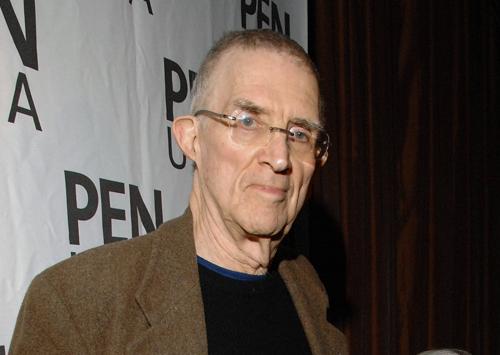

Dr. Bertram Carnow and Bob and Joan Ericksen discuss occupational illnesses and pollution

BROADCAST: Nov. 21, 1974 | DURATION: 00:53:32

Synopsis

Both Bob and Joan Ericksen ask why is a school being built not only by two highways but right next door to a paint factory. They contend that the paint fumes can't be good for anyone to breath. Instead of asking their patients where they work, Dr. Carnow believes more doctors need to ask, "What do you do?", to determine if they're working with any hazardous materials that may harm their health.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel My guests this morning are three colleagues of past programs. Dr. Bertram Carnow, who knows about as much about pollutive--pollutive what, pollutive ailments, challenges, and the aspect of quality of life as any doctor I know, or for that matter non-doctor, too. Dr. Bertram Carnow, professor of Public Health at University of Illinois and occupational ailments, too, is one of his interests among many. And with him two colleagues, Bob and Joan Ericksen, who work very unconventionally on their own. And the subject of interest of them is quality of life, that's all of us, and they're of the Sun Foundation, working with young people in open forums. The program in just a moment after this message. Where should we begin with Bob and Joan Erickson and Dr. Bertram Carnow? We continue where we left off. Last time talked about occupational hazards and pollutive ailments and our being buried in cement. "Quality of life" is a phrase that's general, but when I say quality of life to you and what's happening to it, Dr. Carnow, your first reaction?

Bertram Carnow Well, one of the things that was interesting to me, Studs, I just came back from the American Public Health Association meeting and was involved in a discussion about the whole problems of the urban poor and inner-city people and the theme of the meeting was health and the urban poor. And one of the things I noticed was this continued emphasis on, you know, the incredible problems that are still being faced. I heard people talking about lead problems which we've been trying to deal with for many years, and still keep coming [up? out?] with Black kids with lead poisoning and, you know, not only in this city. You know about El Paso, where we found that there are a bunch of kids with lead poisoning near a smelter and on the basis of the work we did down there, they have begun to look around the country, and now in Idaho they just found, they tested 179 kids living downwind from a smelter, and found 177 of them had lead poisoning. So here's a problem we talked about, it's still there, we talk about quality of life. Nothing seems to be moving. And the other thing was this tremendous concern, and a reasonable concern, with the rat problem. I remember when I interned at County, treating kids who'd come in with the ears bitten or the part of the nose bitten, or things like this, and this tremendous concern that parents have about their children. Well, the problem seems to have ameliorated somewhat, but there's still a lot of it going. But the other thing that got me was this feeling that the whole problem of air pollution was something that was kind of a suburban and dilettante problem. And it really isn't that at all. You know, air pollution affects everybody, but one of the things that we found in our study is that it affects poor people the most, because you see, what happens is that it represents a tremendous environmental stress, and the less that one is able to cope with an environmental stress the more the possibility of being overwhelmed, and because of the poor housing and overcrowding and inadequate medical care and frequent respiratory infections that are not being treated and so many other things, air pollutants just has a multiple effects on these people. And the other thing that people in cities really don't know is that they're being assaulted by a whole number of pollutants altogether, you know, the interlaced highways, the traffic, all of the pollutants from that. The fact that you have high concentrations of buildings and all the pollutants coming from the buildings, so that the impact of this on the poor is very great. And one of the things I'm hoping is that, you know, there isn't this attempt to separate one thing from another because they all parlay to destroy life, to intimidate, to frighten, to degrade, and to take away, you know, the kind of dignity that any society has to try to achieve for the human beings who live in it.

Joan Ericksen I think in, about a year ago in Chicago, they did a study which they found that there are more Black children that had lead poisoning than white children, and there was a radio announcement that was given saying that Black children were more susceptible to lead poisoning, and we had called and tried to talk to the people who had done the study and we had found that one factor that was really not considered was a factor of most of your very poor housing is located above expressways in high, dense areas--

Bertram Carnow Well, of course.

Joan Ericksen

Bob Ericksen And I think-- These are all in poor schools.

Joan Ericksen Right. And the schools, the playgrounds are all located near the expressways. Plus, I think you remember the case in Los Angeles, the young boy who died of lead poisoning about a year-and-a-half ago, and he didn't ingest lead. His house was above an expressway and he was just inhaling, didn't have a good system, he didn't have good livers and kidneys, and he couldn't filter out what he was taking in.

Bertram Carnow You see, one of the things that people don't know is that when you inhale lead, you absorb 30 or 50 percent of it, and it goes right into the main circulation. If you eat lead, you only take in five to 10 percent, but I think the point that you're making is very important. I think this is a fantastic rip-off. This was what they used to use with tuberculosis, that, you know, Black people are more susceptible tuberculosis, and, you know, it has no relationship to that tuberculosis is a disease of poverty. And any one group that where the standard of living goes up, that tuberculosis begins to go down. So that first it was the Blacks, as their standard of living went up and Puerto Ricans moved into New York, they were the ones that had all the tuberculosis.

Bob Ericksen Doesn't this get back to the problem we were just beginning on a few minutes ago of the idea that the whole issue of the doctor studying disease rather than focusing on health, that is, all the research is being done not on the optimum environment, the maximum kind of environment, the that portion of your life that promotes health. Instead, we as scientists or doctors or researchers deal, don't we really deal to a larger proportion with disease?

