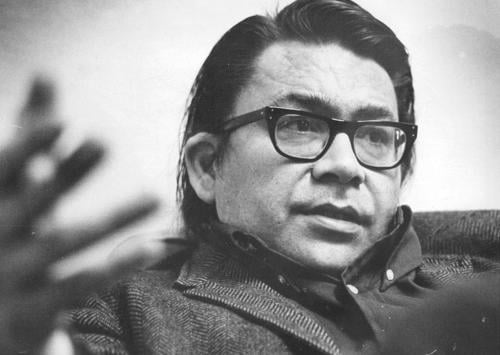

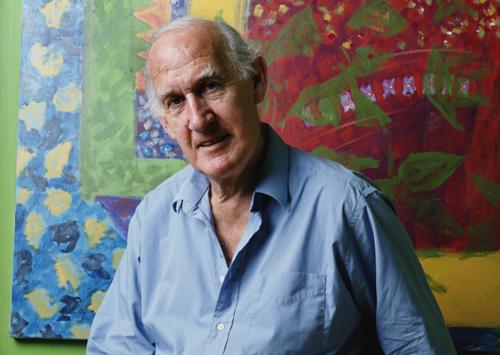

Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward discuss the book "All the President's Men"

BROADCAST: Jun. 21, 1974 | DURATION: 00:55:03

Synopsis

Washington Post journalists discuss their book "All the President's Men" about breaking the Watergate scandal.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Studs Terkel There's a great deal to talk about Orwell, "1984", of mechanical men and perhaps we'll all become machines and - and we feel kind of low at tim- What's going to happen? All of a sudden something explodes and something in the person of two young investigative reporters, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. And the book, as you know, is "All the President's Men", and they broke the Watergate case. And it occurs to me that this book is one of several dimensions. It's a suspense book. It's great police reporting. It's two young crime reporters, you might say, investigating a gang of thieves, it could be that - the Mafia, the Syndicate - as is done. It also is how a newspaper works and it involves the - what was happening in the office of "The Washington Post" with the two reporters, Bernstein, Woodward, and the editors and the associate editors. And also it involves the relationship with the two guys themselves. But it involves more than that to me. It involves flesh and blood guys, who are excellent journalists, against what seems to be a machine. So, when did the case break? You first heard about the case - it's 1972, Bob, was it?

Bob Woodward Well, the first I became acquainted with the Watergate burglary was early the morning after the five men had been arrested there, when the city editor called me and said "Come in." And the the real feeling that the story was going to be something was when James McCord in the courtroom whispered "CIA."

Studs Terkel "CIA." And then there was Carl Bernstein. You and he had never worked together before. You two were metropolitan reporters and not national reporters.

Carl Berstein Correct.

Studs Terkel And both you [became?] to work on it. But at that time - now here's a voice, he's a professor of communications, God help us. That's what he is, [laughter] and he's telling about how good Nixon is in handling people and stifling - Would both of you hear this voice of this professor? At the time you had - you two guys had just got on to something.

Carl Berstein This is right after the major period of the disclosures that were in the Washington Post.

Studs Terkel So here's the voice.

Professor Jack Hunterr I think, from what little I can find out from people who have studied Nixon in our field, strictly on an academic basis, you know - reporting, reporting what we know to somebody else who we know, rather than to the public - Nixon uses his people wisely and gets the information, whether he wants to hear it or not, that will help him. And that he will avoid certain kinds of behavior and to be attracted to certain kinds of messages, certain kinds of themes. I think in the last four years, the Nixon administration has so carefully softened the power of the press that the press is taken more lightly than ever before in its existence in my mind. That's, I think, why the Watergate affair was so delicately brushed aside by the American people.

Studs Terkel Now as we listen to the voice of Professor - I call him Jack Hunter - you, both of you read parts of the book. The book is written sort of third person, isn't it?

Studs Terkel And suppose Woodward tells about Bernstein's revelation when he first came to it and Bernstein, you Carl, tell about Woodward's. So--

Bob Woodward The book really is the story of the newspaper business and reporting, and it it starts out that first day in June 17, '72 and tracks us and "The Washington Post" through the story as we learn a more incredible piece of the puzzle and write stories for the paper. One of the most interesting parts, per- perhaps in the book, is a section that in a sense deals with the press on how the White House is responding, how they are stonewalling us. And besides not responding to stories, they're they're denouncing "The Washington Post" and saying we're printing hearsay, character assassination, and innuendo. And at this point in the book on page 105 we just involved John Mitchell in the story and received what we call a non-denial denial from the White House, namely an attack on the newspaper, really. A denial that sort of it's true, but really not speaking to the issue. So Carl decided to call John Mitchell at his home in New York. Do you want to lead in with anything on that, Carl?

Carl Berstein Only that, that it was perhaps the most important story up until that point. It said that John Mitchell, the former attorney general of the United States, that while he was the nation's top law enforcement officer, had controlled the secret funds that that funded the Watergate operation and other undercover activities.

Bob Woodward And these are from Carl's notes as he wrote them that night after the conversation: Got Mitchell on the phone. He answered. Mitchell: "Yes." Bernstein, after identifying himself: "Sir, I'm sorry to bother you at this hour, but we are running a story in tomorrow's paper that in effect says you controlled secret funds that the Committee for the Re-Election of the President while you were attorney general." Mitchell: "Gee [pauses to imply profanity] you said that? What does it say?" Bernstein: "I'll read you the first few paragraphs." He got about as far as the third, and Mitchell responded again: "Geez, [pauses]" after every few words. Then Mitchell said, "All that crap you're putting it in the paper? It's all been denied. Katie Graham," referring to the publisher of The Washington Post, "Katie Graham's going to get her tit caught in a big fat ringer if that's published. Good Christ, that's the most sickening thing I've ever heard." Bernstein, who, by the way, I might add is not used to talking to the former chief law enforcement officer of the United States, Bernstein said, "Sir, I'd like to ask you a few questions about-" Mitchell interrupts: "What time is it?" Bernstein: "11:30. I'm sorry to call so late." Mitchell: "11:30? 11:30 when?" Bernstein: "11:30 at night." Mitchell: "Oh." Bernstein: "The committee has issued a statement about the story, but I'd like to ask you a few questions about the specifics of what the story contains." Mitchell: "Did the committee tell you to go ahead and publish that story? You fellows got a great ball game going. As soon as you're through paying Ed Williams" - a reference to the attorney for the Washington Post - "and the rest of those fellows, we're going to do a story on all of you." Bernstein: "Sir, about the story." Mitchell: "Call my law office in the morning." And then Mitchell hung up.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein You know, what's so interesting about the conversation in retrospect is that that occurred on September the 29th. And, of course, the White House transcripts show the president and Dean talking on September 15th in very much the same terms and specifically taking action involving Ed Bennett Williams, who's referred to in that discussion as "that, that son of a bitch Williams."

