Florence Scala discusses her friendship with Jessie Binford of Hull House

BROADCAST: Jul. 18, 1966 | DURATION: 00:51:26

Synopsis

Even after Jessie Binford left Hull House due to its demolition, she corresponded with Florence Scala through hand-written letters. Scala learned that Binford was a country girl who lived in the big city of Chicago. Scala reads some of her letters from Binford. There is also an excerpt of Jessie Binford.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

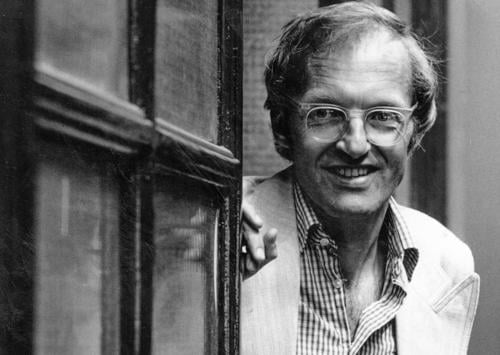

Studs Terkel And Jessie Binford died at the age of 90 at her hometown, Marshalltown, Iowa, July 9th 1966, buried in her hometown Tuesday the following week. Her best friend, I'm sure her closest friend during the last years of her life, was Florence Scala. They had battled together so gallantly, though the battle was lost. And that's a question, to find out was -- what is being lost? And Florence is our guest this morning. Florence, who won't say this but I shall, has in her way become a leader, a word that perhaps is misused, misused so much these days, but someone in her community -- quiet in the past, just a housewife walking her dogs, as she recalled once in a prior conversation, during a [prior? private?] conversation -- out of the battle to save an area that is no longer, as she and Miss Binford came to know one another. And I thought, Florence, we just sat by for a moment and heard Miss Binford during the time I visited her--

Florence Scala Mhm--

Studs Terkel Last autumn in '65--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel September, [remember?]. I asked her the question -- she had lived for 60 years, close to 60 years at Hull House, a friend of Jane Addams -- I asked her the question about the possibility of returning, what her feelings would be and--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Do you think you would find yourself a stranger in Chicago now?

Jessie Binford I can't imagine where I would want to live in Chicago, if I were going back there, after living in Hull House. I I can't imagine. I just can't imagine any place that I wouldn't feel more isolated almost than I do here. Much more. Now that, perhaps, is just personal, probably isn't have anything to do with Chicago. But I think big cities have gotten to be just terrible, terribly hard on people and terribly -- There's some neighborhoods left. But and, of course, that's another thing today that I think neighborliness meant so much to people as we all grew up. Now there's so much change all the time you're -- I do hear some discussion here about the industry today, how for instance here and now in one of the big industries they're establishing branches and men who have their homes here and even younger men who have come here to live, have their homes and their families here [just at a moment's notice?] and all are sent down to the new, to Texas, to the new branch. They aren't sure of of staying any place. I have heard people talking about that here, because the industries here are establishing new branches and people have to go.

Studs Terkel Come back to that transient quality and, don't we, that increasing transience of life.

Jessie Binford Exactly. Exactly.

Studs Terkel There's that building that your father built, almost, a building--

Jessie Binford Yeah.

Studs Terkel Almost 100 years old--

Jessie Binford Yeah.

Studs Terkel Still stands as something of permanence--

Jessie Binford Yeah.

Studs Terkel In the transient qualities entering even the city, too.

Jessie Binford Yes, yes. And it's very hard on families, I think. I know. I heard someone discussing that the other day, someone who is now being sent way down to southern Texas. They thought they were established here for life.

Studs Terkel So this building where your father may be an exception one day in this city.

Studs Terkel In Marshalltown. So Marshalltown, then it's contagious. This may be getting what Chicago has--

Jessie Binford Yes.

Studs Terkel This transient quality.

Jessie Binford Yes.

Studs Terkel The trees symbolically may go down here, too.

Jessie Binford Oh, they're going, they are, they're going down here, too. And nobody seems to be able to stop it. And nobody, I don't know whether nobody cares or not, or or whether we've just gotten into a, into a period when you think you had to accept these things. I I think it's more that, that, what's the use of trying? Everything's changed and everything's changing.

Studs Terkel As we listen to Jessie Binford reflect about people, in a sense giving up, the changes taking place, what's the use. Florence, your thoughts on hearing your friend?

Florence Scala Well, I -- they're always so filled with being so near her. I couldn't help thinking at the beginning, Studs, how true it is although we wanted her to come back so badly when she'd left Chicago, we knew that she'd never be alone there. That she did have many friends in Chicago besides us and she'd not be lonely, however, before she left the city she couldn't bear herself, she couldn't bear to leave Chicago so quickly after she'd been evicted, you know, from Hull House, that she stayed at one of the hotels downtown, and I'd see her every day. And every evening we'd walk down Michigan Avenue and, you know, though she'd been in the city all this time and had been all over the Loop, while while she was living on Michigan Avenue she absolutely felt out of place. She was uneasy about walking down the street even. It all seemed so big, you know and it ju--

Florence Scala Impersonal and and she was really isolated among all those people there, so that the loneliness had already crept in. And although she's she certainly faced up to what she had to live with in Marshalltown, the last years, she was a very lonely person. She was separated from, not only the kinds of people she knew, but from ideas that she she could--

Studs Terkel Mhm.

