Labor & Work by Ellie Shermer

Today, most Americans have a pretty narrow definition of the labor movement and what it means to be working class. If you ask, they might mention steelworkers, miners, and construction workers, which implicitly presumes that only white men (generally assumed to be conservative) were and are the only ones to be found in the country’s blue-collar jobs and trade unions. Studs certainly talked to his share of steelworkers and miners. He even interviewed truckers, like Paul Dietsch, who had no interest in joining unions, disdained government regulations, and loved open roads as much as free enterprise.

Yet the interviews with workers, union leaders, and experts in the Studs Terkel Radio Archive give a far different and more accurate sense of what it has been and is like to work, organize, and live in America. Studs constantly lamented during many of these interviews that many citizens, particularly young people, don't know this history or really grasped how things were changing. As in his most famous book, Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1974), Terkel introduced listeners to the many folks struggling to get by. Striking nurses, former prostitutes, militant farmworkers, immigrant laborers, independent truckers, anti-war unionists, public-sector employees, and unemployment experts routinely explained how things had changed, often for the worst, for them and their families in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. But these outspoken Americans also made clear what they endeavored to do in order to make the country even greater than it had once been.

Studs’ recordings exemplify how he always understood how the American workforce and labor movement had begun to shift in these pivotal decades. The headlining-grabbing unions in the 1930s and 1940s had been in the auto, electronics, and steel industries, whose workforces had used newfound workplace rights to bargain for the better wages, benefits, and working conditions that improved living standards at home in the 1940s and 1950s. But, by the 1960s, those jobs had started to disappear, either as employers started businesses elsewhere or more likely automated existing plants so that one person did the job of several. The wages and benefits for the remaining work also declined, even though the labor was still backbreaking, as thirty-five-year-old steelworker Ed Sadlowski explained. That native Chicagoan made quite clear to Studs that working conditions were deteriorating but had never been luxurious or even a real gateway into the middle class. Few kids in his neighborhood had thought college possible. They did what Sadlowski did, graduate high school and head to the steelyards where good work proved increasingly hard to find.

That decline had been but one reason that Sadlowski challenged the leadership of the United Steelworkers of America in 1974. He detested the aging leaderships’ support for the Vietnam War, in which a disproportionate number of working-class Americans fought. He also considered the union to have become increasingly undemocratic, a sentiment that won over a sizeable number of young, old, white, Black, Latino, male, and female steelworkers who wanted more say on the job and in their union. That demand also inspired their families who, as Sadlowski’s wife Marlene told Studs, also took part in the successful campaign to make this young, dissident unionist the union’s director for the important area stretching from Chicago to Gary, Indiana.

That kind of militancy could also be found amongst service workers, nurses, and government employees, who would make up the majority of the American labor force and labor movement by the century’s end. Many of these workers noted that they had not prospered as much as manufacturing and heavy-industry workers had after World War II. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) organizer Jerry Wurf clarified that government workers had been purposefully excluded from the 1935 Wagner Act, which had guaranteed federal and therefore employer recognition of unions that employees formed. As such, public jobs, ranging from garbage collection to teaching, had remained poorly paid, often unsafe, and largely unorganized.

Wurf celebrated the gains that public employees had made since the 1960s. Roughly 1,500 a week joined AFSCME when Wurf talked to Studs in 1974. Members were also extraordinarily diverse and doing the kind of white-collar jobs, like secretarial work, that many Americans still don’t realize have been unionized. Continued ignorance frustrated Wurf who swelled with pride when he described the diversity of AFSCME’s steadily increasing membership.

He could also have talked about the militancy of trade the union movement’s new faces, like striking Ohio nurses Mary Runyon and Kathy Ann Keller, whom Studs interviewed in 1982. Unlike Marlene Sadlowski and other Steelworker wives, these women did more than just stand behind men demanding better wages and working conditions. Runyon and Keller instead had the support of each other and their husbands as they led a yearlong strike for raises, benefits, and shorter hours, which eased the strain on staff and better serve patients.

United Farmworker organizer Dolores Huerta also emphasized what a difference organizing has and continues to make in the lives of every citizen, not just workers and their immediate families. Studs interviewed her in 1975 when she and her brother-in-law Cesar Chavez had already inspired many Americans to boycott grapes in order to force California growers to recognize the largely Latino/a union. Huerta spoke movingly about the plight of agricultural workers, who, like public employees, had been left out of the Wagner Act. Pickers often moved themselves and their families from harvest to harvest. Children often went to several different schools in any given year and even had to skip class if an employer forced parents to bring their children to pick fruit alongside them in fields, where they lacked water, food, and toilets. Huerta pointed out that those unsanitary conditions harmed both workers and consumers, all of whom benefited from the higher wages, better hours, and improved working conditions that farmworkers had begun to negotiate in historic contracts with growers. Some families now earned enough money to buy modest homes and give their children the kind of stability to help them finish school.

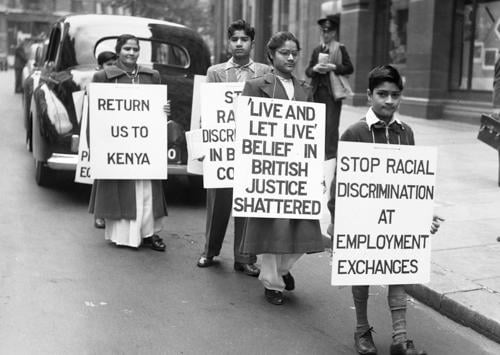

Studs also handed over his microphone to historians, social scientists, and fellow journalists who recounted how widespread such inequality remained in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. For example, famous, by-then Midwestern-based, social work expert Henry Ollendorf emphasized that Turks in Berlin and Algerians in Paris both found themselves confined to low-paying work that native-born Germans and Parisians would no longer do. Those new arrivals, like the Puerto Ricans Studs interviewed at a northside Chicago jobs project, had little hope of finding a better life at home or in a rapidly deindustrializing Western Europe or United States, where native born populations depended on them for cheap labor but had no interest in extending full citizenship rights to them. The British whom Studs interviewed in 1962 were no exception. Many in that Midlands pubs described growing up in poverty in the 1930s and 1940s, faring better in the 1950s, but still recognized (as Sadlowski had) that more money had done little to erase longstanding class divides.

The persistent inequality, struggle, and diversity to be found amongst everyday people is perhaps the most startling aspect of Studs’ interviews with workers, activists, and experts. As such, these stories serve as a reminder as to how varied, vibrant, and interconnected America and the rest of the world has always been and why that diversity, adversity, and common cause, as Studs always emphasized to listeners, needs to be remembered.