Studs Terkel What interests me also, by the way, is both of you, the acuteness of both you in picking up revelations unintentional, apart. Now Mit- Mitchell obviously was astonished, wasn't he, when you, Carl Bernstein, called him? That that that it broke, isn't that it?

Carl Berstein Well, I I think that his reaction - we describe it in the book somewhat - is is almost a "Jesus" as being some kind of primal scream. We had done, we have said the words out loud that the grand jury hadn't said even though it might have had some of the same information.

Bob Woodward When he said the "Jesus," I I think we thought it was a prayer. But--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein But he was obviously in some kind of excruciating pain knowing that that finally somebody had had in essence said the former attorney general has broken the law.

Studs Terkel That's why we had that mechanical-sounding voice in the beginning of the guy who says, "Everything's set. Nothing the press can do", and so on, but--

Carl Berstein The reaction was rather rather consistent. The other passage that that you pointed out yourself here, discussion between Bob and a source known as Deep Throat, who was perhaps the most sensitive source that we had. He occupied a high, sensitive position in the executive branch of the federal government. The passage begins, "Woodward nodded. 'How'd the Post like its subpoenas?' Deep Throat asked, 'Just great,' said Woodward. 'That's only the first step. Our president has gone on a rampage about news leaks on Watergate. He's told the appropriate people, go to any length to stop them. When he says that he really means business; internal investigations, plus he wants to use the courts. There was a discussion about whether to go the criminal route or the civil suit route first. At a meeting Nixon said that the money left over from the campaign, about five million dollars or so, might as well be used to take the Washington Post down a notch. Thus, your subpoenas and the others. Part of the discussion was about starting a grand jury investigation. But that's for later. Nixon was wild, shouting and hollering that we can't have it and we've got to stop it. I don't care how much it cost. His theory is that the news media have gone way too far and a trend has to be stopped. Almost like he was talking about federal spending. He's fixed on the subject and doesn't care how much time it takes. He wants it done. To him the question is no less than the very integrity of government and basic loyalty. He thinks the press is out to get him and, therefore, is disloyal. People who talk to the press are even worse - the enemies within or something like that.'"

Studs Terkel Isn't it funny, as you're talking, both of you, the press and the reputation it has - the credibility, an overused word - and what you did to suddenly make something else incredible, unbelievable and that's those that put down the press.

Carl Berstein The point that you're - that the professor who we just heard on tape made is a very valid one. This administration was singularly successful in undermining the credibility of the press. I think you can trace it back perhaps as far as when Vice President Agnew, then vice president, made a speech in Des Moines, Iowa, in which he called on the press to use its powers of investigation for the purposes of some self-examination. A statement which I think Bob and I agree with, but perhaps for different reasons than Mr. Agnew.

Studs Terkel See, which is what I find more astonishing, Carl and Bob, about your book, which I find a very important book, is that the press was never really that great. You and I.F. Stone know it, you know. It was never that great, I'm talking about the White House correspondents. You have a marvelous, a very pertinent footnote here somewhere that quoted John Osbourne how the, how the press is snowed by the presidency and certainly snowed by Kissinger.

Bob Woodward Well, in in the Mitchell conversation that that Carl had, it it, where Mitchell says at that point, "did the committee tell you to go ahead and publish that?" It's almost as if they have the power to say, "okay, that can go in the paper and that can go in the paper." And, I I guess the point of the, of the book really is, because it is that story of journalism, that you have to sort of go toe to toe with these people. You have to say, our sources say this, we have the following information, and you can deny it, you can threaten the publisher with having a portion of her anatomy going through the ringer, but nonetheless, you put it in the paper.

Studs Terkel Now we come to how you two worked and the obstacles you faced. And you have a little dedication to - it's called "All the President's Men", Simon & Schuster the publishers - but you dedicate to those, not all, some of them had the courage, and to tell you things. Now we come to the big wall you had to scale: the fear of people, the incredible fear of those revealing. Wasn't that the big one?

Carl Berstein Interestingly enough, it was - even though we weren't getting much information when we first encountered this fear, it told us something that we didn't know, and that was that the stakes of Watergate were much higher than we ever perceived. This was in August and September of '72. The White House and the Committee for the Re-election of the President were still vehemently denying any connection whatsoever with Watergate. And we went around and started visiting the homes of of low-level White House and Committee for the Re-election of the President employees, and doors were slammed in our faces. But very often before the doors were slammed, someone would say something like "You can't be seen here. They follow me. I'm afraid they've got my phone tapped. There are terrible things going on but I can't talk about them." And that fear told us something that we, that we really didn't perceive until then.

Studs Terkel Now, these were people - a woman you call the bookkeeper, different ones, we come to Hugh Sloan, the most sympathetic of the people - But [unintelligible] you had to get your foot in the door, didn't you? I subtitle the book "Foot in the Door", by the way [laughter].

Bob Woodward Well well, one of the interesting scenes in there is where Carl learns that there is this bookkeeper who may know something, somebody who worked for Maurice Stans may know something about all this loose cash that seemed to be floating around, because we had just done a story about a 25,000 dollar campaign check that went in the bank account of one of these burglars. And that was really the first major story that that made it clear to us that there was something here. And when Carl went to the the bookkeeper's house, Carl identified himself and the bookkeeper said, "Oh no, you've got to go away, you can't be here", and gave the standard routine. And in order to get a foot in the door, Carl saw a pack of cigarettes, I guess, laying on the table--

Bob Woodward And says "Can I have a cigarette?" And then she, being a kind person, said, "Okay, here's a cigarette" And then the bookkeeper had her sister there, I believe.

Studs Terkel Coffee.