Bertram Carnow Well, except for people in preventive medicine. And this is why I moved from clinical medicine into the Department of Preventive Medicine in the medical school. The problem with physicians is that first, people don't come to them if they're well, generally. I remember when I was in practice people used to come in and apologize for a routine physical examination, and I'd tell them, "Don't apologize, important that you stay well." And, so, the doctors are harassed. But all of our training in medical school is related to disease. And you know, it's more than that. We see people with disease instead of talking about health. We're much more concerned about treatment than we are about prevention. You see? And also in medical school is that there's one other bad thing about it, is that we become organ-oriented. You know, you look at a gallbladder or a murmur. You don't look at a people. You know, this is a guy who's worried about his job, they're going to repossess his car, there isn't enough money, and everything else, and all you see is a murmur or a gallbladder, and I think that one of the things that we've been trying to push for is this total approach to these questions, to prevention, to health instead of to disease, and to thinking about people three-dimensionally as people with pain and suffering and families and concerns, because if you don't think about those things, you can't treat them adequately.

Joan Ericksen Is the young doctor who is going to medical school today being trained in nutrition, being trained in environment, examining the air quality of a person's home like we were talking about tuberculosis. Now, if you go to the Indian reservations and you see what type of fuel people are using in the interiors of their homes and the amount of respiratory diseases that are, you know, stemming in that area due to just the air they're breathing in the interior of their homes during the winter, is a young doctor being prepared to really look at the environment of his patient as much as he possibly can?

Bertram Carnow The answer, of course, is no.

Studs Terkel Interesting that Dr. Carnow is touching, and so is Joan and Bob Ericksen, that everything is related. This attempt to--it's funny how one thing leads to another, you speak of the doctor as a specialist, he's the gallbladder man and doesn't concern the person. All his, not only his body but the way he lives and also environment, considered something in which the elite are interested in and the poor need the jobs. You're saying all is one, right?

Bertram Carnow Well, sure. Just take, for example, you take the problem of the inner-city Black in relation to air pollution. A thing they say, "Well, we can't concern ourselves about that because we've got to worry about food and jobs." And certainly this is true, but you see, the job has a lot to do with it. If you take coke oven workers, now coke oven workers have ten times as much lung cancer as other people. Now most of those coke oven workers are Black because it's the dirtiest job, it's the heaviest job, and most of them have these jobs. If you take that and if you take urban air, because we found in studies that we did that people who are exposed to urban air have a lot more lung cancer because of that. And you parlay these things, you begin to realize why the incidence of lung cancer is going up so much particularly in these groups, and why a lot of Black males just don't live long enough to collect Social Security, so that, you know, the whole thing comes into play in this. You take, for example, the kind of heating that they're on in many of these homes, space heaters are used. Now, these space heaters, first of all, give off a lot of noxious gases, carbon monoxide nitrogen gases, and if they're not well-vented, and many times they're not, they can be a serious problem. The other problem is that in a lot of poor areas where they turn the heat off at eight or nine o'clock, people turn on a gas range, or they turn on the oven. Well, you know, those things are not vented it all. And, so, you get the production of a lot of irritant and noxious gases. Well, all of this, and they're all conditions of being poor in an industrial society, all of these add to each other to make each one of them a terrible burden.

Joan Ericksen Could you tell us what would, what might be some of the effects of these fumes, besides, you know, being poisonous, what about anemia? What about--what would be some of the side effects--

Bertram Carnow Well, you know, carbon monoxide will produce at first a lot of headaches, and ultimately, and fatigue. And ultimately if you have enough carbon monoxide, then you become unconscious, you get brain damage, and you can die. Some of these irritant gases cause an irritation of the lung, and, so, that when people are then exposed, say, to influenza which is going to come along this month, and if in addition to that they're exposed to a lot more air pollution which is going to increase in November, it always does, all of these parlay to make people more sick, so you have more bronchitis, more pneumonias, more respiratory--

Studs Terkel I was thinking of something, by the way, Dr. Carnow, a while back, Joan was saying, you know, heard that Black people are more susceptible to tuberculosis than white, and you exploded that, we hear a lot about Black people being susceptible to sickle cell anemia, would that be related, too, to conditions and circumstance?

Bertram Carnow No, that's different. That's a genetic defect, that's something that's inborn in the sense that this is something you get from your parents, and there's a great--

Joan Ericksen Like, how far back? How back in a person--

Bertram Carnow Well, you see, we don't know a lot about this. One of the things that was told to us in medical school, and I don't know how firm the data are, is that people with sickle cell anemia in Africa who are protected because the malaria mosquito cannot invade the blood of somebody with sickle cell anemia. So that, while other people may have died from malaria, people with sickle cell anemia were protected, so it was a protective gene. In this society, where there is no malaria, then it can become a destructive gene, you see.

Joan Ericksen Could people in Africa who have sickle cell anemia function properly and live long lives, or was it something that was debilitating as it here?

Bertram Carnow Well, no, it was, it still might shorten their lives, but it wouldn't shorten it as much as if they had serious malaria which was a scourge, you know, for many years.

Studs Terkel Back to this theme, that Dr. Carnow was talking about, everything being related and how specialization will kill us all. You mentioned about coke workers, many of whom are Black, getting the illness, a number of books come out now about workers generally, Black and white. Rachel Scott's new book, "Muscle and Blood", [and a number of?] others. The number of industrial ailments are overwhelming, you know. Charles Dickens is alive and well and living in the United States today, and this applies to white workers as well as Black, in asbestos mines of course, many of the new chemical plants, as well as the mines, but of the new products and the incredible number of the diseases and accidents is just astonishing.