Florence Scala Toss around. And and in that small town, in Marshalltown, except for the people that came through the hotel, she was really confronted always with a pretty conservative, very narrow point of view.

Studs Terkel Or these young, or the exceptions, these young kids now and then that she met. The young ones--

Studs Terkel They were the ones that kept--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel Her alive, really, weren't they?

Florence Scala Yes they were. And when she talks about her concern about change, I don't think that -- she was always a radical all of her life. I think that that's the thing I'd like people most to remember about her. That she was really a radical, although she was a gentle person with great dignity, she was always bucking the system, because she she knew that some -- you know, that life had to be better than it was all the time. And she very rarely got into any kind of a rut. She did at times, but she -- her ideas were always moving ahead. And this is why she was the kind of a person who was a real joy to be with, you know, regardless of her age. I would have loved to spend all of my life with her completely as a friend, you know, if I were -- she would have been a perfectly satisfying friend to me, if she could be the only one I had for the rest of my life. But she, but she hated to see us give up what, as she said with you, last time, were those values, the -- what what was important about the past to retain in the present. And she saw that changing. And we feel it too.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Florence Scala We feel this. This is I think what disturbed her most about not being able to do anything about it, somehow.

Studs Terkel Being overwhelmed by huge organization, corrupt, but huge.

Studs Terkel And the feeling of impotence. A thinking individual, what can I -- whether, she referred her to 800 trees of Jackson Park that she'd heard about--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel After she had left, as well as the tearing down of the Hull House itself--

Studs Terkel In the neighborhood but the feeling of, what can I do? You know, she refers to this kid who worked at the place at the Tallcorn Motel in Marshalltown--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Who chose one book in her library. He's a -- he was a retarded kid, but the title attracted him: "What Can a Man Do", the book--

Studs Terkel [Milton Mayer?] of Milton Mayer, and what can a man do which is, of course, is the question of the now isn't it?

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel And always this disturbed her, the giving up, the giving up.

Florence Scala Mhm, it did. And she never really had answers, and she was always seeking. She was a seeker. See, she was part of that group of people who never gave up seeking and when confronted with a question, wasn't always sure that she could have the answer to it. And and so she had -- I don't know that she could even answer adequately for that young man, the question you raised: What could a man do? What can a man do?

Studs Terkel Several of -- I know you have some letters -- you and she corresponded aside from your visits to her, seeing her, during the part of the interview we hadn't played she refers to Florence Scala, "a city girl being in the country," and your love for the trees.

Studs Terkel And she didn't want to tell you, that would take a -- you took some walnut seeds home and she said, oh, you'll love that, but she didn't have the heart to tell you that it would take years for them to grow [laughter].

Florence Scala I know, she let me fill a whole bag. I didn't even know what they were, laying down there in the grass, you know. We'd gone to this beautiful park, I don't know if she described it to you. It's a great big park that her father, her family, had given to the town of Marshalltown. Their farm was quite large and they decided that they would give half of it up. It was a place where they used to take the cattle to to graze. And there were these huge trees that she just loved. She just loved the trees. And I saw these things on the ground and she told me they were walnuts. I'd never seen them like that, you know, so I picked them up sh- and I said we'd plant them in Chicago. Well--

Studs Terkel In the visits to her and seeing her, there was also this correspo- by the way we should point out that Jesse Binford's hand, her handwriting at the age of 90, there's this, the firmness, there's a -- naturally, this is not typed. This was handwritten and, "Dear Florence", and you have a variety of letters, perhaps you could just, because in these letters, too, her thoughts are--

Florence Scala Yes, well, this one--

Studs Terkel Expressed.

Florence Scala Yeah, she never wr- she was often lonely and very discouraged sometimes but, this, I think this letter exp- expresses a facet of Miss Binford that makes people understand why it's easy to love her. "Dear Florence, when your last letter came I thought that since," June 15th 1963, that was when she left Hull House, "that we've both been going through much the same deep thinking and emotions: up and down, hope and courage. But at times almost despair, sort of lost in the maze. The one thing recently which seemed again to lift me out of the depths are Pope Paul's words at the United Nations." She has here the League of Nations.

Studs Terkel That's interesting, she said the League of Nations.

Florence Scala Isn't it? Yes, mhm. "One of the greatest appeals I have ever heard ringing out so clear and so true, and including John Kennedy's words, 'mankind must find an end to war or war will put an end to mankind' [sic]. [All so? Also?] true, even without war, of the kind of world we are making. I loved it because he, like Miss Addams, had no condemnation of individual or nations. He only opened wide the door to to that future that can be and in his infinite faith in all mankind. Did the world stop and listen? Not one single comment or reference to it have I heard here. Haven't we time today to stop and listen? Even for one hour?"