Bob Woodward And the sister said, "Well", you know, "well, would you like some coffee?" And Carl said, "Yes indeed," and then drank one of the slowest cups of coffee in the history of coffee drinking [laughter].

Studs Terkel The question, isn't it now, you're talking to us now about people - Now some of the people are doing this work - we're talking about, we're talking about a mechanical situation - are basically decent people like this bookkeeper, caught, isn't that it?

Carl Berstein Very much so. Certainly there were a lot of fine people who worked for the Committee for the Re-election of the President, who still work in the White House, and and the bookkeeper was one of them. There's a very interesting part again in the White House transcripts. It's very interesting how the transcripts have illuminated kind of parts of the book where John Dean and the president are talking, and and John Dean starts to talk about this little pocket of secretaries in in the Office of Maurice Stans and what a potential problem they are. Well, we were fortunate enough in the case of the bookkeeper and some other people to to get into that pocket, and it was there that that we've started to learn about the money. And the money told us that, yes, there had been a secret fund that financed these activities. And and that put us on to who controlled the secret fund which is--

Bob Woodward Really put us on to to Hugh Sloan who probably takes up 70 or 80 pages in the book and--

Studs Terkel For the first time his name is revealed in this book, that he was your source aside from--

Carl Berstein A source, right.

Studs Terkel A source, aside from Deep Throat.

Bob Woodward One of, written, many many sources.

Bob Woodward But a key source. And again the process is - and I think probably for people who don't know much about newspaper reporting, it's revealing that these unnamed sources are not people who are the classic leakers, who want to come in and say here's the whole story, but people who are in privileged positions caught with divided loyalties, and you prevail upon them. As Carl has said, we sort of felt like vultures going out to Sloan's house, the the dozen or more times we did because he was always so reluctant. But you could get in and, and have a cup of coffee and then he'd maybe tell you a little something.

Carl Berstein And once once you have one piece of information, you can use it to pry loose another piece of information. That's really, I think, the key to to this kind of reporting and it's a step-by-step--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein Slow, excruciating extraction process.

Studs Terkel I think it should be pointed out, it's quite obvious that what Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward did is very tough, investigative sloughing through the mud in every, the mud in every sense, you know, work.

Carl Berstein The real point is it's not about leaks.

Studs Terkel No.

Carl Berstein And I think we're hearing a lot, too much about leaks now.

Studs Terkel Yeah, yeah. You guys connected seemingly disconnected events and suddenly it all came to pass.

Carl Berstein Right.

Bob Woodward And and that's what really made Watergate more than just a burglary at the Democratic headquarters. And it was that connecting of events that we were able to do through the information we got from our sources that made it clear that secret operations in the White House were were the order of the day, really, and that the Segretti dirty tricks operation was related to Watergate.

Carl Berstein What what happened is really a funny kind of thing that, we didn't get many anonymous tips from people calling in that we didn't know. But one night, a gentleman called me who said he was an attorney for the government. No connection with any of the Watergate matters. And he said he had heard this rather crazy story from a friend who was approached by a friend to do some work for the Nixon campaign in a rather unusual way, which is to say to go around and sabotage the Democratic primaries. And he gave me the name of his friend, a gentleman named Alex Shipley, who was an assistant attorney general--

Studs Terkel Tennessee.

Carl Berstein In the state of Tennessee. And I got hold of Shipley, and he proceeded to tell me this rather bizarre story about the travels of Donald Segretti, a young California lawyer who had just gotten out of the army and who had attempted to recruit Shipley and others to conduct some rather vicious political sabotage and espionage during those primaries. And it suddenly, to us, started to make some sense out of Watergate. At this time, Watergate was an isolated incident. Nobody could really understand why Watergate on June 17th when the president's reelection seemed all but assured. But if it was part of something larger, it made sense. And in the course of a routine conversation with a government official who was concerned with the case, a government attorney, I just sort of threw out the name Donald Segretti and, expecting to get no response, and the government attorney went into a rampage. He was just furious.

Studs Terkel You found out something.

Carl Berstein And said that if you could find out about that kind of conduct and about Segretti's operation, it would really tell you something that, that would stagger you.

Studs Terkel Now I'm thinking, just let's stick with the Segretti thing because to me the book has so many dimensions. You talk about Segretti and the group of guys who were at the University of Southern California.

Carl Berstein Right.

Studs Terkel And they were doing little tricks, you know, but suddenly become big tricks, and the "Kiddie Corps" of young - he hired young kids, right? To penetrate the Quakers, to be agent provocateurs, right? And you ask one of the kids about, "how do you feel about ethics", you know. "What do you mean ethics?" You know, you see to me this is very important, too, in your book. There's a new kind of something in our society. Maybe it's always been, but this horrendous amorality. That's also what that you find out, isn't it?

Carl Berstein There certainly was a good deal of amorality, I think, in the way this campaign was conducted.

Studs Terkel I'm talking about the way, the using of young people, too.

Bob Woodward That that that was one of the most outrageous things, really, and it wa- and it obviously to the to the young people who were approached to do this - somebody called it sandbox politics, really. But it was, it was sort of kid stuff and some of it seemed just to be pranks. But then you really looked into it, and some of it was extremely vicious--

Carl Berstein The Committee for the Re-election of the President went so far as to attempt to fix mock elections in high schools.

Studs Terkel This is the point, it's almost a burlesque in a way. It's almost like a musical comedy, if it weren't so--

Carl Berstein If it weren't so tragic.

Studs Terkel If it weren't that, if we weren't so close to a police state. Now what would have happened - this is a con- conjecture, I'm just - what would have happened if you guys didn't break it? I'm curious, [after?] Watergate, as our friend in the beginning said was buried, you know.

Bob Woodward Well, it was it was a process of interaction between the press and the the numerous government investigations, and it's a very iffy question. We did some of the stories, but "Time" magazine, "The New York Times", others did a lot. And it really brought Watergate to the pitch, and particularly in the Segretti activities, which the Justice Department refused to investigate, that led Senator Ervin - and there's described an interview I had with Senator Ervin about this before he set up his committee - who said now this is something we've got to look at. What, who is tampering with the political process? And then he set up his investigation and then led to the events forming the special prosecutor and the and the impeachment proceeding. So it was always, not only evolutionary from the point of view of the evidence we gained, but who was the investigative agency or agent.