Bob Ericksen But, excuse me, but different from Dickens, in other words, in terms of our kind of viewpoint of the whole problem. We have the information.

Bob Ericksen

Bertram Carnow the information. In Dickens' time, it was sort of un-- Well, no, we have some information. You know, it was interesting, Studs, you had this--you say there's so much more occupational disease, those diseases were always there. The problem is that they weren't being reported and nobody knew about them, and one of the other things about these diseases is that as people live longer, they're living long enough to get these diseases. You see, workers in asbestos plants used to have massive exposure and he died from asbestosis, which is a scarring disease, and he wouldn't live long enough to get the lung cancer from the asbestos. Now we're seeing the lung cancer from the asbestos. So as certain conditions get better, the diseases that take longer to develop are beginning to emerge and the things that you say are true and, you know, it's incredible to me, the shortsightedness of some people. You take something like this vinyl chloride business. Now, vinyl chloride is a very important material used in plastics, it's used in hundreds and hundreds of industries. Worldwide, there are now 57 billion dollars' worth of industrial production dependent on vinyl chloride, and now suddenly we find out that this thing is extraordinarily toxic and it causes cancer of the liver. Now, how do you deal with that kind of a question? Industry says, "If you take away vinyl chloride, you know, you're going to destroy industry." On the other hand, you can't destroy workers. Well, and the answer to that, obviously, is not to get yourself in this kind of a box. And one of the things that we have to begin to do is make an assessment of a number of things. First, when we introduce something new into this society, we should decide is it really something that's important. Is it something that's necessary, and that's something that we don't do. The only question that we think about now is it something that will reap a return, a financial reward. Well, if vinyl chloride had been looked at really carefully, it never would have been introduced, so it wouldn't be the serious problem it is now, you see. And there are so many other areas and some of them are so frightening the business now with textile workers. I don't know if you know about this. But we have a new process. You know, we have anti-creasing agents so that pants don't crease, and we also have waterproofing agents, and they're very useful. But what happens is that, in order to do this, you use a chemical called formaldehyde, which is a very common chemical, it's used in embalming and things like that. We find out now that formaldehyde in the presence of any kind of chlorinated compound, the compound you obtain in the chlorine in the air, and there's a lot of that in textile places, in laboratories, and so on. These combine together to form a compound called bis(chloromethyl)ether, which is deadly in that it causes lung cancer. So here you'll have another potentially explosive problem, you know, based on new materials, new compounds, and we really don't know how useful those things are. And again, I think that, again we get back to quality of life. We have to begin to assess how good is what we are using because everything that we put in society today, a lot of these new chemicals, we've had no life experience with, you know, evolutionary-wise we have not learned to adapt to them. And if these things are toxic, they're going to give us a lot of trouble.

Joan Ericksen Is the medical profession also using medications that are toxic and that are causing a great deal of damage to people?

Bertram Carnow Well, there, you see, there's a much more quality control, although we still get into trouble. There's a drug, for example, reserpine, that's been used for many, many years, and it's a valuable drug in the treatment of high blood pressure. Everybody has used it. Well now, there seems to be, there is a study that's emerged which suggests that women on reserpine have more breast cancer. Now, we don't know if the relationship is to reserpine or to the disease that the reserpine was treating, the hypertension, so we really don't know. But there seems to be a relationship. But again, you see, if you monitor people, if you introduce something new that's needed, and then you monitor to see that it doesn't do harm, or whether it's doing harm, you can withdraw it if it does. But the first evaluation you have to make is, how valuable is it.

Studs Terkel You know, isn't Dr. Carnow, Bert Carnow, raising the key question, how valuable are some of the new phenomena thanks to technology. Barry Commoner raised this very point, that technology has failed, but that is used very well indeed, but toward what end? George Wald, the Nobel laureate, raising what science is finding, but toward what end? And of course, both of these men introduced the word "prophets." You know, and how it--profits may work for the few, will destroy the great many, including the few eventually. Isn't this what it's about, really, technology toward what end? Not that technology is, per se, bad.

Bertram Carnow There's no question. Yet I think, you know, one of the things that concerns me, too, about young people is this rejection of technology. This feeling like, you know, they've been ripped off, they've been poisoned, they've been harassed. And this is not the kind of world that they want. And I think we have to recognize that the cave was a very uncomfortable place.

Studs Terkel And indoor plumbing is good.

Bertram Carnow And indoor plumbing is really good. And I think that the big question is, who is the master and who is the slave? Is the technology the master and is man serving it, or is technology the slave and is it serving us?

Joan Ericksen Do you really mean that? That indoor plumbing is good?

Bertram Carnow Of course it's good, because if you have 200 million people, and you're using outdoor plumbing, you know, you're going to pollute everything, you're going to have typhoid epidemics, you're going to kill everybody. So that, sure, it's not only good, it's essential.

Joan Ericksen Possibly if it didn't use water and it could be handled in a different way possibly would be much better. I mean, the same, you could take technology and develop a waterless toilet so that the water that is used would, could be used--

Bertram Carnow But again, you're still using technology.

Joan Ericksen Right, of course.

Bertram Carnow Now, you're using it in the right, in a--

Bertram Carnow In a better way, yeah. You know, you can recycle stuff, and--

Joan Ericksen Because I remember that there were so many deaths per year of people related to water contaminated by using water for this type of, you know, function using it to get rid of our waste and it could possibly by not using water eliminate some of the disease that is caused by this kind of carrier.

Bertram Carnow This is possible, except water is the best way to flush away waste, you see, and it's--

Joan Ericksen Air

Studs Terkel sounds good. Something interesting here, Bob and Joan Ericksen and Dr. Carnow, and I think I'd be close with Dr. Carnow, I'm just guessing. I think as soon as I said indoor plumbing is good, I know you raised your eyebrows, because I know that, see Joan and Bob Ericksen work a lot, too, in the countryside. You know, and you work to preserve whatever there is of nature that is good, as Dr. Carnow, but I do think that maybe, do you have a slight, don't you two, by the way, have a slight feeling toward technology anti, stronger than say, Bert Carnow and me.