Studs Terkel This is a 90-year old woman, in this instance about 87, 88 so we speak, what is age, what is being old, and what is being young? So in Marshalltown, which her father founded, and they all referred to her, by the way, respectfully as Miss Binford or Miss Jessie--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Nonetheless she was the only questioner in that town.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Florence Scala Really. She really was. When she got there, after she settled down a little bit, the the people, the important people of the town, came to visit her, you know, to try to get her established in programs that they were getting underway there to build a YMCA and get her, you know, but she just simply held them off and didn't and wouldn't get herself involved in any of the town's programs until she was there long enough to see in what way they were moving and in what direction they were going. She was concerned very soon after she got to Marshalltown to see, for instance, that the small Negro community really was very much the same way still, you know, that the events of the recent, very recent past hadn't touched Marshalltown--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Florence Scala Yet. She -- so she held off from becoming involved with any of the established leaders of the Marshalltown community, and I think they kind of viewed her as a sort of an oddball--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Studs Terkel Even though they paid her respect in editorials and papers, she was this elderly lady whose whose family was one of the first families of the town. Nonetheless, well, that's Miss Jessie, you know.

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Not realizing she was representing something of now and tomorrow, she was trying to tell them.

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Florence Scala And then, you saw probably while you were there how she had her best associations with the people who worked in the hotel.

Studs Terkel Yeah. Very definitely, yeah.

Florence Scala The maids, the desk clerks, the waitresses. There was no difficulty there, you know, communicating.

Studs Terkel Yeah, yeah. They all knew her. In fact, when I first came there, when I came there for the interview in September of '65, the clerk said, "Oh, she's expecting you."

Florence Scala [laughter] Yeah.

Studs Terkel And when I went for a cup of coffee in the coffee shop there, the waitress there said, "Oh, I know who you're going to see." You know, and their enthusiasm for her, whereas, the establishment of the town looked upon her, oh gently but--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel As you say, sort of a kook.

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Sort of an oddball.

Florence Scala Oh boy, you can imagine what she went through during the presidential campaign, you know.

Florence Scala It was real wild there because they had great big headquarters, the Republicans did, in town and and I I never knew her politics but I knew she was, at that time anyway, not a Republican.

Studs Terkel But she always tried to arouse discussion, and could ev- she said she was the, in fact sometimes she stopped talking, she said, "I talk too much." That is, they would -- they didn't listen.

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel Although, a who cares quality, who cares quality was part of it, too. She questioned the building of the big gym and the teachers being underpaid--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel You know, and and at that, too, they laughed.

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel So [at all?] isn't it, did you notice in the conversation whether, in the conversation, the correspondence -- she was also connecting, it seemed, all the time, Marshalltown and Chicago? That the same sort of ailment was affecting both.

Florence Scala Yes. Yeah. She she she did that, and she did that in some of my letters, too. Or or she said that the pattern was still the same, that this, this thing had infected all of, all community life here in America and really, of course, this is the thing that disturbs all of us, too, the same sense of frustration we feel in the big city, she felt in another way there, and she could see it with the young people there because even there, where a fairly prosperous town when everybody working, the young people didn't stay. They moved on. And the fascinating thing about that town to me, is that the population has hardly varied over all these years. It's stayed pretty much at that 29,000 level, which really means that it's re- not really growing as a community.

Studs Terkel Nor is it diminishing, intere- this is interesting--

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel Because sometimes it would die out, you know. If only--

Studs Terkel But, no this is as is it goes on, and so somehow it seems people, by the calendar, grow older, but there is no growth.

Florence Scala No.

Studs Terkel It's just, it continues, so it almost seems like a limbo town.

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel But throughout she was saying Marshalltown, Chicago, the no walking. I hear people say we take the automobile to the supermarket three blocks away. She was the only walker in the town.

Florence Scala Mhm. Yes, yo- and this business about the trees was very real because on Main Street they had the big trees, which are still down that part of Main Street where their family home is. And it just made her sick when they tore down those trees. Now, of course, down the part of town where where the house is, just down from the hotel, the big trees are still there, and Binford House, which now belongs to the town, now -- she's given it over to the town -- even her own family tried to persuade her to have the building demolished and maybe the town could use it for a parking lot. Well boy, you know, she almost, she would never have--

Studs Terkel Oh, is that -- I wasn't aware of that.

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel Oh, there was that approach made?

Studs Terkel think she'd tell you that, yep. There was that -- they wanted to tear down the Binford House.

Florence Scala The approach was made to the family, and conveyed to her that perhaps that might be the best use for the, that location.

Studs Terkel They probably could have said to her, "Well, Miss Binford, look, you've lived in Chicago many years now."

Florence Scala You you know the need.

Studs Terkel We want to learn from your city.

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel The Garrick Theater was an old building, was torn down, became a parking lot. Why not the Binford house that her father had built.

Florence Scala Yes. That she really loved.

Studs Terkel She told you that story many times of her father building that house.

Florence Scala Yes, mhm. And she loved that house. She really loved that house.