Carl Berstein Another thing that, that I think had a lot to do with this was that the stakes were raised, perhaps to a point of no return by by the White House deciding that it would make the the conduct of the press the issue rather than the conduct of the president's men. By attacking us, attacking "The Washington Post", in particular in the manner and intensity that the White House did--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein It, it made this an irredeemable game, as it were, that if one side turned out turned out to be wrong that side, its credibility, was gonna be gonna be if not destroyed, certainly impaired tremendously.

Studs Terkel You know, there's also in your book as - throughout there's this question of the investigations of of Bernstein and Woodward, that's now celebrated and known and it should be, I hope, you know, even more known - that there was a human aspect to it. You yourself had ethical problems, too. We come to that, don't [unintelligible]?

Bob Woodward Oh, oh yes indeed. We went into a period after we had made an an error on the H.R. Haldeman story, which was an error in attribution, saying somebody had testified before the grand jury that Haldeman controlled this secret fund. In fact, he had controlled it and as his indictment suggests, there's some serious allegations against him. Nonetheless, we had said that somebody had so testified, and they had not, and the White House was able to attack that story quite effectively and then--

Studs Terkel Yeah. That was a critical moment for you guys, yeah.

Carl Berstein It's probably the worst moment we ever had.

Studs Terkel Because then the question is, are you guys going to be tossed in the can for one thing, like [unintelligible].

Carl Berstein We, we considered resigning, as a matter of fact--

Carl Berstein Because it it was - although the substance of the report was accurate, the stories had been building. We had a pretty much airtight track record, and then all of a sudden, it was just as if the ground had been cut from under us.

Bob Woodward And in this, in the the desperation of that day when we - it became quite clear to us that we had made this mistake in attribution, we went around to check with the sources of information, one of them being an FBI agent, and he wouldn't talk to us about it, and we felt both responsible and desperate to to find out how we had made this mistake. And so we went and told the agent's boss that the agent had talked to us. And this, in a sense, was really blowing a source. The man did not get in trouble, thank heavens, but it's something that, my God--

Carl Berstein Absolutely unforgivable. I mean, I think it's something we'd never do again.

Studs Terkel I'm thinking, I'm thinking even deeper than that, and that's Carl - and to get the records from the telephone company, I'm thinking of. There again now, I realize the situation. This is something we're, we're faced at a certain moment--

Carl Berstein Well, what's so interesting to me is that--

Studs Terkel Could you explain that?

Carl Berstein We were confronted with ethical problems--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein Not unlike people with at White House very often were.

Bob Woodward Tell him about that telephone record and what it was for.

Studs Terkel The telephone was very important.

Carl Berstein And very early, this was in July, only a month or six weeks after the break-in, I attempted to to get some telephone records of Bernard Barker--

Bob Woodward One of the Watergate burglars.

Carl Berstein As well as some credit card records. In fact, I also used credit card records on Segretti, and in both instances I was able to get the records. And I kept wondering to myself if this was, you know, if they were records on me, I'd be outraged if I knew a reporter had been able to go to AT&T or to go to a major credit card company and get this information, which is supposedly confidential. That gets into a whole question of when do the ends justify the means, which, of course, has a lot to do with Watergate and the whole mentality behind it. And we were constantly faced with with that same kind of question.

Studs Terkel Yeah. What a hell of a--

Carl Berstein And we don't know the answers.

Studs Terkel Yeah, but yet you had to. If you didn't get those records of Barker or those Segretti expenditures, or whatever, you wouldn't have been able to go follow through, yeah.

Bob Woodward That's right. And the and the main example was visiting grand jurors, which in the desperation after the Haldeman error is is Ben Bradlee, the editor at the "Post", said he was gonna to hold our heads in a pail of water until we came up with the story. And in in that desperation we went around, talked to grand jurors, something that is not illegal, but certainly something highly questionable getting into that secret process.

Studs Terkel We'll come to a humorous moment in that, too.

Carl Berstein Fortunately, we got no information whatsoever from the grand jurors, which would have compounded the problem, if we had.

Studs Terkel And then Sirica - oh, this is a very funny scene there. Perhaps, perhaps before we take a slight break--

Carl Berstein Wasn't funny if you were there.

Studs Terkel Yeah, it wasn't funny [chuckling]. A slight break, though, before we take a slight break, the idea of Sirica had found out he was bawling out a couple of correspondents. A lot of journalists were there, right?

Studs Terkel And he's bawling out, and didn't know it was you guys that did it.

Bob Woodward You wanted us to tell that now or later?

Studs Terkel Yeah, well that now and then we'll take a slight break.

Bob Woodward Oh, okay. It was a situation where some of the people that we approached, one or more, went to the prosecutors and said these reporters are coming around asking us to break our oath, and prosecutors went to Judge Sirica, who was outraged and told our lawyer that we'd better be down in the courtroom--

Bob Woodward A couple of days before Christmas. We went down there. I got a haircut, and we put on our nicest suits and we figured we were headed for for jail or at least a a public unveiling that we were not looking forward to. Judge Sirica came out and said a member of the news media had approached the grand jurors, and and issued a lecture and commended the grand jurors not for talking and then left the courtroom and did not name us. And there were about 30 correspondents there.

Carl Berstein And there was this kind of mad rush to the hallways in which the the various reporters start asking each other whom they suspected and was it was you, was it you, and and we in effect engaged in our own cover-up. We--

Studs Terkel You say, you guys, "Who me? How dare you!"

Bob Woodward That's right. We sounded like the worst in the White House.

Carl Berstein We evaded, misrepresented, dodged, ran for the elevator.

Studs Terkel Here's the crazy part, about the same time, a guy named Lawrence, John Lawrence, the "L.A. Times", was protecting a source, you know, in the tradition of the free press, he gets put in the pokey.

Carl Berstein That's correct. That same day by the same judge.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Bob Woodward And I remember coming back from that hearing just totally split.

Carl Berstein I've never seen Woodward so totally shaken.

