Tavern owner Eva Barnes discusses her life experiences

BROADCAST: 1968 | DURATION: 00:53:14

Synopsis

Content Warning: This conversation has the presence of outdated, biased, offensive language. Rather than remove this content, we present it in the context of twentieth-century social history to acknowledge and learn from its impact and to inspire awareness and discussion. In the 2nd of 4 parts of "Division Street: America," Eva Barnes talks about her background. Barnes recalls when she was little, her family was poor and they had to move from place to place. While working at a meat factory, Barnes said she tried to organize a women's union because although the men and women were doing identical work, the men were being paid 59 cents an hour and the women were only being paid 28 cents an hour.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Eva Barnes I don't go in their homes visiting them, but I know them and we meet at the mailbox, say hello. We meet in the store, say hello. Yeah it seems like more people are more afraid of talking to anything to progress it. You know, if you talk anything about improvements of your neighborhood or anything, right away you're afraid of being called a communist. That this is the word they're afraid of. I remember when--in 1951 when my husband was paralyzed and our septic system got clogged up in the tavern over there. This is--if it wasn't true, it would be funny,

Studs Terkel What system got plugged up?

Eva Barnes The septic tank system [voices in background], we haven't had no sewerage at that time here. So my 9-year-old son and I, we got out there and we opened the four corners up. My husband's paralyzed, he couldn't help us, I couldn't get nobody for any money to open the tiles up so because the water was backing up in the tavern. And I was working out there, you know how that sewer tar is out from the sewers, it's just like tar and it clings to your skin. My poor son up to his elbows--up to his armpits. He was all covered with that black tar and myself, and I had the tavern closed up that day because I couldn't go draw a glass of beer with these dirty hands out of the septic tank, run and wait on people. So then my neighbors come walking down the street. They said, "Look at her. She's working like a communist." I thought to myself, she was--why do they have to say I'm working like a communist today? I'm trying to keep this going myself. I can't get nobody to work. Why do they find me like that? I hear even now you get to pick up a newspaper, in today's paper. If it seems like when somebody is doing something good for this, like these here civil rights workers, right away they're communists. Blame them. Why do they always give the communists the credit for that? [laughing] This is what I can't understand.

Studs Terkel I want to come now to Eva, the beginnings. Look, where are you from? Where were you born?

Eva Barnes I was born in Riverton, Illinois just a few miles out of Springfield, Illinois. I was one years old when my parents took me to Ledford, Illinois, southern--further south. My father was a coal miner and when the coal mines decided that they had enough coal piled up, my father was out of work. Before the First World War, I remember the script. We used to have to buy our groceries in a company store with script, not money, there's little coupons. I remember there's 25 cents, 15, 10 cents and a penny, nickel and a penny. And we had to depend on company store for food, clothes, coal from the company, and it seemed like my father was in debt. It just--just as soon as he starts working to pay off his debt and company gets closed down and we're out of work again. So again, my dad packed up the family, moved to another company that had a coal mine. So we moved like gypsies from one town to another. I could go crazy mentioning all them. Watson, Eldorado and Harrisburg, [unintelligible], Herrin, Buckner, Sesser, Weaver, Benton, Logan, all of these towns. One after another, little towns. Then when we got--when I got to be 11 years old, we moved to Zeigler, Illinois. I stayed in Zeigler till I was--a couple months before I was 12 years old. That was 1923--24, and I left and came to Chicago because there was no way of making a living. There was no future in that town. If you call working housework five dollars a week and taking care of four children for a girl 11, 12 years old.

Studs Terkel Your father was a coal miner, your mother--how many children in your

Eva Barnes There was five of us, nine altogether. But there's four left, five died in infancy. There was a high rate of death rate at that time in the mines for children. I remember my mother used to have--every second year she had a baby. And I remember her--how bad times were that she'd take the old stale curtains and wash them out and use them for gauze to make nipples for the children, for the babies to suck crackers and sugar out of them, from an old cheesecloth. They couldn't even buy gauze.

Studs Terkel How old were you when you started working?

Eva Barnes I think I was about 9 years old when I started doing housework, housework and taking care of children. And then when I left Zeigler--when I was 12 years old and I lived in Zeigler, I swore I'd never do housework no more, take care of somebody else's children except my own if I ever have any. When I come--then I come to Chicago.

Studs Terkel Did you do mining work yourself?

Studs Terkel No, but you did housework. How old were you--

Eva Barnes Housework, and in those days the boarders used to--the miners used to board by families as much as four and five. Some places had seven boarders and there was a lot of dishes to wash, extra 50 cents you wanted to earn so you go over by some lady and say, well you come over in the evening and wash the buckets, miner's buckets or dishes, so you get an extra 50 cents a week for

Studs Terkel Did you have a chance to get much schooling?