Studs Terkel Building and building--

Florence Scala She--

Studs Terkel Of course, Hull House and Binford House, both Binford House solid and strong, Hull House was solid and strong, as you you said several times very -- how hard it was to tear that down.

Florence Scala Yes, mhm. Yes I--

Studs Terkel By a demolition crew. What are some of the other letters that you have from Miss Binford?

Florence Scala Oh, well now the, they're little, just little bits here and there, how -- this is just a little sort of gentle thing. She says, "Dear Florence," we'd talked on the telephone together last night and and the night before and she said, "forgot one great event last night: The first robin to be seen here was today in Ruth's yard," that's her sister, "and a few hours later a cardinal and some dear tiny birds, Cedar Waxwings, so the world moves on in spite of human control. And as I finished our visit, our great, almost full golden moon was rising in the eastern sky." I mean, you know, we're always talking about how people don't have the time to stop and stare or or look or pay attention. But many of the letters I have, have this little, just a little note of the things she's noticed that have given her pleasure. And I thought that was--

Studs Terkel Yeah, you speak of the time to stop and stare, as she did.

Studs Terkel Always did, even in the middle of her battle for the young in the city of Chicago with the Juvenile Protective Association, which she helped found, [always?] there was the robin. Which brings to mind, Florence, a certain incident. Do you remember when -- with the tearing down of Hull House, the Japanese Elm tree?

Studs Terkel That dealt with sparrows and trees. Could you recount that moment?

Florence Scala Yeah, this beautiful tree that had been planted by Mr. Hooker, who used to live at Hull House, and was a member of the City Club of Chicago and was very interested in city planning and beautification and all this business. He had planted this tree and and it grew right in front of her window in the Hull House courtyard, and it was huge and it flowered in the spring. Not often do they flower, but this flowered in the spring, the most beautiful white fra- fragrant flowers. Right after Miss Binford left, and I was happy that she herself had never seen it, they came with the claw and began to rip the tree apart, you know. And of course it was dreadful, Studs, because lots of birds lived in all those buildings, you know. So they were just sparrows and starlings but the flurry of birds and pigeons [just all?] over that tree and over those buildings. And a tree being clawed from the roots by this, the huge claw that they have for wrecking was really a terrible sight and the engineer, the Hull House engineer, and I were standing there and even he wept. I mean, it was really a dreadful thing to see and she loved that tree very much. She sh- when she left the building, when she finally left Hull House, she never came back again although she did stay downtown those weeks, you know. She just couldn't.

Studs Terkel She didn't want to see it, didn't want to see it.

Florence Scala No, she wasn't able, really, to come back there to see that.

Studs Terkel You know, one of the sequences in "Grapes of Wrath," of Steinbeck's "Grapes of Wrath," is when Ma Joad, after they're -- have to go leave their homes in Oklahoma and head to California, and the bulldozer was breaking down the home, shacks though they were in which they lived, she would not turn back and look, Ma Joad. "I don't want to see it. We're headed to California, ain't we?" So in a sense Jessie Binford not going back to Hull House.

Florence Scala Yes. Same thing. The real same thing.

Studs Terkel You you spoke of the tearing down, how this all related, that's why she, even though it was another area entirely, the Jackson Park, 800 trees that went down to widen the outer drive. Stuart Chase and John Hawkinson and Dorothy, not Barber -- what's her name -- it was Hayes, were involved. They recalled the birds, how the birds, frightened, flew away.

Studs Terkel And [never came up? never came back?], just flew away. And so here, too, the sparrows and starlings.

Florence Scala Yeah. It it's a very sad sight to see this. You see it happened in the spring when the birds are nesting and some young birds were being hatched. It -- well was early summer, very early summer, and this is what was so dreadful because I had taken a -- before we left, I decided to take pictures and I went over all the roofs that I could, traveling from building to building on the roofs, and I came upon many of the pigeons near their nests with little babies in them, see, and the sparrows and I just knew, you know, this was really going to be havoc in the in the next, in the days that followed. And what happened when they tore the tree, of course, was just this. And it was the the the birds just in despair over what was happening.

Studs Terkel What were the feelings? You talked to the men, you knew some of the guys in the demolition crew, they're from -- what was the, here's a guy doing this with the claw, or the wrecking ball, or the bulldozer? What -- when you cried out, what were the reactions of these guys.

Florence Scala Well, they didn't laugh or make fun or anything. They, I don't, I think that the men who were around were, really didn't like doing that. I'm certain of it. When they were destroying some of the buildings just west of Miss Binford's building, the const- head of the crew, the demolition crew, came up to her apartment and strung huge canvas over the building, so that she need not see it.

Florence Scala And also to protect it from any flying debris, you know. But more, this really was a blessing because she wasn't able -- unless she went out of her way to go into another room and look out the window -- she wasn't able to see that thing going down next to her, the Jane Club going down. And you know, Studs, can you imagine, she stayed there through those days watching all the other buildings go down around her. What it must have meant. And I tell you, I I guess I'll never forget her face at that time. She was just beside herself, and yet she never broke down. I never saw Miss Binford cry. Saw tears welling up in her eyes, but I just never saw her cry. She just never broke down. You know -- well, she's just a, just a perfect touchstone for lots of people.

