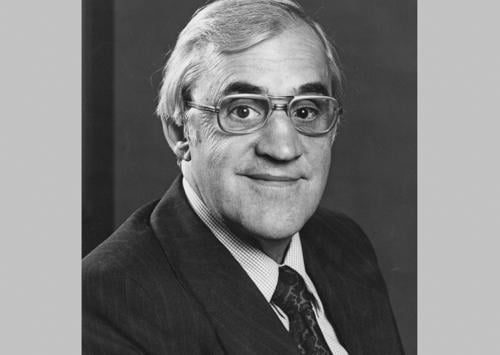

Leon Golub discusses current art projects at the Museum of Contemporary Art

BROADCAST: Sep. 6, 1974 | DURATION: 00:44:12

Synopsis

Leon Golub talks about his current art projects and the power of the largeness of a canvas and its representations can have in the art experience.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel [Exhibition?]. We're together, Leon Golub and I. It is now Chicago, September 1974. Tonight, Friday night, is the opening of a Leon Golub retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art on 237 East Ontario, [be there tonight?] through September 20th. And Leon, we were just listening to ourselves 12 years ago, 10 years ago, Paris, Chicago, and much has happened in those 10 years, to you as an artist and to the world.

Leon Golub That's certainly true. Uh, it -- we have here the paintings which date from those Parisian days, including paintings which are earlier than that, from my first period as an artist in Chicago, then Paris, then New York, and the current work that I'm doing at this moment in New York.

Studs Terkel Let's sort of wander arbitrarily. Okay, this is a, we have no Mussorgsky music at the moment, but it is pictures at an exhibition we wander through. Now, I'm looking at a -- you -- by the way, these paintings are sort of large in a sense, they, they, you believe in bigness, don't you?

Leon Golub I think what I'm trying to state through the figure I can state better large than I can state small. Usually, this is not necessarily always the case, but typically. I'm trying for a kind of mural style, therefore something larger than life size, something that can be seen close up, because there is a kind of intimate surface to them, but primarily, more important than that, can be seen from a distance, almost like it's on a wall somewhere. You approach it, you see it from a distance, you become aware of what it is, and then you are into the reality of the thing, and suddenly you realize the thing is larger than life size, that it has something to do with the scale of our own actions.

Studs Terkel So you're talking now about the largeness that is possible in man.

Leon Golub That's right, and in a sense, to exaggerate our own actions is to see them in a very special light. But a light that's realistic in terms of what is possible in movement, in struggle, in the appearance of the figures themselves as we face them.

Studs Terkel Even now as you're talking, Leon, my eye touches, sees this huge reclining figure. It's a man reclining, and to me the layman, sort of looks pretty bruised, but by God, he's strong, isn't he?

Leon Golub This painting is called "Reclining Youth". It's 13 feet, six inches long. I painted it in 1959. It is taken very specifically from "The Falling Gaul" in a Roman museum, therefore, it comes out of the Pergamon style, the late Greek style, and I'm trying to make some sort of recall to Greek style, the same time that I intend it to be much cruder. It's certainly much more eroded than the original is, which is excellent shape. I destroyed it in part. The thing is thrust up as a kind of in a sense a victim in terms of our own world, but there's a recall to the classic in it, and a recall in a sense to what that classic figure meant in its own time.

Studs Terkel As you're talking, it occurs to me, this is remarkable, the continuity. This this figure we're looking at now, we wander away for a moment cause it's huge, now I want to look at it from a distance with you, the artist. It was painted five years before you and I had our last conversation 10 years ago. So is the aspect of continuity always in your work?

Leon Golub Yes, there's a logical continuation and a certain uh, attitude in respect to aggressors and victims. For example, "The Dying Gaul", the original "Dying Gaul", the Greek's sculpture is a victim in the sense that he was -- the Greeks were the, rather the Gauls were the captives and the defeated of the Greeks. Now, there's a connotation of that in here. This is a defeated figure, the same time the figure is intended to be enormous, and therefore it's -- in its over-life-sized quality, it's intended to have a kind of thrust and vitality, like the fact of its origins in a defeated form.

Studs Terkel Even though defeated. I look at him now, this figure, defeated, but far from dead.

Leon Golub In a sense, despite his wounds, the figure has the capacity, the seeming capacity to stand up and move into action again.