Eva Barnes No, I went to 7th grade. When other children were having vacations, my mother hired me out to work for five dollars a week. That was my vacation when I went to school. Two months before I was 12, I came to Chicago and it was in winter time. I had 65 cents in my pocket. So I got a job at Omaha Packing Company 23rd, piece work. And I don't think I'd ever got the job because I--but I was an overgrown girl. I looked big for my age. So this is--

Studs Terkel What were you now, about 13, 14?

Eva Barnes Just 12, a little over 12 when I got in the line. I think there was about 250 people, Negro and white, standing on the platform waiting to be picked off for a job. In those days they come out. There was no union in those days. And--

Studs Terkel This is about 1924, around then.

Eva Barnes 1924. So then this employment manager comes out and he says, "Hey, you big one over there!" He points his finger at me. "You big one!" I turn around, he said, "Don't turn around. You, come here." I said, "Me?" He says, "Yes, you. How old are you, about 19?" I says "Mhmm". [laughing] I was afraid to open my mouth. I said "Mhmm". I was only 12 years old. So he hired me as a 19-year-old.

Studs Terkel No, no, this is wonderful, this is great, you just--

Eva Barnes He says, "You know how to sharpen a knife." Well, back in the coal mines, we used to butcher our own hogs and our own beef and I said, "Sure, I know how to sharpen a knife." So he hands over a steel and a knife for me and I start sharpening. He says, "Okay, you'll go to work." So I worked at Omaha Packing Company for quite a while, piece work. I was making good money and now I was making my first paycheck. I made so good, I don't exactly remember how much it was, but it was an unusually big check and I got scared. I thought the company made a mistake, so I quit the job. [laughing] I quit the job and my mother got worried because I sent her, I think was five dollars I sent her in a letter, and right away she thought the worst thing happened to me, you know, in Chicago.

Studs Terkel She thought you were walking the streets.

Eva Barnes Yes, because it's too much money for a 12-year-old to live here and then send five dollars home. So she sent one of the men that was coming to Chicago to look me up and see what kind of a life I was leading. [laughing] He comes over and he finds me eating ice cream with my landlady and her children. "What is she doing? She sent her mother five dollars, a mother's word." And Mrs.--the lady's dead and she was my landlady. She said, "She is working!" And at that time I had the real--my finger was cut real bad. I had cut the index finger real bad. "She's working", and it's all cut up, but I worked--

Studs Terkel What kind of work was it you did at the stockyards? How would you describe that work?

Eva Barnes Pork trimmer, trimming meat for sausage. But I practically done everything in the stockyards. So I even--

Studs Terkel You went back later to work at the stockyards.

Studs Terkel I didn't mean to interrupt your story. Tell us, this is a good story, you're telling it.

Eva Barnes Well anyway, I worked in the stockyards till we started organizing CIO. We were working--took us off of piece work, they then put us on bonus which we didn't like because bonus you had to work harder than you worked piece work and we had no union, nobody to represent us. So the men were organized, but we women weren't. So then there was a fellow named Bill Collins. He'd come up and ask me, he says, "How would you like to organize your women? How

Studs Terkel How old were you then?

Eva Barnes By then, I was about 21 or 22 years old.

Studs Terkel What other work did you do? By the time of the first marriage and before that. Pork trimming? Stockyards?

Eva Barnes Ooh! I was in stockyards up--everything, pork trimmer, I worked in the laundry store. I think to put me to work at every job in the stockyard. I even worked in the [off haul?]. I don't know if you know what off haul is, it was where all the guts and everything come out, come in there. During--this is Depression time now. This was--

Eva Barnes Now it's the 30s. This is when I--they bumped a Negro girl to save me a job because I had two sons and I didn't like the idea. But then there was a fellow named Dick White. He was cutting the pigs' heads and he says, "Don't worry about it. We are used to it already."

Eva Barnes Yes and this--working on these guts, they were cut and then opened and I had to sterilize them, wash them and the ones that were condemned, you couldn't touch them because if you did, you would get a hog itch. And you had to keep your hands--a cold shower on them all the time to get that hog itch off of you. So he jumped down. I couldn't keep up because I was sick to my stomach [laughing] and my children used to, when I'd come home, "Mommy," he says, "we love you, but you smell awful." But this is all from the off haul, which you get used to. You working there so long you can't smell nothing no more. But this--I'll never forget this colored boy, man, not boy, man, Dick White. I'll never forget his name. I don't know what happened to him, but he saved my job and he says, "Just--you'll get used to it. Just don't think that that's what you see it. Make pretend it's some flowers or something so you'll get over it." [laughing] And I got used to it, you know. But this is working with the Negro fellows, you know. And then we start organizing the women in there because the men were organized. And this is what they were telling, get the woman organized. So then I made connections with CI--no, AF of L first. It was AF of L.

Studs Terkel This was the 30s now.

