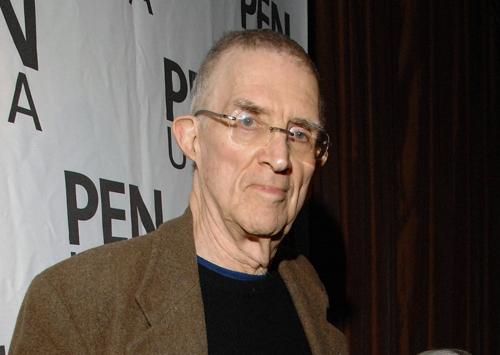

Interview with Ian Wallace

BROADCAST: Nov. 16, 1962 | DURATION: 00:30:53

Synopsis

British baritone Ian Wallace discusses Glyndebourne Festival Opera. Recorded while Studs was in England.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Ian Wallace So he took all this in and one morning Audrey was awakened by the sounds of workmen and spades hitting on stone and so on and she said, What on earth's going on? And he said, They're digging the foundations of the Opera House. This was a great shock and a surprise to her. So it was built. He was an extraordinary man.

Studs Terkel This was what year?

Ian Wallace This was when around 1933.

Studs Terkel Thirty-three.

Ian Wallace He decided that that was a time, Britain had gone off the gold standard. We had had the first of the depression in '29, '31, that period and he took the quite logical viewpoint that depressions were the time to start big things because if you waited until you could afford them you never would afford them. So the time to start was when things look black. That was one of many many courageous decisions that he took. They built the Opera House and friends said this is a white elephant. In fact one friend of Mr. Christie's who was an amateur singer got up on the stage one day when he was taken in to show the almost completed building and he sang a few phrases of I think a Debussy or a Faure song and he said, Well John that is the first and last time that anybody will give a performance on this stage. Well the next thing they had to think of was who would be a suitable musical director, who would be a suitable producer. And the first names that were thought off were Toscanini and Max Reinhardt. This was aiming--

Studs Terkel [Oy?]

Ian Wallace At the stars really.

Studs Terkel The man of music and the man at the theater.

Ian Wallace Exactly. Well not surprisingly this was not possible. And so they found Fritz Busch and Carl Ebert and they asked these two very distinguished as they were then, young, or comparatively young men of the theater and of music, to come over to Glyndebourne and have a look. Now perhaps I should tell your listeners where this unlikely place for a great opera is. It lies roughly 60 miles south of London; not a particularly easy road certainly not by American standards. It takes from the center of town under heavy traffic conditions at least two hours of pretty difficult driving. You have the heavy traffic of south London to get through and then you have a road to the coast of one of our seaside resorts called Eastbourne and it's not a wide or easy road at all so that you have by car a not easy journey. To get to by train it is just under an hour's journey from Victoria Station to Lewes the old county town of Sussex where the assizes are. And from there it is three miles by bus or taxi. So it's, there has to be something pretty good at the end of a journey [unintelligible]--

Ian Wallace To draw people there. Now these two distinguished men arrived to see the theatre and to talk to this what they knew as a wealthy English landowner whom they had heard was something of an unconventional man--

Studs Terkel Wanted to be a patron of the arts.

Ian Wallace Exactly.

Studs Terkel But they heard he was somewhat eccentric.

Ian Wallace Somewhat eccentric and absolutely the antithesis of of a man of arts certainly. Ebert had been a leading actor in theatres in Berlin, played parts as dramatic as King Lear, Shakespearean roles, dramatic roles in modern German drama, and had that time recently forsaken the stage to produce opera in Berlin because he was very much a believer that opera suffered from very bad production. The status of the opera producer in those days was simply somebody who said to the great prima donna, Madam would you care to stand here for this, and would you care to stand there, and the chorus might be grouped a little bit and they were asked to do meaningless gestures and that was about as far as [unintelligible]--

Studs Terkel There was no staging.

Ian Wallace There was no staging.

Studs Terkel There was no direction at all.

Ian Wallace They were really, in those days operas tended to be sung concerts in costume.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Ian Wallace Fritz Busch ever was of course an Austrian musician of the highest caliber and with a particular love for Mozart and for Mozart opera. So it was a formidable combination. They came over they, heard what John had to say, they had a look at this tiny opera house. It's been over the years much enlarged but in those days the seating capacity I think was around 400. I wouldn't like to be too certain about that but there or thereabouts, and they said, Well it's a marvelous idea but you must forget all about it. This is uneconomic. This is impossible. This is something that, we hate to think that you're going to lose all the money that must inevitably be lost in a project of this kind. And he roared with laughter at them and said well you can say what you like. I'm going ahead. And they said, Well you you must be mad. He said, I am mad, that otherwise probably I would do it.