Studs Terkel Now that's it -- to move into action again, again is an interesting word here, isn't it, again. Because earlier, remember, if we looked back to the beginning of this conversation that the audience is listening to this morning, 10 years ago in, at the Krumpkin Gallery and 12 years ago at your studio in Paris, you spoke of survival and overcoming.

Leon Golub Yes.

Studs Terkel You're talking about.

Leon Golub And in a sense that this figure like this have a great deal to do with that kind of attitude. In a sense, its survival quality, almost has to do with its fact that it's almost like a rock. It's constructed like a rock. Uh, rocks endure. There the relationship between skin and rock in such a such an object. Such a painting. Skin is fragile, but skin is, skin is tough. This is the skin we carry around us. It's tough, but it's fragile also. Rocks have tremendous endurance, in a certain sense, the wounded quality contrasts with, even conflicts with the capacity to in a sense, exist.

Studs Terkel As you say that, [going beyond?] the broken skin and the rock-like quality, we see muscles and blood, too.

Leon Golub Right.

Studs Terkel Muscles and blood.

Leon Golub Yes. Correct. Correct.

Studs Terkel There. Let's go here. You, you guide. You be my Virgil. Not that I'm

Leon Golub This is a painting from 1960 which is called "Fallen Warrior", which is a second take on a theme that I have used three times. "Burnt Figures". The -- I did the first group of burnt figures, burnt men, 1954 and '55. This is from the second group from 1960 to '61. The third group I did in 1968, '69 and '70. In this one, it's an incinerated figure.

Studs Terkel Why don't you describe it even perhaps even more specifically? It's an incinerated figure, you mentioned burnt.

Leon Golub Well, the figure is actually taken, like the one we just saw, the figure is taken from a Greek sculpture, It's taken from the great altar of Zeus in Pergamon, and it's as much as I can it's almost like an exact not so much copy, but replication of the position of the figure so that someone who is acquainted with the original figure can, uh, seeing this figure, recall that and therefore make a contact to the past. But the original figure, of course, is been eroded by time, but it wasn't intentionally eroded. This is intentionally eroded and burnt and scarred and is intended like the one we just spoke of, "The Fallen Youth", to represent these in a sense, almost continuous organic conflict between struggle, endurance, survival, pathos, fallen, et cetera. The figure, therefore, has to me, despite its open torn quality, have a considerable degree of strength, and I want that strength to be evident to it, but I want it also to have and not necessarily paradoxically, this quality of being incinerated.

Studs Terkel A couple of things come to my mind as you're describing this figure and talking. These are recurring themes in your art and [another one you are?] thought about the world that is not unrelated to your art. You spoke of burnt figures, incinerated figures. You did this when, what year'd you do this?

Studs Terkel Sixty. Uh, the word napalm was just about coming into being and used, too, not that I'm jumping the gun a bit perhaps, but nonetheless, the artist is very often prescient. The artist is often prophetic. In a sense you -- is not accidental that the year 1960, into the '60s and just about our first knowledge of what we're doing in Indochina was coming into our consciousness, too.

Leon Golub All right, now that might have been a little early for my awareness of this. I was aware of Indochina in terms of the French, you know, uh, effort for domination in Indochina, uh -- this it -- it originally had to do with the quality of being burnt. I didn't think of it in terms of Indochina. I didn't necessarily think of it in terms of concentration camp, which I thought of in terms of the earlier things. Uh, the more curious -- yes, yes, right. The most curious aspect of it I might have thought of it perhaps partially in terms of something like Hiroshima where it's burnt in a particular way. The most curious aspect of it to me, which doesn't mean that I was aware of it at the time, is that it resembles certain photographs I've seen from Indochina of burnt figures. In a sense, what it might say is

Studs Terkel Which

Leon Golub Which was in the air.

Studs Terkel By the way, which

Studs Terkel After you made this

Leon Golub Let's say in '65 or so. So and when I do napalm paintings in 1969, I am specifically conscious of Indochina, in this I'm not conscious of Indochina perhaps not at all. But I'm conscious of the notion of the incinerated figure as it exists in our own mind, as it exists in our own time! It's part of our time.

Leon Golub Part of the brutalization that we see all around us.

Studs Terkel The other thing comes to my mind as you're, you were describing this figure, the other phrase you used, strength, throughout. In the midst of all this, you speak of human survival. And here again, this is also a recurring theme in your work, isn't it?