Bob Ericksen No, I don't believe it's anti. I think it's the way that that technology--

Bob Ericksen And, again, we're parallel with Bert on this. The way it's been utilized and the way it's been handled, and for instance, you know, in our experience in living in the countryside and studying with people who and working with people who are very, very rural where there might be an Indian or someone living, you know, on a farm in the corn belt, in many cases if you take that farmer and his life pattern, that is, how he utilizes his resources, what he does with his day, and if you put him in a city with the same capacity to utilize resources and utilize them in the same way, he'd be devastating. I think in many cases the individual living in a city relying on technology as he does really could be viewed as being much more economical than the rural person. The rural person in many cases is a real waster. Maybe technology is not really the base issue, it's not that, I don't think it's that Joan and I are anti.

Joan Ericksen I think it's learning to understand it, to be able to see it, to see how it works, the importance of understanding to the individual to learn how technology affects his life and to be in control of it, most importantly. To be in control of it. This is what you're talking about, this is what we're talking about, to be in control of it, to be on top of it, to understand it, before it has an effect that is not desirable.

Bob Ericksen Most people are overwhelmed by a new product.

Bertram Carnow Well, you see, this relates to everything, you know, everything relates to everything. If you look at the energy question. This is the whole crux of the energy question. You know, aluminum foil. It takes 40 million BTUs to make a ton of this material.

Bertram Carnow Well, British thermal units, it's an energy unit, that's a lot of energy, 40 million BTUs, you can heat a lot of houses for a long time or create electricity for a lot of people for a long time. Well, you know, using aluminum foil, now aluminum foil may be very important for certain things, but it's not important as a substitute for wax paper. It's not biodegradable, it's not anything. Well, you know, this is a waste. But with a whole energy thing, and we just finished a study for the fourth, and the whole energy thing, you have to come to the conclusion that no matter what you do about the energy business, and no matter what kind of energy you use, nuclear, coal, it doesn't make any difference. You're going to reach a point and it's going to be in the next 30 or 40 years at the outside, where we're going to have to come to an energy equilibrium. It's going to have to be a society that's based on an energy equilibrium, and that means that for every BTU or every megawatt that you put in, we use megawatts now, of energy you put into a society for something which is a useful function, you're going to have to take a megawatt out for something which is no longer as useful, because in a finite system you can't have infinite growth. It's mathematically impossible. And this is what's happening with energy. You know, this thing is doubling, and the doubling time is getting shorter, and the slope is getting steeper, and we're going to reach a point where you'll overload the atmosphere and you use up all your resources, and then there will be chaos. Then there will really be chaos.

Joan Ericksen I think our objection or maybe why you caught my eyebrow raising about the toilet system, the fact that we're using a great deal of our water supplies for waste and I think in industry we have seen some really beautiful bodies of water that support life systems as well as our own that have been really misused. And it's not the idea of using a toilet, it's the idea, can we design, this is what we wanted to talk to you about, the designer, his responsibility to design a facility for a human being to excrete his waste and have it return in some way to the soil. This is a chain that Dr. Commoner talks about, putting back as much as you take out and--

Studs Terkel What the Chinese do.

Joan Ericksen Right. For that matter, in our work in the rural areas, we find that when we come into the city the problems that people are talking about in the city are really there. Recently, a very close person in our family was poisoned possibly by chemicals used in these farming apparatus and there are many people on the farm today that are being affected by chemicals and air pollutants. We, you know--

Bob Ericksen The separation between the city

Joan Ericksen

Bertram Carnow and technology-- It's not that different. If we raise another question, if you're asking whether or not we can structure an environment where humans can live in dignity and live out their lives pleasurably, absolutely. You know, that could--that's all been worked out.

Studs Terkel You know, I think that's a good spot right there. How, we come to the "how" in a moment, there's never really been, never really is taken seriously by those who, the power boys who run our society. So we'll come back in a moment to how to make this a sane society, sane really, in a moment with Dr. Bertram Carnow and Bob and Joan Ericksen and we'll return after this message. Resuming the conversation with Dr. Bertram Carnow and Bob and Joan Ericksen about quality of life as a general theme. Also, how technology is misused, you know, for Dr. Carnow points out, tinfoil. You know, Barry Commoner, I think, also, you yourself were--I think the new machines now, too, they're being so--the Bendix machine can't handle soap any more. It's for detergents, you see. They're products that make a lot of money. And the new machines are designed to handle only the products made--not the old one that may have been better and less harmful. That's part of it, too, isn't it?

Bob Ericksen That doesn't mean turning the clock back a hundred years. I mean, soap doesn't really relate to, you know--

Joan Ericksen We have to go forward.

Joan Ericksen You think about the role of the designer in our society or the inventor. This is really where we--

Bob Ericksen Or the industrial designer.

Joan Ericksen Yes. And how much he has understanding of biochemistry, has understanding of his own body, or--

Bertram Carnow Well, he has an understanding of it, but he doesn't have any understanding of really what people need. It's more of thinking about what will attract people, what people might want rather than what people need. And I think that the needs are the critical things. It's interesting that the, you know, the car with the stolid front has now become the status symbol rather than the big chrome-plated thing. And how all of the American manufacturers now, every car now is beginning to look like a Mercedes. You know, it's going back, I suppose, in certain areas to basics. I think that when you look at the buildings. You know, we have an architectural giant, our Circle Campus the University of Illinois, well, there's one building there that is incredible. In order to take an elevator up to the top you have to walk in and out--

Studs Terkel You mean incredibly bad, you

Bertram Carnow mean. Well, incredibly bad. You know, it was designed by a man in his Cubist period I think, and you can't find any of the rooms, and the rooms are all the wrong size and the wrong shape. And as far as I'm concerned, you know, this really is what that part of the thing is about. There is--you know, for example, you build buildings without windows. And that's what they're doing now. You become totally dependent for your light and your heat and your cooling on machines. I worked in a building like that. I had a practice in the building like that. And when the air conditioner was out, everybody would die because there was no way you could go.