Studs Terkel He had this, he had this fixed idea.

Ian Wallace There was a vision here and he had at his side Audrey who was by this time equally infected with his enthusiasm so he persuaded these two men to do it. And they assembled a cost for the first season in 1934, a very short season about half a dozen performances of two operas, "Marriage of Figaro" and "Cosi." The casts were made up of distinguished artists from the continent and British artists who were at that time tried and true. And in both operas Audrey Cristie appeared. She had a voice that perhaps would not by the standards of the immortals be regarded as anything tremendously outstanding. It was, but it was very very good. And she was an artist: as an actress, in her appearance, and her feeling for the work, of the very highest order. Well, it was very, this is where the story becomes almost a fairy tale. These people arrive. They were not paid a lot of money; there was not a lot of money to pay artists. But it must be remembered at that time 30 years ago opera singers in the summer were unemployed. Opera seasons were things that happened in the winter. And this was a wonderful thing for them to be able to have work and they weren't too worried about how much they were going to get to do it. The first performance seven people just seven. [Unintelligible].

Studs Terkel A house of seven people

Ian Wallace Well it wasn't quite a house of seven people because there were a number of friends and relations in the district who came, but only seven people came from London.

Studs Terkel Seven from London.

Ian Wallace They seven got onto this special train at Victoria and traveled down. But fortunately two of them were the music critics of the "Times" and "The Daily Telegraph," and what they had to say next day was exciting. One of them said Let it be clearly noted that there was a performance last night of Mozart opera such as has not been seen in this country before.

Studs Terkel Oh, that's marvelous.

Ian Wallace The words are not exact--

Studs Terkel Yeah, but that's the idea.

Ian Wallace But that was the message. And a great deal more he had to say like it and his colleague from the other paper agreed with him 100 percent. The second night there were also around seven people. But that was the last time that that train went off without its full load. And it's been a remarkable story because since those days Glyndebourne has played virtually to capacity at every performance. Now why was this? It was because apart from the artists being carefully chosen you had a preparation for an opera such as is normally impossible. There was, and there still is, a rehearsal period for a production, a new production at Glyndebourne, lasting five solid weeks and it is--

Studs Terkel I mean it's a five week rehearsal period for let's say for "Don Giovanni" or "Marriage of Figaro"?

Ian Wallace Yes.

Studs Terkel It's a five week rehearsal period.

Ian Wallace A five week rehearsal.

Studs Terkel Like Moscow Art Theatre might do it [in a way?]

Ian Wallace Exactly. Now in addition to there being a five week rehearsal period, every Glyndebourne contract has always had written into it the little remark, "Artists will arrive music and word perfect for the first rehearsal."

Ian Wallace So that Glyndebourne are not concerned with donkey work. They, rehearsal is polishing and--

Studs Terkel Subtleties and nuances all this is part of it.

Studs Terkel Not a question of memorizing lines.

Ian Wallace No no. This you are expected to arrive with.

Studs Terkel And thus character comes into being.

Ian Wallace Exactly. To go back to the beginning, the very first manager at Guy born was a Mr. Nightingale. He was, had been I think an orchestral manager before he came to Glyndebourne and this was a splendid start. But before long there came on onto the scene as general manager a man who is well known to you in America, Rudolf Bing, now manager of the Metropolitan.

Studs Terkel I didn't realize--this is my own illiteracy and this matter--I didn't realize that Rudolf Bing was a general manager of Glyndebourne.