Eva Barnes And we've got AF of L in this. Bill Collins, he says, "Miss, don't organize so fast." I had 40 women the first day I went out. "Don't organize so fast." I says, "They all want union. They want to get better wages. We're doing the same kind of work men are doing, trimming meat, sharpening our own knives. Why don't we get paid same like the men?" They were only paying us, I think, 28 cents an hour. And the men were getting 55, 59 cents an hour for identical work. So when I told him, I says, "Well we get--when we get union there, we're going to get same wages." And we signed with the AF of L, but pretty soon there was between AF of L and CIO there was trouble, and they were--one couldn't get power and the other one want to come in fighting between each other. And then I decided--I went to a couple of the CIO meetings and I found out they was better, going to be better for us if we go with CIO. So then we switch to CIO. That's Depression times, like I said. And then Roosevelt come in, and then again the Roosevelt come in. And I was carrying the biggest Roosevelt button on, biggest button and I go to the job and I didn't know that that was the opposition company, it was for opposition. So I got laid off, you could say Warwick Radio. I had a big Roosevelt button, they told me to take it off. I says, "No, I'm for Roosevelt." "So you're for Roosevelt, you get out. You don't get a job."

Studs Terkel This is for a radio company?

Eva Barnes Yes, Warwick Radio. So then--

Studs Terkel What were you doing? What kind of work were you doing

Eva Barnes Assembling radios.

Studs Terkel You've done everything!

Eva Barnes See, so then the--he says--when he says he can't use me no more, and this is Election Day, the day Roosevelt--Election Day, I just got through voting for Roosevelt, now I lose my job. I had a job all through the Depression and now the first day Roosevelt gets elected, I lose a job. So in this--this is when I met Felix [Sabut?]. This--my husband, the late husband that died and the both of us looking for a job. He got a job himself in--as a beef lugger. I don't know if you know what that means.

Eva Barnes The beef lugger is a man that carries half a steer or quarter hind or front quarter or hindquarter of steer from these hooks that are in the freezers and puts them in the truck. They call them luggers. It's a heavy work and my husband was a pretty strong guy. But it took him, later on to come up on him. And then it was again funny all the time. We--after we got married, we looking for a job. He's too old and I'm too fat. We couldn't get a job. I was young enough, but too fat, too heavy. So, what are we going to do? So we went in tavern business. Those days, I don't know. Today I don't think--I don't know anybody that would do that I see. I had cooperation of people. If I was a bad person, I don't think they would have helped me. And here this big manager of a brewery company helps me out. Of course, I had to pay a dollar in every barrel of beer that I sold. I had to pay extra dollar to help pay off what I owed him. And then the whiskey houses, they brought in all the whiskey and wine and liquors and everything, and the lady across the street, the tavern lady, she closed her own tavern up. She knew we were new, we didn't know how to mix drinks. We didn't know how to make a hamburger, we didn't know nothing. She closes her tavern up, takes her bartender, gets all the glasses, we run out of glasses. She comes across the street, put her bartender in it behind the bar. Frank from 24th and Halsted, he brings his two bartenders on, Steve is still on Archer Avenue. He's got a cabin there today, Steve, that's his son. Frank, Steve and Rudy. The three of them behind the bar and Stella's bartender, four of them behind the bar that told us to get out, mingle with your guests. They took over the bar.

Studs Terkel Something you just said. Now these people all cooperate to help you. You said "in those days". You think it's a little different today?

Eva Barnes I don't think--I never heard of anybody today going out and helping anybody like that. I've seen it in--over here, right here, say I lived all these years and when my husband was paralyzed all those years and sick, he never turned down the fire department, the donation. He never turned down any police benefit donations. He never turned down neighbors if anybody passed away for a flower piece, you know, a sympathy note or something to the neighbors. And yet when he passed away, nobody came to my door and said that we're sorry to see Felix go or something, nobody.

Studs Terkel What do you think

Eva Barnes I think, what I think, the deeper--the more I think about it, it's this fear of the war in Vietnam, fear of the communism, fear of atomic bombs. It's--there's a fear there. And I remember, you know, when Roosevelt--I don't know if you was maybe too young. When Roosevelt said, "The only thing you got to be afraid of is fear itself." Nothing else but fear you have to be afraid of. If that you conquered, then you were all set. But I always say this way, I'm not afraid of nobody and nothing. Only thing I am afraid is in case there should be an atomic war. If it hits me or anywhere close, I hope it hits me and just sizzles, you know, and that's all, to be nothing of me. Just like, strike a match. These things is I think what people they read, they don't know what they're reading. I myself, I get confused. The president tells you that he don't want no war, he has peace. You pick up a paper, they're bombing the children on television. The guy is being interviewed talking about peace and the picture is being shown where the woman and children are being bombed and slaughtered and murdered. How--if I think that way, I have a bad feeling, how are other people that have their mentalities not strong enough to separate the cause of it?

Studs Terkel Bewilderment, confusion, panic.

