manipulate services for political advantage, and, indeed, the whole question of how we train a profession. Humanistically, patient-oriented, responsive, motivated at least by modified venality, if not altruism. These are the several issues that I think are the agenda no matter where you look. I'd add another dimension. For a whole bunch of reasons, the health question has been greatly enlarged. To me, very few public social issues that aren't health questions, whether you're talking about ambient pollution, the radiation hazard, drug pushing and its assault on the morale of our young people and our not-so-young people, water conservation, you can go on and on, housing, and without I trust being the ultimate leveler, suggest that these are all health questions, and each one of these, no matter how you look at them and I know you've looked at a bunch of them, the solution has to lie in a enormous involvement of the society as individuals and as groups. So that points, I guess, to the direction of your tail of your last question, what's to be done. I see no pathway, no shortcuts, any more than those guys on the Boston Commons did. People have to become aware, they're going to have to identify where their interests lie, and having made that judgment be prepared to struggle for them in all the arenas we have: the electoral, the media, the interpersonal communication, they're going to have to defend what's good and, of course, fight against what's bad, including what's bad at County Hospital.

Studs Terkel Thank you. So the question is the public hospital. More than that, it's a question of public health. More than that, is the question our values and where we go. Quentin Young, who's Chairman of the Department of Medicine, Cook County, one of my guests, his colleague, Dr. Robert Maslansky, who is the Director of Medical Education at Cook County Hospital, and Dr. Lambert King, who's Medical Director of the Cermak Memorial Hospital connected with the Cook County Jail. Gentlemen. Thank you very much.