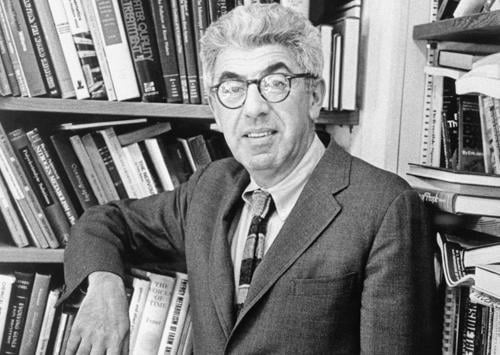

Interviewing George Wald, biologist and philosopher, on the hazards of pollution, the environment, and peace

BROADCAST: 1970 | DURATION: 00:29:04

Synopsis

Interviewing George Wald, biologist and philosopher, on the hazards of pollution, the environment, and peace. Wald talks about his speech at MIT "A Generation in Search of a Future".

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel We live in, you know, there's an old Chinese curse, "May you live in interesting times," and we do. We live in a time in which the instant philosophers on television form a long [unintelligible] who regale audiences with their attacks on the young and are celebrated; horrifying at the same time. We live in a time when "New York Times" columnists write a column about permissiveness and you think the man who wrote it is Billy Graham; it turns out to be James Reston. So it's so refreshing to hear a Nobel Prize winner related to the 20th century, and George Wald of Harvard, Nobel Prize winner for 1968 physiology and medicine. A recent talk at MIT brought forth an unprecedented response because perhaps he did touch the chord that so many felt, and were afraid to say and think, that perhaps the young do have something in their protests. Perhaps we are somewhat mad. Well, Professor Wald, I know since you, since the time of your speech, you've been on a merry go around. Everyone is asking for you to talk because you've obviously touched a common chord that hasn't been expressed.

George Wald Well, Mr. Terkel,it's a, it's a relief. It makes me very happy, I must say I'm the most surprised man in the world. I never expected that talk at MIT to have the response that it has had. But that makes me very happy, not because of the talk, not because it was mine, but because of just what you said. It means there are a lot of people in this country who are thinking those thoughts, want those things said, and want to say them themselves. I got a big mail these days and most of it is fervently approving and contributing to those ideas. So that's the big thing. And that gives me hope.

Studs Terkel As you were, the speech of yours, I read a reprint of it, and you spoke of the student protests all over the world and you say even though each is unique, each has its own problem, yet there is a common denominator. There is a common meaning to

George Wald them. Sure. We've reached a time, the like of which has not appeared before in human history in which the whole human enterprise is threatened, all over the world. The future of humanity is at stake. The whole human enterprise and that threat is felt almost unconsciously because the truth of the matter is, it's too awful to contemplate, it's too awful to keep in one's head when one says the words one immediately pushes it back out of consciousness. It's just too much, it's too much to live with. And so people talk about more ordinary things, less overwhelming things, and people try to tackle the smaller problems that look small enough someone can get somewhere with them. That's the way the students are. And that's the way their parents are, just exactly the same. So you find the students all over the world shouting for things many of which seem trivial, not the big problems, but they're the ones at hand that they feel they can tackle and do something about. And how about their parents? Just exactly the same thing. Right now there's a strong impulse in this country and incidentally being plugged by a lot of quite powerful forces, I think, to turn people's attention away, the people of this country to turn their attention away from their really big problems. The Vietnam War, the draft, the military industrial complex, an 80-billion-dollar defense budget and all the rest of it, and poor air and water and the condition of the cities and all the rest of it, to turn their attention away from these really big problems that are our problems, but are very, very difficult, very painful, one hardly knows where to begin with them. But there is something we can do, and just turning our backs on that whole pack of problems that are our problems and that have to be tackled and with great relief turn our interest to student unrest on the campuses, because that's something we can do something about. We can throw a few radicals off the campuses and really feel we're making headway, but that won't be making headway. That's no problem at all. The problems are much bigger and more difficult and those are the problems we have to keep facing.

Studs Terkel Those very ones and student unrest you see, of course, wholly related to the ones that we'll not face and they in a sense are making it articulate, therefore they make us uncomfortable.

George Wald Sure, they make us very uncomfortable because all those strange things that students are shouting for all over the world, and incidentally, may I say at once, we've had a series of protests and demands at Harvard. I'm not always in with the tactics used. But I want to say something: We thought some of those issues being raised by the students were pretty irrational, but we've learned better. In my opinion and experience, and I think that's pretty much shared not only by the faculty at Harvard but by the administration quite clearly by now, they haven't yet raised a false issue. Every issue they've raised has been real, but they are local issues. In my book and my hierarchy, you know, when I put down the priorities as I see them of the problems before us, when I've got to the bottom of my list I haven't yet gotten to the kind of issues the students are raising. They're local issues, some of which seem a little trivial to me. But the point is that they're immediate, they're their issues and they represent issues that those students feel that they can tackle and do something about.