Studs Terkel What are some more of the letters that you have? I know there was this -- the letters themselves perhaps could one day be perhaps part of a book.

Florence Scala Let's see now. This one--

Studs Terkel The handwriting is amazing.

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel Always that strong, firm hand of this woman in her very late, late 80s.

Florence Scala She talks about her concern, partly in some of the things we've talked about before. This is just an excerpt: "Never as long as I can remember have we ever been so overpowered. We were almost like children," she's speaking of our experience in the court thing. "We were not, were we not when we went to Washington, and in such confidence and faith. After we had exhausted all other local and state governmental officials and departments, really, so few people realize what we learned. I still think that our one, great white hope was John F. Kennedy. With time for him to slowly, of course, develop his vision of what must and could be done, and who is there today to carry his torch? Our president knows this all too well. He may be going so far and so fast that the people of America will catch up with him and call a halt. But I'm not so sure".

Studs Terkel Well, she had this, also, this feeling of despair, didn't she?

Studs Terkel Through the years great confidence, you know, for most of her life. Great. And then, finally, came a moment when she felt maybe no.

Florence Scala Yeah, that you really couldn't do much. She's troubled here about the war in Vietnam a great deal. And it was at the time that there were protests were beginning all over the country and that it didn't seem poss- it didn't seem possible then to change the course we were on, and she ties this in with the feeling we felt, you know, when we tried to alter the situation here in Chicago.

Studs Terkel Well, this is an interesting point again: Marshalltown, Chicago, the country, the city, the city, the area -- all related. When you and -- Florence Scala, our guest, when Miss Jessie Binford and Florence Scala were working together to save the area and Hull House. The overwhelming and overwhelming opposition that just just like a tidal wave, you know--

Florence Scala Mmm.

Studs Terkel A battle that, but overwhelmed. At the same time, she sees it nationally, internationally, too.

Studs Terkel The same overwhelming org- and, what can a man do?

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel A woman. And yet, in that battle something happened. Like, I know there's a girl. I'd changed her name, I called [Ann Ramano?]. You know her, she works downtown, sits juries. She's sort of a deputy sheriff, a young widow with six kids.

Studs Terkel And it's quite marvelous. And she was saying something, "maybe we lost and now we come to this. Maybe we did but, something, I found something out about myself", she said. She's quite funny.

Florence Scala Oh, I know Ann.

Studs Terkel And she's got marvelous. I thought I wouldn't use her name because she's working for the city, for the county. But she said, "you know, when I heard Florence Scala she turned my motor on," you know, "and these, and suddenly there am I." She says, "Well, I'm not going to stand by while the whole area or others are fighting my--" And next thing I know," you know, she's not a widow actually she's divorced, you know--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel And has six kids. "There's too much mom-ism in the house, I want the older boy to take over. But what happens, I come home one day, with Florence at City Council and I guess I was on television. And there am I, of all people, making a speech and the kids go, 'hey Mom we saw you there', you know. And she says, "Well, suddenly I realized, wow, where did all this come from"? She says, "Well, God. I got a compact with God," she says, you know. "He and I we we kinda talk to one-". I said, "well, you had something to do with it too, you yourself." We'll call her Diane for the moment--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel You, yourself, yo- said, "Well, I don't know, because when I stepped up against FioRito" -- not FioRito -- yeah when you--

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel When when she first challenged FioRito -- Florence Scala, by the way, ran on the Independent ticket for alderman, first Ward, and battling both parties got 3200 votes. [laughter] At the time, the man who beat her was Parrillo, but the original candidate was FioRito who didn't live in the ward, and he was challenged by Diane in this. She says, "I stood up against them," them being all the powers over there, that were pretty rough.

Studs Terkel She says, "and their mouths popped open".

Florence Scala I know [laughter].

Studs Terkel "And then something happened," she said. "My voice was stronger than I ever thought it would be. It came out. So it must have been somebody. It must have been the man upstairs." I said, "It might have been you, too, and Florence, and Jessie Binford, too." So, we come back to that sort of residue that is good, out of the defeat.

Florence Scala Yes. Yes and yeah, that that this isn't, this is true. And the thing about Diane that I think is is a nice thing to know, Studs, is that she wasn't necessarily involved. She lived three blocks west of the Harrison Halsted area, and she need not have bothered at all to get involved, but she did. And I mean, she saw that that it -- you couldn't isolate one community by a street or an alley that divided--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Florence Scala You know, one area from another. And she's -- and it's -- we're all there still in the same general area, you know, I mean we haven't -- nothing has changed so much, but a lot has at the same time.

Studs Terkel Sort of like an island, isn't it, in a way?

Florence Scala Yeah, it's like an island.

Studs Terkel On one side the Circle campus, another side the hospital complex, another side high rises. Those, in a sense, like an island.

Florence Scala Mhm. A real challenge for this city, if it really wants to look at what some of these problems are in in an urban area, see.