Ian Wallace Rudy Bing as we call him, was general manager from I think the second year, second or third year, up until after the war. Of course it all stopped during the war; Glyndebourne became a home for evacuated children, the sort of typical gesture of English people with the resources of the Christies is to throw everything that they've got in wartime into something more important at that time. Up to, up to the war, Glyndebourne was was largely a Mozart house. Not entirely. Performances were given of Donizetti's "Don Pasquale," with a cast including the great Mariano Stabile, Dino Borgioli, Mrs. Christie, and Heddle Nash our English tenor who also alas died matter of about a year ago. And Verdi's "Macbeth" was also done before the war with the fabulous Margherita Grandi singing Lady Macbeth. The thing developed in those pre-war years and I think perhaps having told your listeners how the public leave Victoria Station or by car, what apart from this fabulous preparation for the operas did they find when they got there? They found a beautiful country house standing in its own grounds with a lake with waterlilies on it. Views of the Sussex Downs. These are green, low hills, very gentle in their slopes but they conceal the sea, the English Channel, which lies just ten miles beyond. A lovely English rural setting and the performance from the beginning of Glydnebourne and still to this day takes this pattern that it starts early. It starts usually around quarter to six, maybe quarter past at the latest according to the length of the work to be performed, and halfway through the evening there is what we call the long interval. The long interval is 75 minutes and in that 75 minutes the public adjourn to the restaurant where there is served a beautiful dinner and a wine list that has as much subtle blending as the ensembles that--

Studs Terkel Oh, that's marvelous.

Ian Wallace They're going to hear inside the theater. So that from an artist's point of view the second half, particularly if the opera is comic, tends to go rather better even than the first half.

Studs Terkel With a bit of inspiration.

Ian Wallace A little bit of inspiration. And they have a walking garden.

Ian Wallace And--

Studs Terkel It begins early. Because of this it begins early.

Studs Terkel So Londoner's take a pretty early train?

Ian Wallace Yes. In fact there is another little added quirk to this, and so far that Mr. Christie always believed that the public would enjoy themselves more if they dressed for the opera. And on all the publicity for Glyndebourne with your tickets and so on you will find the phrase, "evening dress is recommended."

Studs Terkel Aah.

Ian Wallace Now recommended really means, meant in Mr. Christie's idea, obligatory. This, if something--

Studs Terkel It's a euphemism then, for oh,--

Ian Wallace A little bit yes. If anybody turns up not in evening dress they will not be excluded. For example many Americans coming to this country and wanting to go to Glyndebourne may not have brought their tuxedo with them.

Studs Terkel Not even aware of it.

Ian Wallace They will come in say a dark suit. This is perfectly acceptable. I've known people arrive at the Glyndebourne in a pair of shorts and with a rucksack on their back and they'll say, Well we have hitchhiked here from Denver, Colorado.

Studs Terkel Probably some of the young kids who love this music--

Ian Wallace Yes.

Studs Terkel [Unintelligible] work.

Ian Wallace And it's, I've known Mr. Christie say, Well I'm terribly sorry. Every seat is gone but if you would care to come and sit in my box with me and--

Studs Terkel Really?

Ian Wallace Maybe they find themselves sitting next to the Bishop of Chichester or somebody!

Studs Terkel This with John Christie then.

Ian Wallace Oh an immensely approachable man. A man of, with a most dignified appearance. Not, in his latter years, not unlike Winston Churchill in appearance. This is slightly deceptive but the same bulldog breed look about him; a very prominent--

Studs Terkel It's a good description.

Ian Wallace Chin. Twinkling blue eyes, balding with white hair.

Studs Terkel Tufts.

Ian Wallace Little sort of tufts. In his last year of life when he was nearly blind he decided that shaving and hair cutting was something that was wearisome,--

Studs Terkel Unnecessary.

Ian Wallace And he was a very sick man. And in the last season he grew a long white beard and let his hair grow as well and he changed from a Winston Churchill type to becoming a Biblical prophet.

Studs Terkel A Biblical prophet.

Ian Wallace Elijah [is the nearest thing?] [unintelligible].

Studs Terkel Well this is a very graphic picture that your painting, and while it's of Glyndebourne and the man who, the guiding spirit behind it. He wanted the evening then to be a full rich one in every way. That is a love of life--

Ian Wallace Oh yes. And he another--

Studs Terkel [Unintelligible] of love of the music.

Ian Wallace He had another point too about the public dressing and that was, he said the artists have taken an immense trouble over this work and it is a mark of respect to them that you should take the trouble to dress up a little. And it's now in the summer quite a part of the English scene to see men and women in evening dress getting onto a train at Victoria at twenty to four in the afternoon. Nobody gives this a second glance anymore.

Studs Terkel They know where they're going.

Ian Wallace They know where they're going.

Studs Terkel Glyndebourne bound.

That's the Glyndebourne people.

Studs Terkel And the story of Glyndebourne, this one you tell is a very moving one and a fascinating one. Of course and we hear, we have recordings, albums, [two I know?]. The station of course [found? sponsored?] John Brownlee doing Giovanni.