Leon Golub Yes, I think the figure has strength, and it's intended to have strength. It's eroded, it is intended to have strength. I try to work with the polarities and I try to put it together in this kind of form. It's generalized. It has relationships to classic art, classic art being to my mind, the most perfect example of the fully functioning capacity of the human body in action in the world. That's how the Greeks and the Romans in part determined the possibilities of movement, possibilities of action, therefore I'm highly conscious of that. At the same time, I wish to take this figure and put it in a social milieu where all of these thwarting aspects have taken place.

Studs Terkel Classic art, here you're going to come to something -- the other, the other matter concerning Leon Golub, the most distinguished artist to come out of Chicago and now internationally known, is the fact that you have never -- the aspect of flow. Flow was always part of your life. Classic art, the lessons of that is something you have never forgotten. You don't abandon that, you just take the best of it, or as -- as best you can and bring it up to your work now.

Leon Golub I would like to be able to take, in a sense, the lessons of classic art, the possibility of movement, the possibility of man measuring himself through his own capacity of making gestures which have effective social meaning in terms of a situation, of using proportion, proportion being the proportion of body, having something to do with proportionate actions or effective actions. I am interested in that. But at the same time, I don't wanna have a Pollyanna attitude toward these things because we live in a world of a tremendous stress and strain. And this affects how we look at things, and this affects our capacity for action, and it certainly affects my capacity to view what are the possibilities of action.

Studs Terkel Yeah, now, Leon Golub. You're talk about possibilities of action. Far from Pollyanna, your work indicates a great deal of agony, and adversity and suffering. But at the same time, you speak of possibilities over and beyond what has been. Isn't this -- I'm curious. I'm not up on the world of art these days. Aren't you unfashionable? In a time of the impotence of man, the impotence, the powerlessness of people seem to seems to be the mode of the day?

Leon Golub Well, in one sense, I'm unfashionable. And if one looks at certain movements of art that are taking place which are extremely current, then there would be very little interest in the nature of the attitude that I bring to art. At the same time, I think that this exhibition alone is a indication that there certainly are pockets or places of interest and therefore, in a sense, my work is seen and its attitude is recognized. But it's not fashionable in the sense of the fashionable marketplace, or of this world that we often recognize as a kind of special art world.

Studs Terkel So Campbell soup cans don't interest you too much.

Leon Golub Well, I don't want to, uh, lay into, you know, Warhol or anyone else, you know?

Studs Terkel I'm really thinking about the world as we were walking

Leon Golub -- It's not a subject of mine.

Leon Golub It's certainly not a

Studs Terkel subject As we're walking to the museum from WFMT, we heard the earlier conversations just to revive, you know, just to rekindle our thoughts, you know, our thoughts, we were talking about how overwhelmed we are by banality today and by the trivial that made it -- we may just smother as a result of it. Your approach is something entirely different. Possibilities. Man becoming. The word becoming might be it. Man not just what he is, but what the possibilities are. There's a past involved, suffering, some learning perhaps. But it wouldn't beyond that. At least that's the way I Yes.

Leon Golub -- Yes. Yes, and I like I like the notion of exertion and stress. And I like the notion of going against things, and pushing, you know, and in a sense, shove and counter-shove and the struggle that has to be in order to make anything even take place. So you have to shove very hard. That doesn't mean you have to shove against the people in an aggressive manner, it's you have to shove and in, sometimes in art, you have to shove within the internal components of your own art so that you're not banal, you're not stereotyped in your own work. That you force through something which has a kind of endurance quality of its own. That is to say that an art object has to survive, an art object has to, in a way set up by itself from the surroundings around it. It has to have some sort of look, appearance or strength of its own, or else it is going to be overwhelmed by all of the chance things that are around us. And I particularly am one of those artists who does not move into the environment and in a sense does not take everything around as part of the facet of his or her work. I isolate certain things. I want a certain distance. I want a certain separation, and I want to exaggerate that separation to dramatize certain actions. What takes place in these paintings are their protagonists, who are engaged in a dramatic action. It's almost like the notion of the classical drama to the unity of time and place and concentration. A very strongly concentrated action takes place.