Studs Terkel You're hitting on my pet grievances on the road recently. This applies, this is all related to the certain--the lack of control we as humans have over the manner in which something that is voguish, nothing wrong with air conditioning, but air conditioning in the motel, for example, the window cannot be opened.

Bertram Carnow That's terrible.

Studs Terkel You're in the bus and no one complains. I sort of speak loudly in bus and I try to find a foil, you know, say, so they won't think I'm nuts, you know. "Hey, can we open the window?" The window can't be opened. Everybody's perspiring, and in the old days you could open a window, you know? You could open the window in the hotel, you can't anymore. And isn't this part of it, too, as well as the Muzak coming, [fed?] at you in the elevator--

Studs Terkel As you go visit the dentist or doctor? Or the plane landing, they get Mantovani. Who asked for Mantovani as the plane lands?

Bertram Carnow Well, and that's it, you see what--here's the way you parlay it, you see. You take a natural environment and the good smells of the open land, maybe, you know, you mess them up with everything. You see? Fertilizer, pesticides, smoke, pollutants. Then you say, "Okay, this environment is terrible to breathe. We'll give you a nice artificial environment to breathe," and then you structure that so that it requires infinitely more energy, which then messes up the outside environment even worse, and you keep crawling into a deeper and deeper hole, and then if your machine breaks down, then you're totally lost.

Studs Terkel I must, there's one quick story, and this opens it all up, it's about progress. So I'm in this cab, it's a privately-owned cab, and it's absolutely stifling. I can't breathe. And the [carrier says it's?] his car, he says, "We're air-conditioned, you fool." I says, "What do you mean, air conditioned? But I can't"--"Open the window!" "I can't open the window. I got"--You know how much this air conditioner cost me?" I says, but--and then suddenly he says, "Oh, you're one of those guys, you're against progress. Aren't you for progress?" So there you have it. What is progress? You come back again to technology and use of it, don't you?

Bertram Carnow Sure do. And every place you look it's there. You remember last time we talked about the hazards in the arts and crafts and I've gotten involved in that, I'm finishing a book on this now and one of the things I realized is that there are millions and millions of people exposed. You take photography. Now, how many people are working, you know, in developing their own pictures? Well, everybody picks out a little closet and if there's any light or any ventilation at all, you block that off, see, because you've got to have dark in there and there you are, exposed to a bunch of chemicals which can irritate the lungs, can cause all kinds of problems. And, so, that it even intrudes into these areas. You know, we--There was a time where people just used watercolors, and you know, these are very benign.

Bob Ericksen There was a time where you could develop your wet plate process photographs in the field.

Bertram Carnow Yeah, sure, sure. And now the chemicals are very complex and in many cases very irritating. But the thing is that we go from simple things to complicated things and I'm not sure that what we're doing is meaningful. Now, it is very exciting to see some of the newer acrylics, for example, in the arts as seen in some of the newer media that people work with. The only thing is that these people are not aware of what they're dealing with. So again, it's a question of knowing the technology, knowing what it can do for you, and what it can do against you, and then controlling those factors which are bad factors. I think that's the thing and it doesn't matter what you go into. It's the farmer, it's the artist, it's the worker, it's everybody.

Joan Ericksen I think as you travel, too, you really realize that you can't get away from these things. You go to the washroom and you find they have some kind of a fumigator in the washroom that is killing germs every, so many minutes and you have a lot of the grocery stores are now spraying things continually. So you're breathing that. There's very few places that you can go where you can get an environment in which something isn't being done to docu--you know, sort of change the smell. We had some interesting studies that we did, we were in pursuit of some buffalo chips that we were doing some research and we spent a lot of time in zoos photographing buffaloes and we had to eventually go to the bison range because the buffalo chips, of course, in the zoo are very hard and the buffaloes are usually constipated and we had to go out to the bison range and to get a beautiful very nice-smelling chip. And we began to realize that how much the environment can really change. We're back again to the toilet, I guess, but the smell of animals has changed also. The farmers are telling us that since the new feeds that they're giving the animals, that the animals didn't smell before. Now you can't get anywhere within ten feet of a barnyard without having it really knock you over. And, so, there are chemicals also being introduced in through our food chain that make us smell differently and act differently and change differently, and we wanted to talk to you a little bit about that Studs, too.

Studs Terkel Animals and additives, animals then are also taking food additives as well.

Joan Ericksen And their behavior is changing, too. The farmers tell us that the animals are more aggressive. They seem to have changed, they're killing their young. The--it's interesting when you see animals, you know, cooped up, being force-fed in a stockyard and see their reactions in comparison to people on the street and you go to Montana and you see people who have a great distance between one another and very relaxed, they have time to talk to you. The smile on their faces is, you know, is full. I think there's a lot to learn about what we're doing, you know, as far as stress and the physical intake of people and animals.

Bob Ericksen As we change this conversation from people maybe to animals, too, or begin to include the animals, it's interesting to note that one of the large feedlots that went to replace the Chicago stockyards located near Joliet is in fact downwind from the industrial plants in Joliet. So in other words, the animals are not just being moved to a clean environment, they're being put, really, right back into the industrial park. So the same forces that are affecting, you know, poor people in the cities are really right there in the backyards of the animal.