Studs Terkel Yeah, yeah. I would say. Bernstein had rarely seen Woodward so shaken, both painfully aware of the contrast. So a slight pause here as we're talking to Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, and the book is "All the President's Men" that Simon and Schuster have published. I think you could say it's more than a suspense story of the work of two investigative journalists, but it's about our society, too, and where to, what next and and what have we learned from Watergate. But more of this and the techniques in a moment after this pause. [pause in recording] Resuming the conversation with Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward and "All the President's Men". Talking about how you got things and the telephone. People tell you things, a phrase and so they mean to, like Judge Robie. Early in the case there's a federal judge.

Studs Terkel Richey. I'm sorry. And what - this is, to me, fantastic. He he told you something. You - he called you, didn't he?

Carl Berstein Correct.

Studs Terkel This is what he said, the stuff - this is during the campaign, election [unintelligible].

Carl Berstein This is while the Democrats' civil suit was being argued. The Democrats had filed a civil suit against the Committee for the Re-election of the President stemming from the break-in. And the purpose of the suit was really not so much to win money damages as to get disclosure through calling in officials of the Committee to take their depositions. And inexplicably, Judge Richey on August 22nd, 1972--

Bob Woodward He was the judge hearing the case.

Carl Berstein Right. Judge Richey reversed a decision that he himself had made a week earlier and ordered all the depositions sealed and that no further testimony be taken until after the criminal proceedings had finished, which in effect meant that there would be no disclosure under oath before the election. And then later that day, he called me, and I had never talked to the judge in my life. And he said, "I just wanted you to know that the reason for this was to protect everybody's civil rights and liberties, and it had absolutely nothing to do with any ex parte communications."

Studs Terkel You never asked this, did you?

Carl Berstein I never asked. It was like a bolt out of the blue. The idea that anyone would approach a federal judge to me was was unthinkable.

Studs Terkel Because because there's this question is left hanging, isn't it? Was--

Bob Woodward Well, there are allegations - John Dean's testimony - that a lawyer named Roemer McPhee in Washington had acted sort of as go-between the Committee for the Re-election of the President and the judge. The allegations have been denied, and there's really been no resolution of that.

Carl Berstein John Mitchell testified that indeed there had been, I think, almost a dozen meetings, although John Mitchell said that the purpose of the meetings was perfectly proper.

Studs Terkel You're talking about a tangled scheme that you guys are untangling about how how how profound it is and horrendous, you know. Then the news - I'm thinking about how you guys work. So, some guy leaks something and the name Ehrlichman came in on page 237 here. Some guy's talking to you on the phone and suddenly Woodward snapped a pencil in half between his fingers. The guy dropped the name you didn't expect him to drop.

Bob Woodward That's right. And Ehrlichman really had the reputation as the program man in the White House. Very human person, not rigid like Haldeman was supposedly. And for someone to bring Ehrlichman in again and to suggest that his name might come out at the Watergate trial was rather astonishing. Deep Throat had earlier told me, in fact, that Ehrlichman had ordered Howard Hunt out of the country and sort of with this this excess of caution - I really shouldn't call it an excess, I think it was appropriate - but we we kept things out of the paper until we could, we were absolutely sure--

Bob Woodward And this is something Carl would try to get in a story or two and--

Carl Berstein Woodward would keep keep killing it. We had a rule that we wouldn't put anything in the paper involving improper activity or allegations unless it was confirmed by two independent sources. Meaning really from different ends of the spectrum, which is to say if somebody in the Committee for the Re-election of the President told us that John Mitchell controlled some fund, we'd have to have that information either from someone in the FBI or in the Justice Department or someone in the White House with firsthand knowledge of it, just so we could nail all the corners down and know that we were perfectly safe.

Studs Terkel Yeah, yeah. There are some marvelous moments of humor here, too. You two guys fighting at the water cooler. There's also a part, now I'm curious, did the guys in the city desk - we'll come to the question of you guys being local reporters - the guys around the all know you were working on this, and they kept it pretty well on the--

Carl Berstein We kept the information as closely held in the office as we could. Once it reached the point where we saw that it, that it was going in unprecedented directions - I remember the day probably of the most important story the, the October 10th story, which said that Watergate was just a small part of a massive campaign of political espionage and sabotage, gradually the word started to go through the newsroom that there was a package of stories that was coming that was going to sort of go like a rocket through the White House, and there were editors coming around and peering over everyone's shoulder.

Bob Woodward The the role of the editors in this story is very interesting and really after the sources and and after ourselves in the book, the main characters are--

Studs Terkel This is Bradlee and Simons and Sussman.

Bob Woodward That's right. We had--

Carl Berstein Harry Rosenfeld, the metropolitan editor.

Bob Woodward We had four editors. First, we were assigned to the local desk and still are, in fact. The immediate editor, a a fellow named Barry Sussman, who was really sort of the conceptual editor, worked with us very, very hard on these these stories and would always ask the question, "Okay, you've written this story, now where does it go? Who do you need to talk to? How does this fit in?" Then immediately above him is the metropolitan editor of "The Post", Harry Rosenfeld, who's really sort of somebody out of "Front Page". He runs around the newsroom screaming and yelling, very demanding, insistent man, but at the same time probably the supreme expert on reading a story and seeing a hole in it. Then after him is Howard Simons, the managing editor, a meticulous form- former science reporter who sort of acts as a break, a very, very cautious person.

Carl Berstein He'd tell us a lot: when in doubt, leave it out. That really was the, was the rule.

Bob Woodward And then Ben Bradlee, the executive editor, very sophisticated old-timer who's been around Washington and the journalism profession for about 25, actually more like--

Studs Terkel And now we come to something else here, little conflicts and two different approaches. Bradlee is very much like Bob Woodward. He wants hard fact. You want hard fact, right? Whereas you, Carl, were working on hunches, intuitive stuff, is that it? Isn't that the idea? There was--

Carl Berstein Yeah, I like to deal in deduction and--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein And and to sort of get an idea where I'm going next and follow that direction. Bob much prefers hard information. He's impatient with theories. Bradlee's the same way. What's so interesting is that within "The Washington Post" that you had both reporters and editors whose skills kind of complemented each other and who served as brakes on each other.

Bob Woodward But the the the the buck really did stop with Bradlee. He was the, as the number one editor, the person who had to sit in there each night and read over the story, interrogate us somewhat like a prosecutor.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Bob Woodward And say "Where'd you get that? What exact- what'd they say."