Studs Terkel As you're talking, we just wandered into another room of the museum, and you spoke of time and place and action and protagonists. And there's a huge panel here, mural in feeling, this one in which somebody seems to be slugging someone else who's on the ground, and a third figure seems to be helping the figure who is down, helping or pleading this

Studs Terkel Aggressor. Or watching. Though seemingly

Leon Golub Yes. I mean, it's again ambiguous as we, as we saw at -- when we went through the earlier tape, the second or third figure, its role is always -- not always, but often ambiguous, because he might be seeking to help the fallen figure, or he might actually be supporting the victor in this kind of struggle.

Studs Terkel Let's take a look at these three guys, and you tell me. What I, what I see is -- now, looking at it in more, more -- what? Intently than a moment ago, I see this huge, seemingly victorious guy, taking a whack, perhaps a rock or a fist, to destroy the guy down below who's on his knees. That third figure, of course, the most cryptic of all, perhaps, that third figure, he seems to be pleading where the apparent victor or apparent strong -- pleading, at the same reaching out with his hands to help the fallen one. And yet maybe an impotent person too, I don't know.

Leon Golub It's possible. It's possible. It's ambiguous. I should say about the painting that this is called "Gigantomachy IV", it's 10 feet high and 18 feet long, just to get some scale to the figure. Therefore, the figures, which run from the top of the canvas virtually to the bottom, are at least nine feet tall. This gives some notion of the scale of the figures. The word "Gigantomachy" comes from the Greek word meaning "Battle of Gods and Giants" and -- or "Giants and Men", as the case might be. Anyway, it's a giant battle, and in a sense, these figures are giants or they're men or they're heroes, or they're in a sense almost like robots at one level, because they're like fighting robots in a man's guise because all they do is struggle. They're ambiguous in all of these relationship, but they aren't supposed to indicate, is as much as is a great deal of stress, a great deal of violence, but done in almost as direct and simple a manner as I can possibly make it, and yet I want in it a curious dignity. But I don't want them just to be monsters. They once talked about the Chicago's -- certain Chicago artists, myself included, as a monster school. Well, these are not just monsters in that sense, though they take on man's guise and they take on man's gesturings in space.

Studs Terkel Several things you said as I'm -- as we're still watching these three figures, huge and Godlike and a sense of dignity is, you say, it's quite apparent there, too. At the same time, we live in a world of so much technology and machines, you said they're almost robot-like. Almost machine-like in their -- what, their tradition of machismo. That's [both?] of these guys.

Leon Golub That's right, that, that is a machine-like quality. It's almost inexorable that they carry out this kind of gesturing.

Studs Terkel At the same time we see human beings here, that's the -- the other aspect, thing you mentioned, we continue as we walk through, lead [kindly like?], is the ambiguity throughout. The ambiguity is there all the time, isn't there? The question, is he or isn't he? Helping him or hurting him.

Leon Golub It's like every position can be seen from an alternate position, the minute a position is stated, the minute an artist makes a claim, a philosopher, a politician, anyone. The minute they make that statement, almost the opposite sets up confronting you. It's like matter and anti-matter, the opposite is possible. That doesn't mean one doesn't have to make decisions or shouldn't make decisions, but the point is that there is always a set of ambiguities which are operating, and it's simplistic to take a thing on, always straight on. One has to face the ambiguity that the artist is presenting or that the situation provides.

Studs Terkel As we wander into a third room now, you and I have talked to one another, looking at one another, at the same time suddenly I find I'm staring into two, two huge faces. Two huge faces. Are they alive or dead? Those eyes. Scarred, of course. Strong. What do you see? What did you have in mind

Leon Golub This is called "Colossal Heads", it's a painting that's around seven feet high, 11 feet long, dating from 1958. The huge heads have probably, are probably influenced by a huge Roman portrait heads, for example the well-known head of Constantine. At the same time these heads have a certain quality, a stone-like quality and a quality of staring into space. They have a kind of absolutist aspect to them. They're not portrait heads in any sense of the word. They are generic or generalized notions of the human head again seen under tremendous stress but stabilized and caught in this moment, they're like monuments in a certain sense, but they're monuments which are highly eroded. They're like, almost like, Easter Island heads, things left from another culture virtually which one encounters, and one sees the stress on them, when doesn't necessarily know the sources of the stress, although one can attribute stress to them. They exist in this level of frozen stress or kind of vulnerability.

Studs Terkel Vulnerability. That's the other phrase I haven't heard you use yet, vulnerability, always that too, which also is humanity, too.