Joan Ericksen When we were talking about the highway and about the effects of carbon monoxide. Can we talk about behavior, about what pollutants do to people and their behavior?

Bertram Carnow Oh, sure, well, you know, there's not very much documentation of this, but there's some, now certainly with some of them, like lead, we know. One of the reasons that they didn't find the kids in El Paso is because they didn't look at what they had to look at. These kids developed increased irritability, or not they would be very lethargic. These are two hallmarks of lead poisoning. Now, we don't know whether irritability of people in big cities relates to some of these things. Certainly overcrowding does that. You know, rat colonies that are bred when at a certain point in overcrowding begin to develop strong asocial behavior. They become combative, they become isolated from each other and alienated, they begin to show deviant behavior in all regards, they're going deviant sexual behavior. So that this is not unusual. Now one area where the whole question of psychosocial stress has not been emphasized, then we're developing a program at the School of Public Health, Dr. Ben Liebovitz has been heading up our program, is looking at psychosocial stressors in the workplace, because the whole question of what alienation from the job, what heat and pressure and--

Studs Terkel Noise.

Bertram Carnow Noise and chemicals and fatigue and a lack of pride in production, what all of these doing to the worker. And I'm sure that some of the problems of alcoholism and absenteeism and drugs and so--

Studs Terkel Note about the battered child as well.

Bertram Carnow Oh, sure, sure. You know, it's a problem. Somebody's got to pay for the frustrations that the people and the kind of things that they can subjected to. But the thing that's most encouraging to me is that there have been now a number of strikes which have related only to the conditions of work, and not at all to money. You know, up to now, for a guy to go on strike and jeopardize his job and have no income, it had to be on a real hard pay question, but I think that the workers more and more are beginning to recognize the impact of the environment on their health so that in one big steel operation the coke oven workers just walked out, because they didn't want to get lung cancer.

Studs Terkel Or you have the absenteeism of the auto workers on a Monday or Friday, the [unintelligible] had nothing to do with wages and hours, yeah.

Bertram Carnow That's how well the Ford strike, was a strike that was purely over noise and heat. Those were the two big factors.

Bob Ericksen Your experience, Studs, with the Vega workers relative to their--

Studs Terkel In Lordstown, Ohio, specifically that, yeah, more and more as Doc Carnow says, that's--and, so, we're talking about, again we come back to quality of life, it's felt and expressed, the want, the need for it in many different ways.

Bob Ericksen But as we began, we were talking about the issues the environment being somewhat compartmentalized and the forces against environmental degradation being really waged from a certain segment of our population. And, yet, here's a man in the Vega plant who's really fighting in an issue of environment. He's obviously a blue-collar worker, but he's on all levels--

Studs Terkel It's interesting, this, [unintelligible] there are very young workers there, and what's happened at first in many of the auto plants the old workers who are Depression survivors were wondering why these young guys and women go out on strike, when it doesn't concern wages and hours and now they begin to see how these young people are right after all. And also the lack of meaning to the work. But you know, we gotta drop that other shoe. Remember, earlier asked Dr. Carnow, you asked him, Joan, about what to do. Can there be a sane society? Can there be an environment that is pro-human rather than anti? And it comes back to you and public health and--

Bertram Carnow Oh, sure. You know, there have been groups, architects, engineers, people in public health who have looked at a lot of these questions. Whenever I talk to engineers I talk to them as colleagues and fellow health workers and that always startles them, because they don't think of themselves as health professionals, and I point out that they have an extraordinary responsibility, that when they build something they can't think only about the cost about the tensile strength of the materials. But they have to think about what this is going to do to the people that they constructing it for. Now we can, we have defined what the optimum city is. It's a city of approximately a quarter million people, because it's the kind of thing where you can regulate the water and the sewage and the air pollutants in terms of traffic density and so on. How big such a city should be, the amount of green space it should contain, the distance between it and a similar city. And there's no reason in the world why we can't build cities like that and then have fast, high-speed public transportation highways between such cities and so on. That you would give people living space, you would give them breathing space, you wouldn't have the incredible problems that we're having with overloading sewage plants, overloading the air, overloading all of the environmental sources. You see, you talk about using a different kind of sewage system and so on, nature has an incredible ability to recover and disseminate these materials. But if you overload, you see, if you put sewage into a stream, a clean stream, one mile downstream it's already processed by the bacteria. If you remove the oxygen from that water and you put sewage in and if there's no oxygen there, it will never be processed. So the whole idea is not to stop that kind of a thing but to create the conditions where you're working with nature, you know, in some kind of symbiotic relationship. But we don't do that at all. You know, if you look at housing around Chicago it looks like a cancer from the air. You see, pseudopods almost like a cancerous cell because there was no rhyme or reason for the way in which it grew. It grew because you could get a farm for 200 dollars an acre and build on it. And, so, what they did was they bought land that sat in the floodplains and now you have houses that have swimming pools in them all the time, every time it rains, and there's no way to do anything about that because you can't build on a flood plain, you see. And I think that those kind of controls--now people say that, you know, oh, this takes away our freedom. But, again, I think that freedom is the recognition of necessity. I think that no matter how you slice it when you get this crowded you've got to begin to move in these directions.

Bob Ericksen But I think the technologist and the designer and as you speak as you said to industrial designers or architects and call them, you know, fellow health workers. I don't think that's really so surprising because, for instance, in a city like Seattle, where I came from, the large body of water, the major lake in that city, Lake Washington, was incredibly polluted. I grew up as it grew more and more cloudy, and you could for instance see about eight inches below the surface. They cleaned that up, and it was not the environmentalists who cleaned it up. They got the public officials to--

Studs Terkel The environmentalists.

Bob Ericksen Yeah. The people who cleaned it up were the technologists, the men who designed the large sewage disposal system that in effect turned all of that sewage back out and into the proper disposal places.