Studs Terkel Because he had his fingers burned once, didn't he? When he was at "Newsweek", see? That's it. And he wanted to make sure you guys got it, and that's some- when he--

Bob Woodward Actually, that was another--

Bob Woodward That was another sort of incident of - it, it was when we learned that Dean and Haldeman were going to have to resign from the White House staff, and we we learned this about two weeks before it happened. And we were thinking of writing the story and Bradlee recalled when he had, working for "Newsweek", written a story that J. Edgar Hoover was going to resign and going to be replaced--

Studs Terkel He got it, he got it from LBJ's press - he got it--

Carl Berstein He had gotten the story from Bill Moyers--

Carl Berstein Who was Johnson's press secretary. And Bradlee went ahead and wrote the story, put it in "Newsweek", and Mr. Hoover apparently was very successful in resisting. And the next thing that Bradlee knew, Lyndon Johnson told Bill Moyers, "Well"--

Bob Woodward No, Johnson held a press conference and--

Bob Woodward Appointed Hoover FBI director for life. And as he walked out, he learned, leaned over to Moyers and said, "You call up Ben Bradlee and tell him expletive deleted you." [laughter]

Carl Berstein That you just got him appointed for life.

Studs Terkel By the way, let's stick with, let's stick with the FBI for a moment and Hoover. It's interesting, the role of the FBI, or the flaccid role. Oh Hoover, by the way, threatened to expose the taps, didn't he, if he were forced to resign?

Bob Woodward There's an allegation to that effect, the the 17 wiretaps on government officials and news reporters.

Studs Terkel But coming it back to the FBI. You you guys were also impelling something to happen. Somewhere along the line this stuff wasn't really coming out as much as it should be, should it?

Studs Terkel That, was the FBI really doing its job, you know.

Carl Berstein Well, certainly we would call people and find out that they hadn't been interviewed by the FBI. Good example was Jeb Magruder's secretary had never been interviewed by the FBI. Robert Reasoner, Magruder's principal assistant, who we now know was the person who who took the the gemstone file, the actual wiretap file the the weekend of the break-in. It was in his possession for a while. Magruder asked him to take it out of his desk. The FBI had never talked to him. We will go through address books that were introduced in evidence at the trial and call the telephone numbers in them. And people would answer the phone and say, "Oh, the first I ever heard of it. Never heard from the FBI."

Studs Terkel And also the prosecutors, Silbert and those guys weren't really doing a job, you point out here. Some guys were telling you that.

Bob Woodward Well, it's, now that's one of the most complicated things to unravel, the role of the prosecutors in this case. They they did a lot of things right, but I think there was, either a certain timidity or naivete almost, and not understanding the the lines of authority in the White House. Not--

Carl Berstein They were manipulated also, I think. You know, again the White House transcripts show that. I think no one has questioned the integrity of of the three prosecutors. I think they're men of unquestioned integrity. But interestingly enough, I think that that where we perhaps were were a little bit more successful than the prosecutors was in understanding the atmosphere of the White House, the lines of authority there, and the same in the Committee for the Re-election of the President. Deep Throat, at one point in the book, refers to it as the "siege mentality", and had the prosecutors been much more aware of that mentality than they were and the lines of authority, I think perhaps that that they wouldn't have been manipulated quite so readily.

Studs Terkel You're talking about a siege mentality, Deep Throat. Now we come, now the stakes are getting higher and higher as you guys are putting it together more and more. Now the fear is getting - and when the name Haldeman came into play - that's when it underwent almost a quiet change.

Bob Woodward Everyone ducked for cover, because he is the president's number one assistant, ran the White House with an iron hand. And that is one of the things that that we learned, and and it became quite clear to us that there was very little that went on in the White House that Haldeman didn't either approve or authorize or know about. And this is one of the reasons for the - if if you have to fault the federal investigation, it was the unwillingness to investigate the Segretti activities. As you may recall, Segretti, one of his contacts was Dwight Chapin, the president's appointment secretary, who was paid by Herbert Kalmbach, the president's personal attorney. Now these are very, very high people, but they wouldn't look at at that. They interviewed the people, and then they stopped.

Carl Berstein And they knew in that case. For instance, there's a conversation in the book where I speak with a government attorney who's obviously concerned with the case. And I used the the old USC term for the type of political espionage and sabotage that was conducted. The term was [edited tape], and I mentioned the word to this government attorney and he said, "[edited tape]". He says, "You can go right to the top on that one", he says. And I say, "You mean Mitchell?" And he says, "Higher than Mitchell even. All the way to the top."

Bob Woodward But they, Kleindienst quite quite with a great deal of pride at this point, came out and said, "We're not invest- investigating that stuff. That's dirty tricks."

Carl Berstein Political pranks.

Bob Woodward And, and it's now clear. Segretti pleaded guilty to to violating the law in a number of cases on this. And I mean some of it was was vicious, vicious material putting out those letters.

Carl Berstein Right. And Segretti had been hired by Dwight Chapin, the president's appointment secretary, and with the approval of Haldeman as Mr. Haldeman later acknowledged.

Studs Terkel You're talking about pranks. Remember when that case first broke. You guys were working on it now. We didn't know you guys were that deep in it. The word "caper" was used, and the word "caper" has a light quality to it, almost a musical comedy quality, Lavender Hill Mob quality, doesn't it? That's not really serious. I was very impressed with that in a negative way, the fact that the word "caper" was always used, not serious.

Bob Woodward Actually that's a term developed by Jack Anderson, the investigative reporter, and he quickly disposed of it. In in in a sense you look at it, five of these guys--

Carl Berstein It seemed like a caper at first. It it wasn't until after August 1st and then after October 10th that you really began to understand the dimension of this thing.

Bob Woodward That that August 1st being the story about the 25,000 dollar campaign contribution that--

Studs Terkel What it adds up to is the destruction the whole electoral process, [unintelligible] of everything.

Carl Berstein

Bob Woodward [Exactly?]. Potentially.

Studs Terkel But there's something else here that's funny and strange. You got to Clawson who was once a colleague of yours, right? He used to work for "The Post"--

Carl Berstein Correct.

Studs Terkel And now is working for, for the citizens, citizens committee.

Carl Berstein At the time, Ken Clawson was the Deputy Director of Communications at the White House.