Leon Golub Yes, yes, and these are extremely vulnerable in that, in that sense. In fact, the technique is even a vulnerable technique in a sense that I -- it's not just an image of presenting it, but the material is made vulnerable by the way I destroy it in the process of working on it, so that the material becomes as vulnerable as the image.

Studs Terkel Can you, can you describe that further?

Studs Terkel -- The vulnerability of your approach of material.

Leon Golub On this particular case, this was done with lacquers. I now paint in acrylics, but I do the same thing. Basically. I build up many coats of paint, and the thing has maybe 10, 12 coats of paint on a surface. Then you had the finished look and it had rather a clean look, where the paint is clean. Where even the acrylics have a clean, flat look about them, almost like spread satin of the things we put on our walls of our homes. I then lay the canvas on the floor, [because?] that clean look doesn't appeal to me. I lay it on the floor, and it's absolutely necessary for me then to destroy that look, and I destroy it by putting many layers of lacquer solvent on, on the canvas. The lacquer solvent or thinner erodes the surface, digs into the surface. I then take tools and scrape away paint to varying levels, and, uh, then I rebuild next few weeks. I will rebuild the surface and I'll scrape it away again. Eventually I get a surface which has been built up and torn down, and this torn look which is a continually structuring and restructuring, and again tearing down, is how the painting is finally arrived at. It's a process in time in a certain sense, because it takes a long time in a sense to build them up and tear them down. But it's a kind of analogy to what happens to things in time. For example, I talked about rocks before, rocks erode in time, nature rebuilds maybe then through one means or another. But erosion is continuous, rebuilding is continuous.

Studs Terkel As a tearing down, there's a building, there's an erosion, there is a -- rocks are not resurrected, humans are, we trust. But this is what it's about, too, isn't it? The fact that it never ends, never ends. Something new. It takes on new form, doesn't it, all the time, but it's there. The basic, the basic figure is there.

Leon Golub And there is on my part a destructive impulse in it. That is to say, I don't like to see things whole. I like to see them torn down. This will show, particularly in the late paintings, where I cut holes in them. You know, where I really, where I really start taking them apart as painting, but this painting is a rectangle, which is 11 by seven feet. I haven't destroyed the rectangle. Later on, I destroy the rectangle, which is part of the same destructive thing taken further. Partly that's because what I desire to is a kind of natural thing. In other words, I like the fact that how time works. Time works naturally on objects. I like the notion that the painting itself is subject to time. I try to sometimes hurry this along, and so if I -- sometimes old objects come down to us and they're broken or torn. This has always been very attractive to me. I like the notion of a fragment. A fragment means that the thing is not ended. It's a piece of something, but it's a piece of a larger whole. When I make a fragment, or I think of a painting as a fragment, then I don't think of it as a total whole, a totally complete thing. I think of it as part of an ongoing process perhaps, part of some greater continuity. But all we have of it is maybe this fragmentary aspect, but the fragmentary aspect presupposes completion.

Studs Terkel It's funny, as you speak of, we wander now to some earlier paintings, I just can't help but be caught by something you said. You spoke of fragments, the fragmentary nature, too, of life today, not unrelated to atomic fission. The fact is, the smallest element in nature at the time the atom was split and fragmented, and that had to have an effect on every aspect of our lives, art and politics as well.

Leon Golub I think, that, in a sense, everything we deal with becomes open to fragmentation today in ways that maybe weren't even expected 20, 30, 50 years ago. You know?

Studs Terkel As you're talking, we now hit this other wall and these earlier, these are Chicago works before you traveled, right? We're coming to now.

Leon Golub Right. Right. Something like this is 1955. It's "The Damaged Man". Its very title explains it in one sense. It's like a skin. It's like a hung skin in -- I don't, I wasn't thinking of this when I did this, but for example, there is in the Sistine Ceiling uh, a painting of Saint Bartholomew, in which he's holding his own -- in the Last Judgment, in which he's holding his own skin. This notion of the skin as representation of the man, not so much body and bone and muscle, but the skin itself. This is almost like a skin with bone projections from it. Therefore, in a way, it it's a kind of extremely isolated and in a way tormented kind of figure, and in that sense, much less unified, much less put together than some of the later work. I don't mean unified as art, but I mean in terms of a concept of, of, let's say, the logical use of the parts of the human body,

Studs Terkel This was 1955 and you said it was not quite integrated, it was there. You yourself then as an artist, we come for -- oh, before we, you

Leon Golub These are some of the most ferocious images I've done. The early

Studs Terkel Here Siamese snakes, and again the two heads. Ambiguity.