Studs Terkel But these technologists did it because of pressure.

Bob Ericksen Exactly right. Exactly. The pressure they--the public--

Joan Ericksen If there's a need for it, if people want it bad enough, it'll be done.

Studs Terkel When you say people want it bad enough, there's a question I'm sure Bert Carnow would say about this, too, a question of how much they're aware of it, how much is kept from them, how much news is distorted, how much advertising is done on TV--

Bob Ericksen The mythology.

Joan Ericksen Well, this is the

Bertram Carnow mythology of understanding-- Sure, if you tell people, you know, well, if we don't use this toxic material you're going to lose jobs, which is, of course, nonsense, workers have been intimidated by this for years. You know, if we have to put in this control, we're going to have to close down a plant. Well, that's a lot of malarkey because when you begin to look at that, you find out it really doesn't cost that much. You know, a lot of it is just hygiene. A lot of the kids from these smelters are poisoned just by stuff that blows out from the plant because they don't take and cover up the damn piles that are sitting outside: the slag heaps and so on, and, so, the stuff blows off there. So it's just a question of minimum hygiene, it has nothing to do with fancy technology and so on.

Studs Terkel Come back to myth, this very point. Earlier, you remember Dr. Carnow how the ozone matter affects all of us, not just elitists and the poor people, this has nothing to do with me. This very point of plants, big companies threatening to close. There's one quite enlightened union in Colorado, the chemical workers union, and they challenged, and the people who work in this town, it's a Pennsylvania town I believe, says, what are we going to do, our jobs' going to be out, the company's going to close, and the oil workers are, we gotta, we're with you, and we're with the town, the company's not going to close because they're making a good profit. It's not going to cost--[unintelligible] They're not going to just give up all that profit and they called the bluff, now the improvements were--the anti-pollutive machines or whatever were put in, there was some expense, the company's there and the town is relatively cleaned up and the jobs, not one job was lost. This particular cutting off. Again we come to Madison Avenue and, again, we come to advertising, again we come to the tremendous public relations job done by the few who separate the many.

Bertram Carnow I get back to my favorite subject, the aerosols. This, to me, is the biggest rip-off in this society. People are being charged for a can full of stuff they can't see, and it contains half of what it should contain. They're exposed to materials which may be very toxic in aerosol form. You know, aerosols make these materials which normally don't get into the body in a millionth of an inch in diameter particles and these get way down into the lung, get right into the blood. So you have all of these materials, toxic materials getting into the blood that never got in before. And in addition to that, the propellant. Now the propellant itself is usually Freon or something like that. Well, we find out two things now: one, that this Freon can cause irritation of the heart muscle and can be very dangerous to people who are breathing it in. But a scientist recently showed that this Freon is getting up into the upper atmosphere and may cause tremendous problems. And you're talking again about millions of pounds of a material which is stable being produced and being shoved into our society. And if that isn't enough with the aerosols, the propellant and the material itself, some of the aerosols, particularly some of the hairsprays, were using vinyl chloride as a solvent, and the vinyl chloride causes cancer of the liver. So here you have a product which is totally unnecessary, in which every aspect of it is bad. It's expensive, it's dangerous, it's just bad, and it's something that we've been sold a bill of goods on.

Studs Terkel You know, we still have a few moments here, about 10 minutes or so I think, and I think what we're doing here, Bertram Carnow and Bob and Joan Ericksen, are just touching on familiar and non-familiar or semi-familiar aspects of our society. We're coming to the question of how to alter it so that we can be sane and healthy. Come back to national health and medical care, too.

Bertram Carnow Well, it has to be controlled. You see, the FDA, for example, is not providing adequate control. You know, a lot of the cereals that the kids are eating, you know, are non-nutritive cereals and the amount of nutrition in them is very, very small. You know, the only thing that's important is the milk, but, you know, the FDA hasn't really taken a strong position on this. In terms of workers' health, OSHA, you know, has 500 inspectors, they need 20,000 inspectors. They've inspected 7000 plants, they're going to have to inspect millions. You know, it would take them 500 years or 5000 years to inspect all the plants. So there's no commitment. So in terms of quality of life in the workplace, quality of life in the environment generally, community environment, the quality of life of people generally, the facts are known, the technology is there, all the will of the people is there, people want this. Now what we have to do is we have to make sure that those people who represent us, because ultimately it's a political decision, those people who represent us begin to move in the directions that we really want them to move.

Studs Terkel You know, didn't--Bob and Joan, didn't Dr. Carnow just now say it? The word was bound to come up: politics. And one of the horrors of the day at this moment is the cynicism of a great many people to despair, they'll take no part because of the deception high up and, of course, this is a horrible danger and the various exposes and marvelous ones have come through as Doc Carnow says, you know, the facts are known. The agencies are not enforcing it in the plants and in the housing they're not enforcing it at all. There's a silence among the company doctors, of course, your colleagues among company doctors are incredible.

Bertram Carnow Not so much now. There was a decision in a California court where a physician saw a man in a plant who had asbestosis, didn't say anything to the man, and on the stand, on the witness stand claimed that he didn't say anything because the guy already had the disease and it wouldn't have helped him and, so, he reported it to the company and that was enough. But the man said that if he had known he had asbestosis he would have left the plant. And the jury awarded him some $400,000, so then, I think that physicians who have an ethical responsibility to speak out when they see disease are now going to be a lot more cautious about not doing so.