Studs Terkel 'Cause this raises the point that you implied, too, in your talk, that very magnificent one, as to what the role of the university is really, when here are you, a Nobel Prize winner, yet some colleagues of yours seem more removed from the campus from what students are saying, than you are, you seem to be more in touch with them, so that the question of research as against the undergraduate school as to what is learning, what is, these are all involved, aren't they?

George Wald Oh, sure they are. You know, life is a complex thing, a person is a complex creature. And you don't just do one thing, you're a person. I'm a scientist. My scientific work is way up there in the priorities in my life. I'm also a teacher. Teaching is a big thing in my life and I teach about 350 students at Harvard, mostly freshmen and sophomores. They went on strike a couple of weeks ago. They thought, some of them thought, I ought to go on strike. But I was saying to them, "No, I can't go on strike because you see I never even remotely supposed that I had a boss at Harvard, that I was working for the President and fellows. No, if I struck, it would be against the students, and I don't do that." So I was saying, "Gee, anybody who wants to learn anything I can teach, I'll do it anywhere, on an empty lot, or, you know, you can't close Harvard. Harvard to me is faculty and students. You could close some buildings. But if anybody wanted to learn from me and I had something to teach, I'd meet them anywhere and go ahead and do that. That's among my top priorities. So that's the way it is. And when one is teaching, one is meeting people, students, those students have got very upset. That gets me all upset, and I try to figure out what's bothering them, and I'm trying to do something about that. But then, my heavens, I have a wonderful family at home. I'm a fortunate man at my age. I have two young children at home. They've just had their eighth and 10th birthdays and there they are. There my students are, as people, not just as students. And when I call for a better life for children, because I think that's the key to the whole situation, a better life for children, all children, all over the world. It's they I'm thinking of and all those young people all over the world.

Studs Terkel So you relate. Here again we come to Mr. George Wald, Nobel Prize winner, teacher. But more than that, you relate your research, your work, your students, your family, the world, they're not separated.

George Wald Not at all. It's one universe. That's what I try to teach my students in class. It's one universe and what the scientists can do for people now is to tell them because we're beginning to understand that it's a new thing. We didn't understand it nearly as well even a few years ago, but we're beginning and it's just a beginning. We're beginning to understand what that universe is like, how it came to be, how life comes to be, how man comes to be, what kind of thing he is, and what kind of universe he lives in. And gee, when you begin to understand that, it's a big thing. It's a so much bigger thing than all this tripe that's talked about; our weapons and the Russians' weapons and the Chinese weapons and our competition and communism, you know, when someone says communism to me these days, I say "Which communism are you talking about? My heavens, the Russians and Chinese right now are exchanging small arms fire across one of their borders, you know, which communism?" Oh, this is all a game.

Studs Terkel There's Tito, there's Castro, there's Dubcek, there are a

George Wald million and half. Oh, sure. And back of it all, the people all over the world want the same things we do. That's the big thing that people all over the world want just what we want. They want free speech and freedom in their lives and decent lives and some relief from the armaments and not being pushed into armies, all over the world they want the same things. The governments are engaged in a neat game of power and wealth and prestige. And notice how carefully the governments on both sides, on both sides, see to it that the people don't get to meet one another. It's hard for Americans to meet Russians and impossible for them to meet Chinese and then impossible even for them to meet Cubans. The governments see to that. Very hard to get through those screens that the governments have erected. And I'm an old guy. I can remember when there were no passports in the world. What a strange thing that seems now. Passports came into the world only after World War I. Before that, there were no passports. You could pick on any spot in the world if you only had money or other means of getting there, you went! You could go and live in those places. It was the open door. Remember that phrase, the open door? That was the open door in China. Their door is closed. Our door is closed. The Russian door is closed. The Cuban door is closed, and the governments are playing this game with our lives. So that's the way it is. People are the same the world over, young people are the same the world over, the students in Prague, the students in Moscow, the students in Havana, the students in the United States, they'll understand one another very well. The scientists in all those places understand one another very well. But there's a game of power. And that's shutting us all off from one another.

Studs Terkel Something you just said, Professor Wald, that the students, as though there's an international, the opposite of conspiracy, an international, the common meaning you're talking about. And of scientists, isn't it? That is, they understand something.