Studs Terkel But, here's here's a marvelous and funny comment on morality, [unintelligible]. He was involved with the Canuck letter, the framed letter that could have destroyed Muskie.

Bob Woodward Allegedly.

Studs Terkel Allegedly.

Bob Woodward Yes.

Studs Terkel But he wasn't worried about that so much as a girl reporter, he visited a girl reporter's apartment where she has many visitors. And that's what was bothering him.

Carl Berstein That's--

Bob Woodward That's laid out in some detail-

Studs Terkel I think that's a very

Bob Woodward funny scene. In the book.

Carl Berstein It's a hilarious conversation in there between Marilyn Berger, the reporter in question, and Clawson, in which - what had happened was that Clawson, according to Marilyn Berger, had told her that he wrote the Canuck letter. Subsequently, he denies--

Bob Woodward That, we should describe the Canuck letter. It is a letter that supposedly was written to a New Hampshire paper just before the, that very crucial primary alleging that Senator Muskie, then the front runner, had condoned the race- racial slur against French-Canadians of of of Canuck, and it was very celebrated and one of the factors that led to Muskie's crying speech.

Carl Berstein And Clawson, according to Marilyn Berger, who told us the story, came to her apartment and said, "I wrote the Canuck letter." He subsequently denied and said there must have been some misunderstanding, but when we went with this rather huge story that combined the Segretti operation and the Canuck letter and some other dirty tricks, Clawson seemed much more concerned about the fact that he was in Marilyn Berger's apartment having a drink than anything about the activity itself, to the point where at one point he says, "Marilyn, don't you understand I have a wife and a dog and a cat?"

Studs Terkel You know, what hits me about that is, what is morality? You know Gore Vidal's play "The Best Man." Our version of morality. The version we have is man, woman and boudoir. That's amoral, you know. But the idea of knifing people and gypping people is not amoral. That's what I'm talking about.

Carl Berstein Well, certainly within the Nixon White House, again getting back to a siege mentality, that anything was considered fair game. That if you - Hugh Sloan describes this rarefied atmosphere in the book. That you thought you, you really had the power and almost a responsibility to do anything without worrying too much about the law.

Bob Woodward Well, in talking about the Canuck letter, Clawson is, in later denying that he wrote it, said that he told Marilyn, "I wish I had written it."

Carl Berstein Right [laughter].

Bob Woodward Which sort of conveys [laughter] the whole notion that it, it's a dirty trick that that seemed to be a factor in knocking Muskie out, who is really the person that the White House feared.

Studs Terkel You know if one does it effectively, no matter how vile it might be, but does it well [by you succeed?]. You know, "I'm a bastard, I admit it", well, you've got to give me credit.

Carl Berstein That's how you earn your spurs.

Studs Terkel Yeah. So we come to more and more as the case is built, you guys are getting it put together more and more. Fear is also, fear is also being compounded, isn't it? The fears now.

Carl Berstein I think there there were two levels of fear. One was our own occasional paranoia, and the other had to do with the fear of losing our credibility and also that that the White House had the ability to retaliate against "The Washington Post"--

Bob Woodward And and also I think you're talking about the the the fear in in the president's inner circle among even the secretaries and aides that somehow somebody's going to unravel the sock. And we we now know, it's now clear why there had to be a cover-up in Watergate because Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy were engaged in so many things: faking cables, the Ellsberg break-in, numerous other things that that one, if they started talking about, was going to lead - the whole house was going to come down.

Studs Terkel Now I'm thinking, also the feeling that you were feeling. You met, because we should perhaps even describe your meetings with Deep Throat. This man, this person you know.

Carl Berstein I think you're talking particularly about May 17th, 1973.

Studs Terkel When suddenly you realize that somebody might get hurt. I mean really hurt, or killed, such as--

Carl Berstein Well, what happened is that Bob had a meeting with Deep Throat that night, and he called me at the office and said, "Come over to my apartment right away." And I got there, and he put his hand over his lips to indicate silence, and he went and put on a a record - in this case, a Rachmaninoff concerto. He's got awful taste in music [laughter]. And--

Studs Terkel [unintelligible] [argue about that?].

Carl Berstein So turned it up real loud to make sure that if anything was bugged, that that nothing could be heard and then he took a piece of paper and wrote a little note to me. And says "Deep Throat says everyone's life is in danger." And I said, you know, "what's going on? Has Deep Throat gone a little crazy this time or what?" And Woodward shakes his head, and then he sits down at the typewriter and proceeds to to do an itemized list of 17 topics that he and Deep Throat discussed that night. Basically, what those topics involve was the whole Watergate cover-up, what we've heard about in the last year about the president's alleged involvement, the Howard Hunt blackmail scheme, the attempt to blackmail the White House, executive clemency, offers to some of the now-accused conspirators of executive clemency. And it turns out that that 16 of those items on the list have all checked out, and the one that that we never had any basis for knowing was true was that everyone or anyone's life was in danger.

Bob Woodward It it tended to to symbolize that the notion that the stakes were increasing, that now there were serious allegations against the president of the United States, something that we we had a difficult time dealing with ourselves.

Studs Terkel Here's a question. Did you guys at any moment at that period feel scared yourselves?

Bob Woodward Sure, of of course. That night we felt very scared, and actually, Carl suggested that we've got to unload this information on somebody in a responsible position. So we we rousted Ben Bradlee, our editor, out of bed at three a.m. and went over to his house and held a conversation on his front lawn just because we were afraid--

Studs Terkel That the house might be bugged.

Carl Berstein We started inside the house. And Bradlee started to read this memo and he started to discuss it.

Carl Berstein And I, and I said, "Don't say anything." And he'd started to look around the living rooms as if he was, you know, like a stranger in his own house or something.

Studs Terkel So that was a, that, see-

Carl Berstein And the next day we met, in fact, with with the editors and other reporters on the roof garden at "The Post" because we were afraid the office was bugged.

Studs Terkel Yeah, so there's - it could be, it could not be true, it might be true. And also paranoia sets in here, too, which is quite justifiable. Or were you not paranoid at all?

Bob Woodward Well, I don't know. We we look back on it sort of, we were responding in a in a protective way to our our own position. Whether it was called for or not I just don't know.

Studs Terkel I'm thinking just, sorry about that.