Eva Barnes And fear. What's going to happen to us? What's going to happen to our kids, our grandchildren?

Studs Terkel Before we come to your views and impressions, this is all part of it. So you open the tavern. How long would you and your husband have that tavern?

Eva Barnes Well, till my husband died in 1959 and it was--I say I could thank Roosevelt for it. If it wasn't for Roosevelt being elected and opening--repealing the 18th Amendment. I guess it's called 18th Amendment. Well I'd still be bootlegging! [laughing] I wouldn't, no, I wouldn't. I can't understand. When I was 16 years old, I knew how to make moonshine and home brew and today out, if you tell me how to make pickled beets, I couldn't do it!

Studs Terkel You did about--Eva, you must have done about every kind of work there is in the world!

Eva Barnes I've done everything. I even--I worked in the rubber factory. Oh Christ!

Studs Terkel What did you do in the rubber--what kind of job? Always hard work.

Eva Barnes Always. In those days, they used insulation rubber around the automobile, around the windows, the rubber insulation. I was a trimmer on that and I made steering wheels on the great big band saw. I don't know how I didn't get my arms cut off. Made steering wheels, and worked in the candy factory. Now look, this I'm telling you, I had all--I was not a bad looking girl. I mean, I had opportunity.

Studs Terkel You're not a bad looking woman now!

Eva Barnes Thank you. When I hear people say all the children are bad delinquents from broken homes and girls turn bad because they have nobody, no mothers, no fathers, you know, to confide in, talk to. I had all the opportunities in the world to become bad. All of it. In fact, one case where a girl--I'll never forget, her name was Anna [Kloss?]. During the Depression, there was an old couple that needed a stove and she didn't--wouldn't give them the requisition to get the stove to heat their place up. On 35th and Ashland Avenue used to be the old Wrigley Building and they had the relief station there. So I went there and I put that Kloss against the wall, I got her by the throat, when she made the--she suggested that I was--I come in for this stove and she says, "Well, you're not a bad looking woman. Why don't you get yourself a job and buy a stove?" She thought it's for me. I says, "Not for me, for an old couple. I'm helping all I can," I say, "I can't help them no more." And then when she made that suggestion that I'm not a bad looking woman she said, "Why don't you get married?" I says, "What do you want me to do? Get a mattress on my back and walk up and down 35th Street?" "Just get married." All the opportunities in the world to become bad, I didn't. I worked.

Studs Terkel You took her--you had her against the wall and you made her give a stove to the

Eva Barnes She give, she turned the requisition over. Not only stove, but she got a requisition for the fair store, and they went down got all underwear and blankets and everything. But this is a long time ago, I think--I don't see why people should have to struggle for everything that is important to them. If they tell me--in the Constitution they tell us that this, under our Constitution you're--I found out by being arrested. When you're arrested, you have no Constitution.

Studs Terkel Why were you arrested?

Eva Barnes For the end of war in Vietnam with the students.

Studs Terkel I want to hear about this. I was just about to ask you about what do you think of demonstrations?

Eva Barnes I think it's good, it's good exercise for me. [laughing] The only way I can get my exercise is in these demonstration marches and for good cause, I don't mind that. I won't--I have never demonstrated for not a good--for anything that is--

Studs Terkel Suppose we go back. What led you to feel the way you do? Now, I know how you feel about Negroes. You were raised that they were human beings and you lived in the area. So now we come to the matter, other matters, like you're protesting the war in Vietnam. You march for peace. What led you to this? How did you come to believe this way?

Eva Barnes Well, I first belonged to the Women for Peace. That was--when we started was the "Ban the Bomb" in Washington. That was my first big

Studs Terkel What made you join it, is what I mean. What thoughts? I mean, what

Eva Barnes Well, I tell you, my first husband, and though he was no good, I don't know whether it was the First World War or what had to do with it, but he was wounded in the First World War real bad that he was pensioned. He's in an old soldier's home and he's all crippled up and whether that war had to do or not, but he used to tell me, "I fought in the First World War," he says. "I fought in some kind--" He was decorated in some kind of a medal he got over there to end all wars. So to be--his sons won't have to fight in a war. That's what he was--fought for. Well, along comes Hitler, of course starts another war, another war is started. So then my oldest son was not quite old enough, but just before the end he was old enough already. So he had to go. Well, he got out of there and then my second son did--the Korean War started. He was old enough to get into Korean War. Thank God that my first one come home safe. He was a little bit what they call brainy, intelligent, so he was in decoding, then pencil work. He didn't have to handle a gun. So he'd come home safe. And the second one, he was in the Korean. I don't know how long he was in Korea. He was a married boy and, you know, newlywed and he corresponded mostly with his wife. I was a mother, but left on the outside. More closer--his wife was more closer to him because three days after they were married, he was shipped to Korea. But he was there that--he had a thick bushy hair head. When he come back, I think it was a spot, two and a half years. He come back, he's bald-headed. His hair come out and he's a different boy altogether. I know that this Korean business had to do.