Studs Terkel As Don Giovanni in "The Marriage of Figaro" at Glyndebourne. Albums [unintelligible].

Studs Terkel Yes.

Studs Terkel I know there're a great deal more. But as you're telling this story, Ian Wallace, I think you reveal something about yourself too. You too, obviously it's your own love and feeling for this idea, this concept of opera, and your respect for the man who founded it. We should know something of Ian Wallace, you haven't said anything about yourself and I think this is rather interesting. Here's an artist--

Ian Wallace Well--

Studs Terkel [Taken with the idea?]

Ian Wallace In a way I can take up the story. We've taken it to some extent up to the war now; I joined Glyndebourne in 1948. I had had a curious career in a sense because I was trained for the law not as a singer or an actor at all. I'd been taking part in amateur theatricals from the age of five, but it had always been a sideline. I went up to Cambridge University after school to study law and the war broke out and I went into the army and that was that. I lay for two years on my back; during the war I had a motorbike accident in the army and got a diseased bone in the spine and that two years was valuable in a way because it gave me a lot of time to think. And I decided that although my father was very keen on the idea I should be a barrister as we call him over here, I never had really felt this was for me.

Studs Terkel Neither did I. I studied law too. It was a great mistake.

Ian Wallace Oh really? Yes, yes. Mind you, it does help you to look at the small writing on the contracts with--

Studs Terkel I'm terrible at that anyway.

Ian Wallace I'm not very good at it either. And so I decided that I must give my first love, which was the stage, a try after the war and I began as an actor. I never thought my voice was good enough for opera and I thought it might do me alright in musicals but not for opera. But I was persuaded to give auditions and to my astonishment I was accepted as an opera singer, and the company that I worked with in London had the great good fortune to, from my point of view, to engage Carl Ebert, who was the Glyndebourne producer before the war, as their producer, and I took his eye and when he returned to Glyndebourne in 1948 he asked me to sing the part of Masetto in "Don Giovanni" which was not being performed at Glyndbourne but at Edinburgh Festival. This was the second of the international festivals at Glyndebourne and I might say that it was the inspiration of Audrey Cristie again who started the Edinburgh Festival. She thought this would be a wonderful idea and indeed the Glyndebourne administration--

Studs Terkel I didn't realize that. So the Glyndebourne administration--

Studs Terkel Particularly Audrey Christie, was responsible for the Edinburgh Festival.

Ian Wallace Yes, took, it was her idea and it was put up to the city fathers of Edinburgh who were most co-operative and far seeing people in those days. And Rudy Bing was appointed as the first director of the Edinburgh Festival. So Glyndebourne had a hand in that. They no longer have anything to do with the administration but in those days they did. And so Ebert kindly took me to Glyndebourne and it was, this is how I can speak with some authority about the preparation for the opera house because I worked with Ebert and this, this was a great man. He paid singers is the compliment of assuming that they could act even if they had never acted in their lives before. And he's an old fashioned producer in this respect that he showed actors, singers rather, what he wanted. He gave the performance. One minute he could play the part of one person on the stage. Then he could switch in a second and play the other. And one watched this and one said to oneself, Well I could never never never do that. But at least I can try. And although one's try was nothing like his execution, at least one one got somewhere and he would stand--many a time I've been singing an aria, doing a bit--and he would stand in front of me and almost like Svengali would would will do one to do, he would he would be doing the expressions with his face.

Studs Terkel I can see the scene as you're doing it now.

Ian Wallace And he was not a man who suffered fools gladly. Many a time he would shout, he would tear his hair. One always knew when trouble was coming when he ran his fingers through his wonderful head of silvery white hair and a tortured expression would come on his face and you knew that any moment the explosion would come to redouble your efforts and maybe you averted that crisis.

Studs Terkel But he made actors out of not-acting singers in some cases?

Ian Wallace He indeed. And the other basis of the great success at Glyndebourne was the the attention to the ensemble singing. There were no stars and are no stars at Glyndebourne. We have had Sutherland singing there. We've had [name of opera singer]. Many other famous people. But at Glyndebourne we work as a team and everybody who comes to Glyndebourne as a singer for the first time is a little scared. Now this is a very good thing. An artist may come as a great star in their own country but when they come to Glyndebourne they know that more is expected of them and they are expected to work one with another. When your solo comes out in the ensemble everybody else is quieter when it's somebody else's turn. They come up and so on.