Studs Terkel As you were meeting Deep Throat, you have certain - the book, by the way, was very dramatic and as the reality, the truth, how you met him, the arrangements and the underground garage that you sat there. Well, weren't, you know, there moments in taking cabs in different places and he meets you. It sounds as though you guys might have been knocked off very easily it would seem.

Bob Woodward Well well, there was, I mean, in that case a particular- particularly important to protect the person involved.

Carl Berstein To protect his identity. I think that's what we were more concerned about than than physical well-being at that point.

Bob Woodward It, it's interesting what - how we came to write this book sort of in - when as we were writing these stories we were pretty much convinced in the the fall of '72 that we'd got a corner on the White House secret operations and we had hints that there was much more there than we knew than just the Watergate burglary.

Carl Berstein And that there was an organized cover-up occurring.

Bob Woodward And so we contracted to write a book sort of a Howard Hunt/Gordon Liddy/John Mitchell book that where they went and what they did, which would be sort of a history. And we actually started to write such a book, three or four chapters. Then McCord's letter charging perjury in a in a cover-up was released in March of '73, and the the dam broke. And at that point it became clear that we were gonna have to - that to finish this book in the midst of of this story we were going to have to concentrate on our role.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Bob Woodward And, and we wrote the book. And one of the people who really helped us in this is our editor at Simon & Schuster, Alice Mayhew, because we didn't have much time. We were still working on the story and--

Studs Terkel I'm thinking of a very enthusiastic review by Gary Wills in the "New York Review of Books" in which he says, of course you guys were police reporters, crime reporters. You were investigating, in a sense, a Mafia, you know. And the language used, you were you were kind of, shaking my head, that the phrase "I'll drop it in the deep six." You know what deep six - as though it was guys in Chicago and Cicero talking, you know.

Carl Berstein Yeah, the language--

Carl Berstein Sometimes was was really stunning. And then by language I don't mean the the kind of language that we've heard in the presidential transcripts, which is to say the expletives. I think Woodward and I use them ourselves, and we do in the book for that matter. But rather the the the idea of the president and his closest aides speaking as conspirators.

Studs Terkel Yeah, this is the part--

Bob Woodward Saying "Joe, we're going to get caught on this. You better drop it in the river on the way home."

Studs Terkel So it's not accidental that two local reporters - and this is two metropolitan reporters rather than national reporters - did this.

Carl Berstein Well I think, I think in a sense that's what the book is really about. It's about Washington journalism and how it's practiced and how it's not practiced. John Mitchell - this gets back to to sort of the beginning, the point you made at the beginning of the show with the the learned professor there. John Mitchell said very early in this administration, "Watch what we do, not what we say."

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Carl Berstein Well, I think you can see that the Washington press corps, certainly for the better part of four years, concentrated on on watching what they said, not what they did. And and indeed maybe the press bears a measure of responsibility for the Watergate mentality in the sense that had we watched what was really going on, not what Ron Ziegler said--

Studs Terkel Perhaps we could end, even all we're doing here is just touching on the book "All the President's Men" with Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. This just, this conversation occurs not too long after the righteous indignation of Henry Kissinger on being, his veracity being questioned. And I thought immediately, of course, of Peter Sellers and Dr. Strangelove and the identical role-playing was fantastic; he would be great as Sellers, by the way. There's a scene here toward the end, we'll end with this, you know. Woodward is questioning Kissinger. The fact that you're questioning him in itself, you know. Do you want to read that?

Bob Woodward This is more than a year ago. The very issue that Kissinger threatened to resign over recently here, and that is the, the wiretaps on his own aides. And we'd obtained information from two FBI sources that, in fact, Kissinger was the initiator of this. It seemed like a relevant story because the wiretaps had just, the existence of them had just been recently disclosed and confirmed by the, by the FBI officially, and so I called him up to ask him about his role.

Carl Berstein And it should be noted, I guess this was in May of '73, and and it's almost a very, very similar to what's happened in the last 10 days with Dr. Kissinger in the same subject. He called Kissinger and he was rather incredulous, Bob was, at what he had learned from these two FBI sources. And he said that he reached Dr. Kissinger on the phone, and Kissinger said, "Hello." And Woodward explained that that reporters had information from two FBI sources that Kissinger had authorized taps on his own aides. "Kissinger paused, 'It could be Mr. Haldeman who authorized the taps,' he said. 'How about Kissinger?' Woodward asked. 'I don't believe it was true,' he stated. 'Is that a denial?' A pause. 'I frankly don't remember. He might have provided the FBI with the names of individuals who had seen or handled various documents had been, which had been leaked', Kissinger said. 'It is quite possible that the FBI construed this as an authorization. In possible individual cases, it is possible that I pointed out who handled what document to my deputy who, in turn, would have passed on the information to the FBI.' Woodward said that two sources had specified that Kissinger had personally authorized the taps. A brief pause. 'Almost never,' Kissinger said. Woodward suggested that 'almost never' meant 'sometimes.' Was Kissinger then confirming the story? Kissinger raised his voice angrily. 'I don't have to submit to police interrogation about this,' he said. Calming down, he went on, 'If it is possible and if it happened, then I have to take responsibility for it. I'm responsible for this office.' 'Did you do it?' Woodward asked. 'You aren't quoting me? Kissinger asked. Sure he was, Woodward said. 'What?' Kissinger shouted. 'I'm telling you what I said was for background.'" And here we should interject, I guess, that background means that, that the official, in this case Kissinger, is not to be quoted by name and it's to appear as if it sort of came out of thin air. "Woodward said that they had made no such agreement about background. Quote, 'I've tried to be honest, and now you're going to penalize me,' Kissinger said. 'No penalty intended,' Woodward said, but he could not accept retroactive background. 'In five years in Washington,' Kissinger said sharply, 'I've never been trapped into talking like this.' Woodward wondered what kind of treatment Kissinger was accustomed to getting from reporters." And I think that in a way is, is really what this story is all about; the kind of treatment that the administration was accustomed to getting from reporters.

Studs Terkel This is what the book's about, too, and you know, I know that there's so much we can talk about; it's just touched upon this really just. The book "All the President's Men" dealing with an open society, how long will it be open. And it's open now, thanks in no small, no small degree to the work of investigative journalism. Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, "All the President's Men". Thank you very much.