Studs Terkel In what way is he different?

Eva Barnes Well, he isn't--how can I tell--he isn't--maybe because he's a man now, he isn't jolly no more. He's very strict with his own children. He's just like a bully in the training, the army training, the meanness is in him, left in him. He is not-- meanness was not taken out of him when he put down into civil society. But maybe I'm wrong, I don't

Studs Terkel You mean, the joy was taken out.

Eva Barnes Yeah he is. He never was a bully. Now he's a bully. And I guess they've trained him like that. Now, this boy I got, this last one. He's a good boy. He's never given me trouble. He's never missed a day of school. He's never been late to school. He's never harmed anything. I'll tell you what kind of--if there's a mosquito is in here, he won't kill a mosquito, he'll say, "I'll let him go." [laughing]

Studs Terkel Like Gandhi, you ever hear of Gandhi?

Eva Barnes Yeah, he says "let it go". And he gets along with everybody and the kids, little kids, they're just--they're crazy for him.

Studs Terkel He's the policeman now

Eva Barnes Yeah. And he always wanted to be a policeman. And he's a boy--I never let him buy, have a toy gun. I never--I says I don't want my children to have guns, I will not buy a gun, I will not allow in my house a gun. And my children, none of them had guns, toy guns. I would never allow them to go and shoot, you know, like playing Cops and Robbers or Indians and that, nothing [unintelligible]. There's other games you can play besides shooting at each other even not in pretending. And this is the way I believed in. Why? I don't know. Why? I don't know. I never did fight. I'm not a fighter. I don't fight. I never fight, not even with--I left my husbands, but I never fight with them. I'm afraid. I'm too big, I weigh 300 pounds. My husband weighs 135 pounds. If I hit him, I could kill him. [laughing] No judge will be sorry for me. If there's somebody, a nice looking leg, you know, kind of look to see. But mine, I put these here big hams up there, wouldn't even look at it.

Studs Terkel So this is what led to your feeling and so you have a third son, a young son, 22, and now it's Vietnam comes

Eva Barnes I don't want him to go in Vietnam. So we're here now, alright, he's got a dangerous job. He's a policeman. That's a dangerous job. But I feel different about it. He's got a gun on him. He's got--he's doing everything what I'm against. But as long as he knows, and I know I says I don't believe in police brutality. In no way. No way, it's unnecessary because once a criminal is caught, oh sometimes you've got to defend yourself. Yes, but you don't have to provoke it. Because when I was picked up after that demonstration, there was a lot of them police were trying to provoke even the matrons. They'll come to me and practically says to me, "Now Mrs., why are you demonstrating with these commies?" Students. I hear the priest, nuns marching along and she's calling them commies. I don't see that. She has got the upper hand, the matron. She takes my purse away, takes my glasses away. Then she says, "You can make one phone call." I said, "Alright." And then they lock me up in the cell. Everything's taken away from me. I said, "Can I have a paper cup so I can get a glass of water?" Now this is 4:00 we're picked up. "No." I wait till 10:00. So then I cup my hands to get some water and to rinse my mouth. But then she takes you again. And they just move you from one cell to another cell and then they fingerprint you and they take your picture and all the time they're talking, they say, "You ought to be ashamed of yourself. Why don't you stay home and mind your own business? Why don't you do your--take care of your family instead of going on mingling with all these bunch of hoodlums and bums?" I didn't--see, this is the only time I ever come in a bunch with it. The intellectuals, the educated students, university students. Here I'm in this neighborhood, sitting here I can become a dummy and here I learned something, you know, I learned geographical locations. The games are played, we can't see each other, but they had an education class going on which I like, and I said, "You got the upper hand. Alright, I'm not gonna argue with you." "Shut up." I said, "Oh I'm not saying nothing, I just say you've got an upper hand." "Shut up." That's all what they know. "Shut up." I probably could buy and sell her if I wanted to. You know, she's working for--I pay her tax--her wages. I pay big tax, I pay 1200 dollars a year taxes. How much taxes she's paying? But I can't talk to her. I am not--I have no right to say nothing to her. I don't--I never believed that a person when he's arrested--I've seen people get arrested in southern part of Illinois. My father was arrested for bootlegging and I've never seen him treat--be treated like that. And here I'm marching peacefully and he tells me, he says, "Do you want to--are you gonna move or you don't move?" I says, "I'm going to move."

Eva Barnes Yeah. So I moved. But he comes back again and says "I told you to move", so I moved again. I said, "I'm moving!" "Do you want--" he says, "are you going to walk to the patrol wagon peacefully or do we carry you?" And I took a look at him and I said, "Look," I said, "I don't want your officers get ruptured." I said, "I might as well walk." [laughing]

Studs Terkel Was that the first time you were arrested, when you marched in these demonstrations?