Leon Golub That's right. Almost struggling against themselves, and it, this thinks is an animal, and it's an animal with a human head. It says something about our animal nature perhaps, you know, man doesn't have despite his rationality, total control over the choices always or even rarely, when sometimes says, all these early figures.

Studs Terkel "Thwarted", it not accidental that one, this one is called "Thwarted", "Thwarted".

Leon Golub And it represents

Studs Terkel Nineteen fifty-two, '53.

Leon Golub And it represents this -- with, it's really a enormous figure, not so much enormous in size as enormous in its components. Huge chest, uh, shoulders, thigh, yet they're cut off, they're truncated and they're shoved against each other. It's like it's almost trying to break out of its space.

Studs Terkel Something hit me as you were saying, Leon. You said the earlier paintings, early ones 25 years ago or so, were among the most violent you did. It's in the earlier ones.

Studs Terkel What does that mean now?

Leon Golub Well, it's a different kind of violence. The violence is internal. At that level. The violence is an introspective violence. It's a contemplative violence. It's a violence in which I take these, uh, ideas, and I move them around in a kind of internalized way, and I come up with an object which has these attributes to it. But it's not a violence which is extended in the social arena. In the later works, particularly paintings like this "Gigantomachy IV", or these paintings

Studs Terkel And that year was what? The three guys we talked about?

Leon Golub That's 1967. The violence is extended in time and space. It's not internalized violence with a sort of, uh, seething in the head as much as is violence extended spatially.

Studs Terkel So now, Leon, Leon Golub, we come to you, you, the artist, you the painter. You began, and it was a violence was internal, yourself the psychic violence, and now we come to you, the artist and also a human living in the world. And so it's hard for you to separate then, yourself and what happens outside the canvas.

Leon Golub That's true. And yet there is a separation that takes place. It's very difficult. The artist is responsible for the work, the art comes out of the work, yet something happened, there's an objective thing that takes place. Uh, whatever the conditions are in the making of the work of art, and people are extremely variable in these respects, nevertheless, and it comes out of the subjective conditions of the individual, nevertheless, once these subjective conditions have exerted themselves, they almost disappear, and what you have is the objective thing which exists in an actual social space which exists in art and art's time, and it has to be understood then as an object, and it hardly even matters whether the artist had this kind of obsessive quality or that because this piece is gonna speak its own language and take part in a real dialogue with its own environment. And in the sense, however, I tried very consciously over the years to objectify the circumstances, the condition, and the force of what I'm doing. And these latest paintings, they are probably the most specific in that sense. [pause

Studs Terkel I've turned the tape. Leon, we come to what you said a moment ago unto this fourth room, this last room in the Museum of Contemporary Art where the Golub retrospective, beginning tonight for Chicago audiences and viewers through September 20th. You said something about, as we look at these new paintings, new works of yours, something about even though the work is independent by itself, you, you're affected by the world outside, the forces of what's happened outside have to influence what you're doing.

Leon Golub Uh, this painting here is called "Assassins II".

Studs Terkel Now we come to the largest of all, don't we? This takes up the entire wall.

Leon Golub This is 10 feet high and 40 feet long. It has the, on one side of the canvas, there are soldiers in an armored car. Soldiers have M-16's, a machine gun, rifles, et cetera. On the right, there is what looks like and, of course, is intended to be part of a burning building, even some corrugated tin to the right, and there are some running figures, Vietnamese figures, who are running forward, almost toward the onlooker. They're running -- in a sense they're running out of the canvas onto the floor of the museum in one sense. The soldiers, however, are not running out, but are facing the victims. This is an attempt on my part to be extremely explicit, to take the generalized notions of stress and violence and struggle, which I had in the other large painting, the "Gigantomachy", which range from 16 feet to 24 feet in length, to take those conditions of struggle and to see if I could place them in an immediate political context and make it work under the conditions of my art and how I wanted to put it together. Therefore, it is extremely specific. The soldiers have uniforms on, you know, khaki green, hats, there are tires on the armored car. It's as specific as I can make it. At the same time, it is not a totally realistic thing, but I still use certain generalizing tendencies which relate to my other work. I also use the same technique which I used before which is to build up layers of paint so I tear it down. I cut it down the same way I did before. There are large, empty spaces in the canvas, which are supposed to represent a kind of generalized environment. I do something new in these paintings, which is that I cut out chunks of canvas. I tear the canvas, so the canvas is no longer a rectangle. I do that as a symbol of tearing, of cutting, of fragments, of the fact that I don't want the thing to have a finished look. I want to sort of in a sense move into the canvas. See, I want several things happening. I want these figures to move out from the wall onto the floor, which of course is not physically possible, but it's mentally conceivable. It's an idea. Therefore, I want this idea to operate upon the viewer. The figures are bigger than life size, the viewer is expected to be far from it, and to get close to it, and to have these figures almost fall on top of him from off the canvas, at the same time, I want to tear this canvas and rip it and destroy it in a certain sense, because it's almost farcical to do too perfect a picture of such a violent scene. I wanted to have these other aspects to it. If we look over here at this figure