Studs Terkel I hope you're right. That's one case, again I come back to the recent books on the subject. Very, very--

Bertram Carnow Mulder's book on the asbestos is a shameful--

Studs Terkel That one. Rachel Scott's book, Jeanne Stellman's book, a new book by a guy about asbestosis, too, asbestos and more and more of this coming out and still this tremendous conspiracy--

Bertram Carnow Right. And you see the role of everybody in this, in the asbestos thing it was the industry, it was the physician, the plant physician. It was unfortunately the government agency which played a shameful role in this and in that instance and I think that it requires that kind of thing if you had, if there had been one honest group in that situation that couldn't have happened, the thing would have stopped. These only work if you have a whole circle of people. See, the safeguards are there, but they break down when they're not enforced.

Bob Ericksen Or when they're silenced.

Studs Terkel they're silenced. Let's go back to Bob Ericksen's point earlier talking about Seattle and that water and that river it wasn't the engineers alone who did it, the technicians who did it. There was tremendous pressure. We come back again, don't we, to politics and the engagement of political life.

Joan Ericksen I think it also has to do with the method. When Bob and I have interviewed many, many people about this very subject that Dr. Carnow is talking about, a lot of people say, "Well, the government is watching out for us," or "They wouldn't allow additives to be put in food that are dangerous to children," or "These kind of things couldn't happen. There's someone looking out for us." The myth is that there really is somebody looking out for us, taking care of us. Where now there are more and more articles being written, the research that you've done, Dr. Carnow, I think your book, Studs, really gives people a lot of information.

Bob Ericksen It gives them hope, too.

Joan Ericksen It gives them hope.

Bob Ericksen The realization that there is a way out.

Joan Ericksen And more and more people are taking it on themselves to evaluate their own life, their own lifestyle, the ingredients that goes into their environment, and reading as much as they can. I think this is one of the things we can suggest to people is to not, you know, you know how slow things are, and how if we're going to wait for the politician to pick up the bandwagon, he will have to, right. But we have to be educated ourselves. We have to be on our toes as individuals. We have to really be in control of our own body, our own destiny, and to think that someone is watching out for us is really a mistake. And many people are really heartbroken when they find out, "How could this man let me be exposed to this chemical when he knows that it can cause liver or lung cancer?" which is in all cases just about, you know, terminal.

Bertram Carnow Oh, but what you're talking about then are levels of awareness and--

Joan Ericksen Awareness.

Bertram Carnow They think that they have to be based on a number of things. The first thing we need are some of the scientific evidences and we have a lot of those. The second thing is, I think, to really understand what the socioeconomic consequences are because they're not nearly as severe and they don't have to be as severe as people are led to believe and then, the third thing is to make people understand that implementation of all of these things has to be on a political level. I can generate all of the data on how bad pollutants are, which pollutants are bad and everything else. But unless a legislature passes a law or unless that law after it's passed is enforced, you know, and you monitor things in the air and you have inspectors to enforce and you have courts that will enforce, unless you do that, all of the scientific data and everything else is meaningless. So what we're talking about again is that the quality of life has to be based on recognition by people of what their needs are and what the rip-offs are, and then I think we'll move forward. I think that's really the answer.

Joan Ericksen Yeah, but probably one of most important thing is that a person like for--in your case you speak very clearly, you give a very clear language, you do not use words that really befuddle people. If the people that are working in the sciences, the people who are tabulating this environmental information could explain it to people in ways that they could understand, this is where we have to do our greatest amount of work. This is why Studs' books are very popular and very important to people, because they can read it, they can feel it, they can understand it and get information that's valuable and real. Now we have to take the language that the scientist is using and it has to be made clear.

Bertram Carnow It has to be translated. Well, if they all came from Brooklyn, it'd be no problem, see I don't know how to talk, I don't know how to talk scientific talk, so I talk people talk. That's--

Studs Terkel One last, one last go round, start, last go round, Bob Ericksen, just anything related to what we're talking about.

Bob Ericksen I think that the most important thing is for people to realize that, really, nobody is small within the system, that the whole interconnection that we've been dealing with in part and piece by piece today. But the most important thing is to just to look at that one person living in that one house, you know, whether he's by himself or in his family and that he's the individual that carries his whole destiny with him and he can or cannot be informed. He may or may not wish to put his fate, his life, in someone else's hands but to take it on his own is really--that's the incredible balancing act that we all have to begin to maintain.

Joan Ericksen The information is there. I think that the news media, the magazines are doing a job that some of the publications that are putting across this information are not very well-known. But I think that people can really, you know, be on their own toes and ask questions, ask questions of doctors, insist that, you know, a doctor understand their physical background and their environment when they go in when they're having physical problems and to search for ways to really feel good.

Bertram Carnow Well, you know, sometimes I have a déjà vu that we've been down this road before, but I think that while it's true and many things we have reiterated, I think that there's more hope now because I think that we are beginning to pull them together, we're beginning to tie them together. We're beginning to recognize that jobs, nutrition, work, environment, that all of these relate to ways in which we can begin to develop a life for people which is more than just going to work, going to bed and getting up and going to work again and dying at 62 so you never collect your Social Security, which is what is happening to a lot of Black male workers. I think that we are beginning to pull it together. And I think that while people may not be as noisy about the environment, every time somebody tries to put something into a neighborhood, people get angry, so it's there, it's at a level maybe below consciousness but it emerges when something, when people are being threatened. And I think if people could only see how all of these are tied up and at how dealing with all of these will give us what we really want and begin to recognize, too, that the technology, the industrial society is not the bad thing, it's just who's using it and who's being used that's bad. Then I think that we can achieve the kind of end. I think young people, particularly, should begin to think in terms of extracting what's best from this society and then making it work for them.

Studs Terkel In short, then, what we've been listening to are not so much pat offerings or answers, rather reflections that we trust must lead to action. And when we quote, what did we call this, "quality of life," it's a general phrase, and, yet, it's just right, too. This is the second session we've had, perhaps one more, too, it's very delightful, of course, having Dr. Bertram Carnow and Bob and Joan Ericksen as my guests, and thank you very much.