George Wald Oh, people are people, there are a little language difficulties, people are people, they want the same things all over the world, and a child is a child everywhere in the world and that's what I keep thinking and saying, a child, every child in the world is in our care. There are too many children, but one has to handle that at the source. But every child in the world needs to be cared for, and every child is an innocent dependent thing that has untold potentialities in it, and they all start good.

Studs Terkel In that speech you spoke about, since you are a physiologist in medicine. You spoke of, remember the origins, a man came, and suddenly there he is, the custodian of all: man.

George Wald Of all life. Of all life on this earth. We've gotten to be the dominant species on the earth and it's for us to take care of life on this planet. And I said, and I believe, it's the only life in the solar system. The solar system is our home and life on earth is the only life in it. I've heard about the possibilities of life on Mars, but I don't think much of them. Life is a pretty difficult thing to achieve and our planet is a good place to have it. But Mars is not, and it's hard enough to get it even in the good places so you pick yourself a bad place and it's pretty sure not to be there. So I think we have the only life in the solar system and we're the dominant species now. I'm glad that Mr. Hickel lately came out for the whooping crane, the whooping crane is almost gone. There are other creatures that are threatened, but we're threatening men.

Studs Terkel You know, since you spoke of man, he's in control of nature, of life of other men, this is man and this place we have, the one we know, you spoke of Mr. Hickel, this then leads to the question of environment and that which you face, the industrial military and our labor complex you describe, again, you speak of the trivia that has become so important made by others that is overwhelmed by what you see the possibilities are. You have the the attack on our environment and yet by men who use other phrases.

George Wald Yeah, well, we've taken a wrong turn in our culture and as it built up it's become very serious and, in fact, threatening, and all those technological developments that were promising and were actually delivering, to a degree, a better life, have overgrown and are now threatening us and spoiling our lives, spoiling our present lives and threatening our futures. And so we have to bring technology under control, and I think the principle is very very simple. You see, science and technology need to be sorted out in people's minds, there's a dreadful confusion about them. Science is concerned with knowing, with knowledge, and all knowledge is good. All knowledge always is better than ignorance. So that's fine. And one should go ahead in an unlimited way with that enterprise, it's one of the great enterprises I think, the two great human enterprises are science as knowledge and art as creative art, creation. Those are the big things and the more of both of them, the better. But technology represents the application of science to practical ends. And there one has to judge every aspect in terms of what society really wants, what it wants to do, and the trouble is that we've all been miseducated into accepting unthinkingly all new technology as progress and as an aspect of faith. An awful lot of people, including some scientists, go about with a feeling, "Why, of course you do everything you can." But of course not; You mustn't do everything you can, you must do only those things that seem right and good to you, and I think that's the simple principle, know all you can, but do only what seems right and proper to do. And society has to begin to do that picking and choosing, and it's terribly important that that picking and choosing of what's being done in technology is now the choice is being made at the production end, but that's all wrong, because at the production end it's guided by people who see their prestige, influence and power and status and wealth, and wealth, are coming out of producing those things that may be useless, that may be spoiling our lives our environments, that may in fact be threatening our lives. Now those judgments have to be made by not by the people producing those things, but by the people who have to live with them, by the consumers, and we're not used to doing that, and we're not set up to do it, and it's absolutely vital now that that's the way it begin to be done.

Studs Terkel So it's a matter of questioning technology toward what end, toward what purpose, this is really.

George Wald Exactly, exactly, always the question: Does this make life better? If not, don't do it. You take a thing like the supersonic transport. What's it for? We're told that it's going to produce big booms, these big booms are going to be very unpleasant. They'll wake you up, they'll make you jump. They'll produce cracks in buildings and all kinds of unpleasant things, but they're they're big and they'll go awfully fast. Well, is that the trade? They're also going to make a lot of money. There is even a lot of government money that will go into developing them. And so there are people, engineers, who feel this to be a challenge that they want to show what they can do, and there are other people who will make a lot of money out of those things. And it's a big deal. Prestige, you know, we'll have the fastest planes in the world, faster than the Russians, faster than the French, maybe, but very unpleasant to live with. So that's the place, that's the place to move in. And there are people moving in, but will we manage to have our voices heard? Will we managed to shut off that SST? Well, there's a chance, but that's a perfect instance. That SST is going to lower the quality of human life. Do we have to have it? Well, I think the people who have to live with that thing, who aren't going to be riding in it, you know, that are going to be subjected to the boom, they'd better shout loudly now. "No, we don't want those things. And if the French or Russians produce them, keep them away from us. Let them live with them." That's the way to talk.