Studs Terkel At the same painting, we're talking this huge context the entire

Studs Terkel Now we wander to what appear to be Vietnamese figures facing the guys with the machine guns and the tanks and the helmets.

Leon Golub Yes, these are, these are Vietnamese. And I was influenced by photographs of the Vietnamese people. This is cut out and torn.

Studs Terkel You're describing a lower part, something absolutely cut out.

Leon Golub And this figure, almost then, the figure above it almost tumbles into our space. Partly

Studs Terkel Above it is a Vietnamese guy in obvious agony. Men and women here, because my first impression, naturally, is this is My Lai, you see. This could be My Lai.

Leon Golub Or any one of a million incidents related to that kind of thing.

Studs Terkel As you have the bottom cut out, the bottom of this man's, his feet are cut out, this man, he's about to tumble onto me right now.

Leon Golub In a sense, yes. He falls into our space. He has this space, which is the art space, this is the real space. The two don't really meet, but he almost tumbles into our space.

Studs Terkel Unfinished, too, as the real event is unfinished, too.

Leon Golub That's right, that's a good, that's an interesting good comment, because I think of these paintings as unfinished, and I wouldn't want them to be too finished in the sense that this is 40 feet long, but this painting is unfinished because it could be 60 feet long or 80 feet long. There's no special point we're supposed to start and stop. It's part of simply the continuum of events. For a moment, we snap it. Like we might snap a photograph. We snap it for a moment, but it's just a piece of what this is.

Studs Terkel You go a step further, the Indochinese horror is unfinished.

Leon Golub That's right. That's right. And even if it's finished, it'll start somewhere else, because we haven't learned how not to do this.

Studs Terkel Something else here, too, isn't there, or am I just imagining? As I'm looking at this huge work you've done what year? When did you do this

Leon Golub Seventy-three.

Studs Terkel Seventy-three, just a year ago, and it's funny, it's almost like a, as the building is shattered in which they live, the shack, the hovel, it looks like a cross to me. Unintentionally perhaps but nonetheless I see a crucifix if I want to

Leon Golub Yeah, I didn't intend that, but okay, okay. You see it, then maybe it's there, but it was just intended to be two pieces of

Studs Terkel I know. It's two pieces of wood, it's almost as though they were a raggle tag of Christians facing Roman battalions. It's kind of funny. Is it Buddhists or whatever, but nonetheless, you spoke of survival, suffering and stress. Stress obviously here too. They're dying and yet there's kind of a not quite dying, they're raging against the dying of the light.

Leon Golub Well, they still retain the vitality of their emotions, you know, although it's like at a moment before execution. It's caught in that moment. In that sense, I was influenced by the My Lai photographs which show, uh, victims at the moment before they're killed virtually. Their gestures.

Studs Terkel At the very end of this huge panel, to the left of us, we see the soldiers and the modern technological weapons of destruction. And we see the Vietnamese people hit. The last person is a woman, there's a baby, and she looks like she might make it. I don't know. To tell the story. She might well be the narrator.

Leon Golub Well, uh, of course the thing is left unfinished, so, uh

Studs Terkel So it's now 1974 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, I'm talking to Leon Golub. And on the other wall, the wall next to it, there's something obviously unfinished. It is as though it were not a sequel to the My Lai kind of panel we just talked about seeing. Here is something uh, indif-- a new kind of militancy here.

Leon Golub Uh, this is a year earlier. This is nine-- this is 1972, and this is curious because it's

Studs Terkel It looks like a year later.