Studs Terkel We sort of dot this conversation with excerpts from letters that you're reading and then I'd like to ask you a--

Florence Scala Alright.

Studs Terkel Question about your first meeting with Miss Binford. Again from Jessie Binford, Tallcorn Motel. The stationery itself is rather interesting with a little sort of design there and her [unintelligble].

Florence Scala I don't know that this says so much but it kin- again, to give you the the factors of her up and downs, she asks in this letter, "Do you ever have a day on which you've lost, it seems, all your philosophy and faith and courage and you seem lost? You know not only, you know not why or how it comes, but I don't have this often but today was one of those days. You can't some way, somehow pull yourself together. My sister called and asked me to go with her and a friend out to drive around and see the flooded country", this was last spring, "and then have an early dinner down at Stone's. But I was just not in the mood to go anywhere or be with anyone. All day I meant to write you, but I I wasn't able to do it until I, until tonight. Perhaps I came out of it all when just after I'd gone down to have a little supper, all the lights went out all over town and we were in darkness for an hour. And long before that, the last of the evening twilight had gone, when finally someone found some candles and you eat, if you're fortunate enough to have something. The kitchen here was completely blacked out. And so the day endeth, and half of Iowa was dark from the flood damage, they say. But it took me out of myself and that broke that mood." Well, you know, I often think of myself in in despair like that and somehow I I just don't -- I very often am able to pull myself out of it, you know, just perhaps still keep sulking or just keep withdrawn and concerned about myself only. But what I found in her was the way she was able to, at her age, mind you, when when you do become emotionally weary, was the way she was able to surmount, to try at least, to surmount whatever was really troubling her inside. She did this so well. And, you know, when she talks about Jane Addams being the kind of a person who rarely condemned, she herself was like that. Very much like that. And she rarely despaired so completely that you you got very worried about it, you know.

Studs Terkel So, even though there were these moments that one has, and she had reason, in these moments something would happen outside herself.

Florence Scala Yeah. And and she recog- and she allowed herself to be pulled away from herself, which was very, which was her charm. She talks here about that WIL meeting--

Studs Terkel This is the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, which Jane Addams founded and which Miss Binford was a member.

Florence Scala And just this little bit, because it has to do with Mrs. King. She says that she felt about the league that they they were stronger in their purpose and in their conviction than they had been. And they were a group that didn't have much money, she felt, and they spent so little of their time trying to raise more. They're right, she feels, in her in her in in their outlook, "Florence, as Jane Addams was. I can imagine how hard it is for Mrs. Martin Luther King, as it is for him, to come north and justify, but he has so sincerely, what he, so sincerely believes in doing now. Think of what he's claiming to overcome. Suddenly it seems to the majority of people, north as well as south, that it's too soon. And yet how long, how long it has been, it has taken us all, to make much of a beginning and think what he has done." So, her commitment to the the movement, the Civil Rights movement was a total one. And and she, you know, I don't know, I can't really remember what was happening at that time in the spring of '65 down south, but I think that they were -- that King must have been confronting something down there, and his wife was here making--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Florence Scala That talk, you know. And he was at that time still in the north being criticized for his activities. She, she never wavered. And you know what's interesting about her too, Studs? She was not so terribly disturbed, at least at that time, about the very activist groups in the movement, because she somehow felt that you needed them there. But that one had to -- she would not have agreed with any kind of activism that would lead to any kind of violence or was isolating the communities, black from white. But she felt that one could hardly help but expect that there would be a very strong militancy within the kind of a revolution like this. And it didn't upset her quite as much then as it seems to have upset a lot of other people. I don't know.

Studs Terkel Again you see her her sense of wholeness--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel With the world. Her sense of awareness -- relating everything, one with the other, and putting herself to this quality -- putting on someone else's skin, and this capacity she had. Again, age being wholly irrelevant in this matter. And it it -- she was involved in, complete involvement, just as you spoke of Civil Rights, peace, everything, all the trees, and the sparrows, and the starlings -- all related.

Florence Scala This is the last letter I got from her, the very last letter written. I talked to her after this letter was written. This was about the 9th or 10th of June and she sends, she sent me lots of clipplings[sic] clippings, and she, this was just disturbing her, you see.

Studs Terkel "Iowa state flower struggles to survive." This is from the Iowa paper, Marshalltown paper, I guess.

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel "Wild ro-" and the subtitle is, "Wild roses last stand against sprays and urbanization."