Eva Barnes First time in my life and I've done some things that I should have been arrested for. [laughing] I should, like I said I was 16 years old, I cooked moonshine and I could smell it, the chief worked--lived right across the street never pinched me. I made home brew and they never pinched me, and I ran--run parties all hours of the night. Nobody had me arrested.

Studs Terkel But they arrested you for marching for peace.

Eva Barnes For peace they arrest me, says my God, I wonder if I would murder somebody, would they arrest me then? They don't arrest nobody in Mississippi. They got different law for them over there.

Studs Terkel Tell me, what were your thoughts, your impressions when you were in jail? You said these people with you, they were--they play these games about geography? These people arrested with you, your thoughts about them.

Eva Barnes Yeah, they were a happy bunch. They're educated. Well, for example, we had a psychiatrist and we had a retired society woman, at one time she was Mrs. Evans. She must have been a society woman at one time because she's an educated woman and lived most of her life in Florida. And she's a property owner, got a home in Florida. She's not a poor woman. And another fella that was again, some kind of a businessman, I don't know. And there was priests and all these college students.

Studs Terkel So you learned something while you were in jail?

Eva Barnes Yes. I learned. They played the geographical game that I haven't played since we were--when we were kids. You know, spelling classes, it was just like a spelling class, just was not a spelling class. And all these different freedom songs. But the beauty of it is that they take your glasses away, they don't want you to wear glasses, then they come around to bring Bibles for you to read and you can't read that. You can see your hand in front of you. How you gonna read the Bible?

Studs Terkel Are you religious?

Eva Barnes Well, I think I am. I think I am religious. I live the Ten Commandments and I don't--maybe I don't believe in the same kind of god like other people believe, but they say when they go to church or go to confession, their sins forgiven no matter what they do. My God don't forgive me if I do something wrong.

Studs Terkel You don't go to church anymore?

Eva Barnes No.

Studs Terkel Why did you give up church?

Eva Barnes Well I give up the church when--this is a long time ago and I was first married, my husband worked in the coal mines and he asked me to give him meat for Friday. And I was a very religious girl. I wasn't going to give him no meat on Friday, so I had some kind of a soup on the stove. I had that soup, my powder, everything thrown all over the floor by my first husband. And when I went to the priest and told the priest when my husband did and he said, "Next time he does that to you, take a skillet and hit him right in the head with it." No matter, even though I didn't like what my husband did, but I loved him in a way then. And I kind of resented priest telling me to hit my husband in the head with a skillet. [laughing] I didn't go for that very much. I said what the heck kind of a priest is he? I saw--right there, see, I didn't believe in fighting already. I says no. So I better don't go to church. I just quit going off again

Studs Terkel When you were in jail, you made--you had one phone call to make. They let you make one phone call,

Eva Barnes Yeah, but they wouldn't let me make it. They thought I could make it tough, you know, about 2 or 3:00 in the morning they called my son up and they said--first she come up and ask me if I want to have that phone call made. I says, "Yes. Make it." "Well who do you want us to call?" I said, "Call my son." She says, "You want us to tell him that he should come and bail you out?" I said, "No." I says, "I don't want him to come bail me out." I says, "Tell him to take the beans off the stove because they're going to get spoiled." It was hot dog day! Oh, this was really cute though. In the cell--this is about 1:00 in the morning. I hear a real banging on that steel wall, you know and I'm a heavy woman and the--my--in this tacked onto the steel wall of the other cell. And every time I moved, you know, that wall would move and she plopped, she hit the steel wall. She was like, "Hey you! Quit moving in your bed! Every time you move, you knock me out of my bed." There had better bounce up, you know. Say this side and now the other side is attached like that, and I'd move and then like a spring, you know, and then throw her off. So she says, "What are you arrested for?" I say, "I'm arrested for peace, fighting for peace with the students." She says, "Well, I am arrested too." I says, "When was you arrested?" She says, "This morning. It wasn't right," she says, "I shouldn't be in here." I said, "Well, what was you doing?" She says, "I was soliciting." I said, "Without a license?" She said, "Why do you need licenses?" I says, "Where are you from?" I says, "You in Chicago, you got to have a license for everything." She says, "I'm from [unintelligible] in Long Island." I said, "When you come to Chicago, you owe $5.23, no less, in the county building" I said, "And you go to the county commissioner's office and ask him for a solicitor's license, then nobody's going to arrest you." And the matron comes over, she says, "Will you shut up?" [laughing]

Studs Terkel So when you said you were arrested for peace, she thought you meant the same thing she's talking

Studs Terkel She was street walking.

Eva Barnes She was a street walker, and I was thinking when she said soliciting. Well years ago when--this was another thing, I worked for Leiter Credit House on 18th and [unintelligible] in there somewhere, and they gave me a suitcase and a paper. I had--they called me a solicitor and I had a permit to go from house to house with this suitcase selling clothes for the Leiter Credit House. And I said that "I know when years ago they called me a solicitor, they said I had to have a permit. So you must have a permit too." [laughing in background] And she says, "You're kidding." I said, "No." I said, "I'm not kidding." I said, "It's true."