Studs Terkel Real ensemble acting and singing.

Ian Wallace That is, that is it. Backed by magnificent decor. People like Oliver Messel, Hugh Casson, Zeffirelli. All the whole thing works as a team. This this is it's--

Studs Terkel Again this is interesting. Again Ian Wallace wandered from himself back to Glynde--Which I think is revealing of you to a great extent. You yourself, we know you as a, I guess a bass baritone buffo.

Ian Wallace Yes.

Studs Terkel You specialize in the comic roles, Don Bartolo--

Ian Wallace Yes.

Studs Terkel Poor Masetto who has a rough time--

Ian Wallace And I think my favorite Don Magnifico in Rossini's "Cenerentola." Well it's, to talk about myself for a moment, it's some indication of what Glyndebourne can do for an artist that I have as a Scot coming in with any tremendous training, after some years at Glyndebourne was invited to sing "Cenerentola," Don Magnifico, at the Opera House Rome, to sing [Doctor?] Bartolo at the Fenice in Venice, to do HMV international recordings and one of our most exciting times was when we went back in 1954 with Ebert who had just been reappointed to be the [General-Intendant?] of the West Berlin Opera House. He'd spent a lot of time as a professor of opera in California and he's now retired to California. He went back and he thought the best thing he could do to open his first new season at Berlin was to fly over the Glyndebourne production of "Cenerentola," our most exciting night. Alas he wasn't able to be there himself, he got very bad bout of influenza and he was in bed but the news was carried to him that we took 36 curtains at the end to the opera.

Studs Terkel Thirty-six. Wow. See what's interesting too Ian as you're talking to me, you are talking like an ensemble man. That is, you are an individual. Obviously you are Ian Wallace and no one else. But at the same time you've been so imbued with the Glyndebourne concept of the whole production that here you speak of that rather than--

Ian Wallace Yes--

Studs Terkel [Unintelligible], matter of fact.

Ian Wallace Maybe I do but it also gives one great confidence to be an individual when one is elsewhere. I've had other wonderful experiences. I played the part that Ezio Pinza played in New York in "Fanny" when we did "Fanny" at Drury Lane years, some years ago.

Studs Terkel You did the Cesar?

Ian Wallace Cesar, yes. And I've done a review over here. I even do variety performances--

Studs Terkel I think we should point out that you're, aside from being a performer of serious music, opera and musical comedy too, you do comic songs, Donald Swann of Flanders and Swann written songs for you and I hope we hear them soon on WFMT, your own private zoo!

Ian Wallace Oh well I hope so too. Michael and Donald of course who are great personal friends of mine did a great, dod me a great favor because there's a there's a comedian in here that's always bursting to get out. And I--

Ian Wallace In me. Oh yes. And I always wanted to sing comic songs. But when you're an opera singer those comic songs have got to be, to have a certain musical content otherwise your operatic public are outraged. And Donald and Michael provided just that: songs that had good lyrics, sophisticated lyrics, and a musical content that was--

Studs Terkel I think we should watch for, it's a Parlophone, Parlophone label. I think there's an American label to it too. It's called what, "Ian Wallace's Private Zoo"?

Ian Wallace "Ian Wallace's Priva-- Well, "Wallace's Private Zoo."

Studs Terkel Wallace's. And it's "Mud, Mud, Glorious" [sic], is that "The Hippopotamus Song"?

Ian Wallace That is "The Hippopotamus."

Studs Terkel And we [could?] hear you doing the hippopotamus and other members of your own bestiary.

Ian Wallace Yes.

Studs Terkel Ian Wallace, you're a Scot, perhaps, I noticed our time was just gone because the story you tell is a fascinating one. I look at a BBC clock up here, and it's directly ahead of me, and I should point too that Penny, who is very delightful behind the [glass and chrome?] is our, we use the phrase engineer but I think she is in charge of--

Ian Wallace She's a studio manager.

Ian Wallace Yes.

Studs Terkel It has an impressive--

Ian Wallace Oh very. Yes. Well she looks very impressive.

Studs Terkel Yes indeed. And Ian Wallace, I thank you very much for this, for this portrait you've painted both of a very unique organization that certainly will go on, continue with with the spirit of Christie, Glyndebourne itself. And a picture of you in a very, your own way, it came out. I hope someday we can see you and hear you in America.