Florence Scala Yeah, I guess the wild rose is the flower of Iowa, you see. And, she -- this again was around the time, it was a sort of an anniversary for us but coming close to the time that, you know, the anniversary of her leaving the city and she writes, "These are still days of memories, are they not? And after an especially gloomy day here, for many reasons, I just read in the paper, the wild rose, and I thought how, in all the years of growing up here how we loved, and even now, in as we drive around we say, 'this is the place we used to come to see the wild rose'. The first year I stayed in Chicago at Hull House from Christmas until June, on the train all the way out I just looked for the wild roses along the railroad tracks. There are so many, there so many grew then. They never lived long if you picked them, and took them away from the sunshine and the wind and the weeds, even. They seemed to belong everywhere, as we mere human beings should be. They knew no segregation, no org- org- organization in gardens, or greenhouses, or gardeners. They had no status. No so-called important improvement for everyone." You know, she's again talking about these things that she was talking to you with, I think, that you opened the program with her concern for losing the things that really have meaning, you know, the flowers [unintelligible]--

Studs Terkel She was never, by the way, let's make it clear that it wasn't a question of being opposed to progress--

Studs Terkel Not a question of being opposed to change. On the contrary, thusly, her interest in the in the Civil Rights revolution. But the idea of losing that which is eternal in value.

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel The tearing down of a certain kind of good building for a parking lot. There are some buildings that should be torn down, of course. But talking with those that do connect us with past. This was always her--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Her theme there. Yo--

Florence Scala Well--

Studs Terkel Beauty then, is it not?

Florence Scala Oh--

Studs Terkel Would you say that it was really a search for beauty?

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel All the time, beauty.

Florence Scala Yes. You see, she really hated what was ugly in life but she didn't turn away from it. I think this is what those women had. They hated that slum condition, they hated the ugliness, the filth. But they didn't run away from it. They didn't turn away from it. And they didn't hate or or you know, feel [eeewww?] about anybody who was himself unfortunate enough to be any, you know, in any, anywhere along in in life.

Studs Terkel Florence, you said something: 'those women have'. You say, 'those women'. Now whom do you refer to? There's something specific about this.

Florence Scala Oh, yes. Well I'm referring to, of course, Jessie Binford, and Jane Addams, and Dr. Alice Hamilton, the sister of Edith Hamilton, you know, and her sister, Nora Hamilton, and the Abbott sisters. That whole crowd. They really, you know, they really, [laughter] they really changed things.

Studs Terkel Which leads to a question, Florence. I'll omit you for the moment. I think you are part of this tradition. Are there, do you find that that kind of woman -- and these are women, by the way, who need not have been part of this battle.

Florence Scala No.

Studs Terkel Because they all were more or less well-fixed.

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel Economically. But they voluntarily were part of it. Do you find less of this in your experiences?

Florence Scala Yes. That is the sadness, you see. They had, they had a true feeling of of a responsibility that was terribly important and they acted on it. I I I rarely, if ever, see this kind of thing today in in city life. The closest one comes to seeing it are the people who get involved in Peace Corps work or those people involved in in the the Dr. Martin Luther King's movement. Those who come into the neighborhoods and actually live in the community with people and try very hard to to meet the problems by living with the people. But that kind of a person who came gifted with education and money is not there because -- and this is one of the reasons why we're not getting the new directions as quickly as we might get them, I think. We do need gifted people.

Studs Terkel Yeah, well, the gifted people then will come from other sources, in other ways, we trust. It does among the young, by the young, speak of the, I speak of the young--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel There's a book that she always carried with her and suggested that everybody read--

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel You brought it with you, and it's Jane Addams book: "The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets." And Jessie Binford, I wonder if this could ever be reissued, because this is a book that Miss Binford has always mentioned and it's her -- it's one of Jane Addams, it's her great work, based upon her experiences. Macmillan published it in 1910, and I don't know whether it's been reissued or not, but it seems as if Macmillan has published it, perhaps a reissue might certainly be in order as a paperback would be fantastic.

Studs Terkel It ends and this is the -- that which you marked, or Jessie Binford marked?

Florence Scala She marked it, yes.

Studs Terkel June 1963, the last page of Jane Addams' book, which perhaps is, represents her credo and may I suggest Florence Scala's, too: "All of us forget," wrote Jane Addams, "All of us forget how early we are in the experiment of founding self-government in this trying climate of America. And that we are making the experiment in the most materialistic period of all history." Get this, this is written nineteen-nine.

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel "We're making the experiment in the most materialistic period of all history. Having as our court of last appeal against that materialism only the wonderful and inexplicable instinct for justice which resides in the hearts of men which is never so irresistible as when the heart is young. We may cultivate this most precious possession or we may disregard it. We may listen to the young voices rising clear above the roar of industrialism and the prudent counsels of commerce". Oh, baby [laughter].

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel "And the prudent counsels of commerce. We may become hypnotized by the sudden new emphasis placed upon wealth and power, and forget the supremacy of spiritual forces in men's affairs. It is as if we ignored a wistful, overconfident creature who walked through our city streets calling out, 'I am the spirit of youth. With me all things are possible.' We fail to understand what he wants or even to see his doings, although his acts are pregnant with meaning and we may either translate them into a sordid chronicle of petty vice, or turn them into a solemn school for civic righteousness." And Jane Addams' last paragraph: "We may either smother the divine fire of youth, or we may feed it. We may either stand stupidly staring as it sinks into a murky fire of crime and flares into the intermittent blaze of folly, or we may tend it into a lamp and flame with power to make clean and bright our dingy city streets." Well, somehow in reading this last paragraph of Jane Addams' work that Jessie Binford marked, written in nineteen-nine, you realize how much of a prophet Miss Addams was.