Studs Terkel You're talking through the wall.

Eva Barnes Yes. And then later on she says, "You was kidding me." I said, "Yes I was kidding you." I said, "I know what you mean." But I said, "You know, you girls are foolish." I says, "Anyway. I had a tavern on 61st and State Street." And I said, "I used to see the girls be picked up, and they picked them up, the police themselves. These are not colored policemen, these are white policemen. I've seen them. They pick up the girls and if the girl, she is a known streetwalker, I guess they call them prostitutes, professionals, and she is known and they come in and they tell my husband, "Get that streetwalker out of here!" They'd call her worse names than "streetwalker", you know, then you can't use the name over here, you got a lady in the house. [laughter in background] And my husband said, "How do you know?" There be four of them maybe sitting there. "How do you know that she's so-and-so?" And this policeman say, "Well, we know because she just got out of jail this morning." And my husband say, "If you know she's such a woman, why don't you put a mark on her so people could tell? I don't want to get my face slapped going tell her now. Are you, ask this woman, are you so-and-so? This is--she's not doing no harm. She come in here, spend her money just as good as anybody else's." And then we've--I've seen where the policeman picks up these girls and the girls throw--flip their wallets over the bar and let our bartender and my husband hold their wallets for them because the policemen, they take their wallets from them, take them a couple of blocks around, and drop them off in the alley some place. Now next time you better have more money! See.

Studs Terkel The girls knew this and they trusted you and your husband. But the fact is, the policemen would do this. They would roll them.

Eva Barnes That's right. To take the money from them, encourage it, go ahead, do some more. In fact, if you don't have more money, they're going to give you--maybe with the billy club, beating or something.

Eva Barnes Yes, the vice squad. Now this I lived with, I seen it. And if it went on then, it's still going on now.

Studs Terkel Yet your son is a policeman, is a different kind of

Eva Barnes I hope so. If--he's my son and he's a policeman. If I ever hear or see that he does--that he's brutal in any way, I don't care how--to defend himself, I mean like if somebody's going to come out with a weapon at him, he's got to defend himself. But deliberately to encourage--even the other day I say, "If I ever find out you take a bribe or deliberately set a trap for somebody just because take advantage of your policeman's job, I'll be the first one to"--never got a whipping, but I would beat the shit out of him. I would.

Studs Terkel You remember--certain things stand up in your mind, certain memories you have are very vivid that you never--events in your life like your ma--when you got married, your first marriage, the wedding. My

Eva Barnes My first wedding, my first marriage I'll never forget as long as I live. I was 16, of course we won't go into the ages of the men, but the wedding was more than a week long. We had, in those days, the neighbors all pitched in. They made doughnuts. We went to the farm and bought the whole calf and the whole pig. I think it was 150 chickens, and home brewing and homemade wine, everything is homemade. And got married in church with all the--everything, bridesmaids and High Mass and everything, the whole works. And in fact, even the coal company superintendent, the owner, the super--not Bill [unintelligible], but anyway from Springfield, some coal company. And he brought silverware for a wedding present for us. And because I danced with him, he gave me 35 dollars if I would sell him my wedding shoes. I sold him my wedding shoes, everything was sold, I was sitting in only my slip, even the dress was sold from me just to raise money for the newlyweds in those days. This is 1925. And of course, there's a lot of pictures taken. We were pictures in "The State Register", Springfield paper then.

Studs Terkel So you would come to Chicago to work and you went back home for the

Eva Barnes Yeah, I went back, married a coal miner. Zeigler,

Studs Terkel Zeigler, Illinois.

Eva Barnes No, no. Bulpitt, Illinois. We got married St. Rita's Church in Kincaid, Illinois. That's just a few miles out of Springfield near where I was born, near Riverton, Illinois.

Studs Terkel He was a coal miner.

Eva Barnes He was a coal miner. And the wedding, like I say, the head cook, woman cook, everybody was drinking and everything was homemade, like I said. It was barrels of homebrew and wine and it was berry wine and peach wine, everything you could think of, and eats. There was plenty to eat that this woman that was the head chef cooking all the stuff, she was backing up into the closet. And there they had set up a tub of grease that they were cooking doughnuts in. Good thing that grease had cooled off, she sat right into the tub. [laughing] There was grease all over the floor and all over her. They couldn't cook doughnuts, they were through cooking doughnuts in those days. And for the wedding. But, like I say, the shivaree, I don't think they do this no more. But we had shivaree every night, every night. I think late, maybe 2, 3:00 in the morning, they would be banging cans and making all kinds of noise and you--the newlyweds, you couldn't sleep at all. You had to be up and my poor husband, that time he had bushel basket of candy and all kinds of small change and that's the only way that he could satisfy the mood. Kids, you know. All hours of the night, they weren't doing nothing bad. But I don't think they do the shivaree business today. Yeah, but that was something because in the next morning, you go around and you figure well, gee, you won't be able to face these people in a shame because they kept you up all night long and now the next day they're here again, they come knocking on your door, they see your--the wedding is still on. I think there was more fun in a wedding, like now they go with the cars around tooting the horn and everything. But I still think in 1925 it was nicer wedding days. People were used to--like I say, from my young days I knew how miners lived poor. And the only ones that really had money is the woman that had a lot of boarders and a woman that bootlegged. This is prohibition time. But the woman that didn't bootleg, that had boarders and didn't bootleg, she just from hand-to-mouth from--like the here in the city, from pay to pay.