Leon Golub I see. Well, I, I try, there's a transition in a sense, between the figures on that big one we looked at before, the "Gigantomachy", the coloring and forth, in fact they're nude, largely nude, but they're kind of like nude to the waist because you get an indication that this man is wearing trousers and so on. They're less soldiers, they're more like irregulars, almost, the way that they are garbed or not garbed at all.

Studs Terkel Guerrillas.

Leon Golub Yes, that's right. They're more like that.

Studs Terkel Now, these are non-Western figures. I mean, they would be, perhaps they could be to me as I look at it, Latin American.

Leon Golub All right, or they could be American. I mean, it depends on how one wants to interpret it. The victims here aren't clothed either

Studs Terkel And they're shooting something.

Leon Golub And it can be of the same

Studs Terkel Group.

Leon Golub Group, same let's say nationality. Because these aren't really made as Vietnamese, you know. But they are treated as victims.

Studs Terkel So, this could well be Nigeria and Biafra, couldn't it? IT could well be Bangladesh

Leon Golub Yes.

Studs Terkel It could be the Ulster Protestant, Ulster Catholics, couldn't it?

Studs Terkel So here we have the irony,

Leon Golub So it's a generalized treatment. Although they're using specific weapons. Now, this is cut out much -- to a much greater extent than the later paintings.

Studs Terkel Now here you have a tremendous gap. A tremendous cut-outs, I should say.

Leon Golub And

Studs Terkel Separating the guys with the guns. And those who appear to be their victims who are of the same, same

Leon Golub It's the hole. In one sense, it's just a hole or tear. But in another sense, if one looks at it, it's almost like the shape of a tank or a boat, too, but seen negatively.

Studs Terkel Now, as you mention that, I hadn't thought of it. Now I retreat, and yeah, that could well have been a tank, couldn't it, or

Leon Golub I mean it's both ways. Again as a kind of possibility this way, or maybe it's a tank, maybe it's just a torn hole in the thing.

Studs Terkel Well, where does this leave us now? Leon Golub, as we wander through your pictures at an exhibition, this is your retrospective showing some 25, 26 years of work here, your beginnings in Chicago, and traveling through different parts of the world, and what's happened to your, your own works and your thoughts now. The artist today, 1974, you Leon

Leon Golub Well, in a sense, one is always between where one was yesterday and one isn't actually sure where one is gonna be tomorrow, or what one is going to make, you know, or what the new painting will look like, if I'm at all consistent with what I've been in the past, however, and I see no reason why I won't be consistent, since there no alternative possibilities open to me that I am interested in, there are no alternates that I am particularly interested in, I should imagine that I will continue on to the same tack and continue with what I think of as problems of stress, problems of time and how these things are placed in spaces.

Studs Terkel Continuity is always there, but there's always something -- you know, there's an old phrase used for certain artists like you, certain men like you, people like you. Always beginnings, never an end, never an ending, always new beginnings. At the same time, those beginnings had predecessors. Or precedents, one way or another. Classic art has never left you.

Leon Golub That's right. That's right.

Studs Terkel The human figure, by the way.

Leon Golub No, I am consistent in that respect. Certainly.

Studs Terkel The Leon Golub retrospective beginning tonight, at the Museum of Contemporary Art where we are right at this moment, beginning tonight through, that's 2-3-7, 2-3-7 East Ontario through September 20th, the work of a very powerful, powerful artist indeed. Any passing word before we say goodbye once more and then hello again, perhaps 10 years from now?

Leon Golub Uh

Leon Golub I just would might say that there is always, or typically there's a continuity in an artist's work. Therefore, anyone viewing these paintings can see the relationship between one period of time or one year and another year how an artist evolves. It's a great pleasure to be here. It's a great pleasure to be with you, Studs, again, and a renewal of our exchanges like this, you know? And a renewal of our friendship.

Studs Terkel Portrait of an artist as a young man, yes indeed, I was about to say middle-aged, no, young, because there's always something continuing all the time. Leon [pause in recording] That very point, before we say goodbye, Leon, that concerns you and me. Always continuing all the time. We speak of renewal. It's been 10 years since we've seen one another, so this, too, is part of the cycle of life. You and I are renewing an old friendship, not unrelated to the very nature of your art itself.

Leon Golub That's right. We're renewing in terms of current circumstances and struggles and conditions and the way things are today.