Florence Scala Mmm, yes. This book is really not outdated, Studs. I've heard people mention it several times as being a kind of a classic, because she was a prophet. I know she was. And one needs -- you have very little difficulty in translating the problems those young people then and today. And I I tell you, and I suppose it will be a never-ending quest, but you have, one has a very strong feeling, in the cities anyway, in the big cities, in the industrial areas of the cities, that not very much has changed. Not not very much. You know, there are a lot more agencies, and all kinds and all that. But this, this spirit that she's talking about, which must not be damaged, that James Bevel talks about, you know. That some of the young people in the slums are damaged beyond repair, now. This should never have been allowed to happen to the young--

Studs Terkel Of course, what's what's perhaps most depressing is with the vision that Jane Addams had and that Jessie Binford had, you speak of the 'hasn't changed much' since nineteen-nine, 1910 when Jane Addams wrote these words. If anything, in a sense, they've become the enemy, you know, the young.

Studs Terkel And more and more as though we -- just as Jane Addams is a prophet here speaking of the, what's that phrase? "The prudent counsels of commerce"--

Florence Scala Yes.

Studs Terkel "Hypnotized by the sudden new emphasis," this is nineteen-nine, I tell you, "sudden new emphasis placed upon wealth and power." That is saying, wait wait, don't don't rock the boat.

Florence Scala Right.

Studs Terkel Or, if that's it, let's put them away or whatever it might be. And thus we've had any, with the recent events, certainly recent events are part of it, this complete insensit- this towering insensitivity--

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel On the part of the establishment, no matter what agencies or how many--

Studs Terkel Have been created, you see. We come back, at [self?], perhaps in the time remaining, Florence, there's one personal incident I want to ask you about, about Hull House, the -- about you and Jessie. This one thing, you and Jessie Binford, Miss Jessie, there's one thing that, you said Jane Addams never had, and she never had, that sense of self-righteousness, that sense of moralizing.

Florence Scala No.

Studs Terkel Of condemning someone who may be different.

Florence Scala Never. That's, this is a thing that we we discovered with a kind of surprise ourselves, you know, we we tend to damn and be terribly angry especially in those days about the things that were happening and in the way they were happening. And we would confront Miss Binford with it, you know. And she always seemed to sort of take it without a great deal of surprise and did always really say that one ought to try at least to put oneself in that other person's position to try to understand without condemning.

Studs Terkel [Somehow?]

Florence Scala It's very rough to do sometimes.

Studs Terkel Yeah, and somehow as you say this, I can't help but think of editorials of our papers, you know--

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel Of recent events and--

Florence Scala This doesn't mean she didn't get mad, now, you know, she often got mad.

Studs Terkel No, I'm talking about the smugness--

Studs Terkel The monumental insensitivity, the, if I may use the phrase, the fat-headedness.

Florence Scala Yeah.

Studs Terkel The fat-head and the fat-around-the-spirit that made for these editorials.

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel If we, perhaps the last thing, Florence, your first meeting, we have about five minutes or so, to how this came about. You lost the battle, but you had seen, you as a young girl and around Hull House and around Harrison and Halsted, had seen Miss Binford many times.

Florence Scala Mhm.

Studs Terkel And then you met her.

Florence Scala Yes. Well, of course, when I saw her as a kid, Studs, she was in the JPA, in the Juvenile Protective Association. And I tell you, this woman, she didn't just walk, she had, she strode through the room. She had just a beautiful kind of a way of walking. And I used to see her mostly when she'd walk through the house to go to lunch, and she had some of her friends with her. And we were always kind of a little scared of her, you know, because we didn't have much to do with her in terms of program, you see, she was always involved in a lot of serious problems in the courts, in juvenile court. And we'd always know that Miss Binford was coming through to the house. And I knew her in just a very sort of casual way throughout the years. Knew her well enough to stop and talk, but had no real relationship with her. And when this thing was announced, about using the area for a campus, she was the only one of the old Hull House group, there were other residents living at Hull House besides herself who felt as we did, but she was the only one of that old group that decided that something was wrong and a stand had to be made. And when we had our first community meeting, she was there and we wanted to test her because we knew that something was wrong. Hull House had not called or cried out alarm, you see, and we wanted to test and we invited her up on the stage and she made a most eloquent plea for us all to be together and for us all to question this. And from that moment on we we became, from that very moment on, we became friends. And it, and we really went through a period of testing each other. You know, I really I had to measure up [laughter] in many ways, and we did. But I tell you once we did there was no need. It was as though it had gone on for all those years.

Studs Terkel Well, if I may say, I say out of this crucible, and a traumatic one it was and terrible, the destruction of an area and of a place -- out of it came a knowledge and a friendship of Jessie Binford and Florence Scala. And though Jessie Binford has now died and a young woman filled with life at the same time to spare, is Florence Scala around. So it seems there is never really, people such as Jessie Binford, Florence Scala, there are never really endings, only beginnings. Florence, thank you.