Studs Terkel It was kind of a sharing feeling, wasn't

Eva Barnes It was. Because I remember what we to call picnics. We'd go out picnic, we'd go fishing at first. All families, the single fellows would pitch in, they'd say well, we'll buy all the pop or ice cream. The married men would buy the--make the homebrew. And the women would bake the cakes and the breads. And then the young boys, say the young lads, 17 years, they'll do the fishing, catch all the fishes. And the girls will go picking berries or something if it was berry season. Everything for the picnic. Then when you went to the picnic, there was no money exchanged, no commercial. Everybody like one big family. They cook a big pot of Mulligan stew and everybody share out of that. That was a picnic. Today you go to a picnic, what it is, it's commercial. Everything, you buy your ticket, you buy your popcorn, you buy your beer. If you haven't got a fistful of money, you ain't got no picnic. And if you bring your own bags, basket at a picnic that isn't for commercial, then they say, "Well you're no--you don't bring no profit for us." But anyway, my wedding, it was the biggest wedding in Sangamon County in 1925. They said that nobody had a wedding like St. Rita's would. The church was dressed up real beautiful. This is the days when I was a very religious woman. A girl rather, not a woman. And not long after that when the priest told me to hit my head--my husband with a skillet on the head because he asked for meat on Friday. I thought well, the [unintelligible], but I still loved him and I didn't think priest was right in telling me to hit him in the head with a skillet. [laughing] That wasn't right. I still loved him.

Studs Terkel I suppose the enjoyment of life, life is very important to you, isn't it? Living to the full, life.

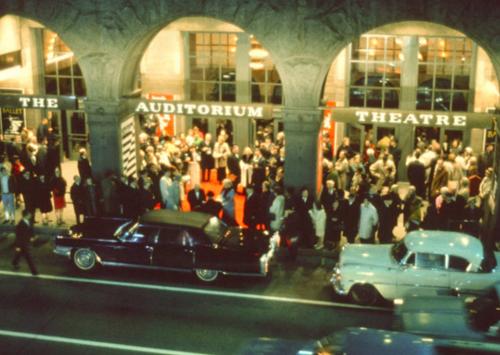

Eva Barnes I like to live. I like good times. I like to read a good book. I like to see good movies like "My Fair Lady", I enjoyed it very much. And in fact, I think that's the last movie I saw. It was in Florida in St. Petersburg. And I enjoy watching television. I like, well, what I should say, what is special--I like educational programs, something like history, Black history, historical stories I like. I don't like to see war pictures. I don't like to see one of these cowboys and Indians shooting and all that, a gun shooting. I don't care for that. I saw coal miners when they get killed come out of coal mines all crushed. I saw in the First World War, my mother had seven young boys come from Europe to stay with us. They worked a little while in the coal mines and they were drafted into the American army. They were not even citizens of this country. They were young boys. I think they were 20, 21 years old only and they never came back. My mother had seven stars in her window because the government didn't--they were registered from our house. And as my mother was like a mother to them, they couldn't tell that they come from Lithuania. At that time, Lithuania was known as Russia. Lithuania was not an independent country. It was under the Czar's rule at that time. And instead of putting that they were come from Lithuania, they said they come from Ledford, Illinois. So they send the star to my mother. And whatever little belongings that they--little memento chains or something, credentials that they had. And many times, working in the coal mines, they'd bring people out. I mean, every time the whistle blew in a coal mine, there was a fear of who's dead now, who got hurt now. Everybody run to the coal mines. Many times I run down the railroad track to the coal mines to see who was it. Was it my father? Was it my uncle? Was it--one of my girlfriends lost seven husbands killed in the coal mines. Seven! One after

Studs Terkel You mean, she was a widow seven

Eva Barnes Seven times in Zeigler Coal Mines, seven times and all young husbands she had. Every time she married one young man, two, three weeks later he got killed in the coal mines. Her father, seven husbands she lost in the coal mines and two brothers. And all that tragedy just enough--there death is enough. I don't like to see nobody get killed. I don't like to see nobody hurt. This world is beautiful