Studs Terkel You're really talking about the clock, too, aren't you, you're talking about here's technology mindlessly used, or used by some few for their ends and not for the ends of many, and the silence, and time, you're talking about time, too, aren't you, now?

George Wald Oh, time's in it all the time. And that's where I'm a scientist again. But a, a man, too. I think as a scientist I see that human enterprise for what it is, it's a great thing and has a great history, a history that stretches back billions and billions of years and reaches into all the corners of the universe, the stuff I'm made of, gee, that's a big deal. The stuff I'm made of and you're made of, those atoms that make us up, the carbon, the nitrogen, the oxygen, those things were cooked in the deep interiors of dying stars. Previous generations of stars that died billions and billions of years ago, that's the stuff I'm made of and I'm proud of it. So I feel not alone that I begin to understand what a man is like and what kind of world he is and what is he is in and what his history is. But being a man, I I feel an identification with that thing, man and human the enterprise. I want it to work, I want it to have an unending future, you know, I want it to develop and I see the whole thing threatened now, by what? By some ghastly mistakes that are being, as it happens, the biggest business in the world now. Those things that are threatening life on earth and men. The biggest business in the world today, turning out profits, producing jobs, it's it's death against life. It's the death attitude against the life attitude. There are people who find their status in society and put their energies are all wound up with the business of life. And there are other people who find their status and prestige and influence and wealth in the business of death. And that's the fight that's on now, between life and death, life for men, death for men. And that's at the heart of what we're talking about.

Studs Terkel So you've been talking about in all of your talks, the common thread runs here from thoughts, feelings of Professor George Wald, life against death, that centuries, millennia, has made us as we are, custodians of everything we survey, and it's lack of imagination. Then, you're reasoning a lack of imagination being used at this particular moment.

George Wald Oh, I think what we need is to begin to recognize again what a man is. The genuine dignity and sanctity of human life. The traditional religions gave man a position of dignity and sanctity, and people ceased, began to cease to believe in them and to accept their view of men a good century ago. And for a while there was nothing to replace it. I find the sanctions for a view of the potential dignity and sanctity and ability of human life right in nature. My religious view, which has all those things in it, it's based squarely on nature, it has no supernatural elements, and I think that it's that, it's that view of man and what he can be, what he might be, that makes me so deeply interested in seeing it fostered and seeing life fostered and seeing it all go on, and I think as people come to realize, as they must come to realize now, that kind of thing man is, they'll feel that way, too, and it'll be life as against death that interests them.

Studs Terkel At this moment, at this moment, I realize you have other engagements and you're also, you've been pressed for time. This is, this conversation is taking place on the day of Dr. Wald's appearance at Orchestra Hall, people protesting the possible establishment ABM sites, even that itself significant. You're speaking of the trivial, the lack of imagination that what separates man, and the overall thing that makes man identical. Not -- Each one unique, and yet has a common thread. And at the moment we live in this incredible time of going either way.

George Wald That's very strange. You see, there's another aspect, and as you mentioned time before, yeah, time is in it, all right. It's the short-term profit and prosperity against the long-term disaster. And you see that's what brings the young people in, their parents are shooting for that, those short-term returns. You know, all of us have been tricked into this insane view that the intervals between the wars are the normal times and we concentrate on them and everything is nice and cozy until the next world war comes and then, this next one's really going to be close to ultimate disaster. But the last one was bad enough, and the one before that was bad enough, and that's it. They're coming now in something like a 30-year cycle. So one is due shortly. And meanwhile, one can have great prosperity, and, you know, the house in the suburbs and the two cars and you give your kids expensive educations. But those kids, they have to have the long-term view because they're just getting ready. You know, what's that life going to be like that stretches before them? They don't see it. I don't see it. The experts don't see it. That's terribly bad. And that's it. We have to take the long view. This short-term stuff is for the birds. There are an awful lot of people who feel dependent by now on that 80-billion-dollar defense budget, but they've got kids and that life ahead looks pretty stark and empty for their kids, and that matters, too.

Studs Terkel Dr. Wald will be talking about, he referred to a senator, a distinguished southern senator who spoke one, if we do survive this, he trusts the Adam and Eve will be American, and Dr. Wald as a Nobel laureate, said, "I think this is criminally insane." And, of course, there was reaction from the young. So again, life against death and he quite obvious is on the side of life and sanity. Thank you very much, indeed. I wish there were more of you.

George Wald Well, thank heavens there are more than I dreamed. I think there are a lot of us by now and we'd better just press for more life.