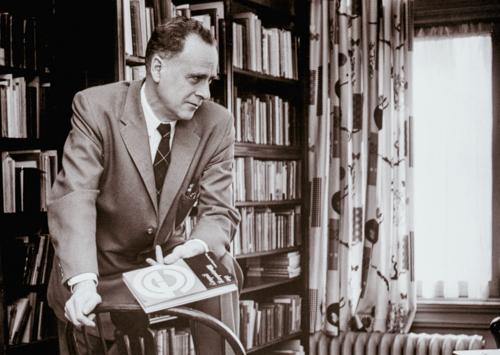

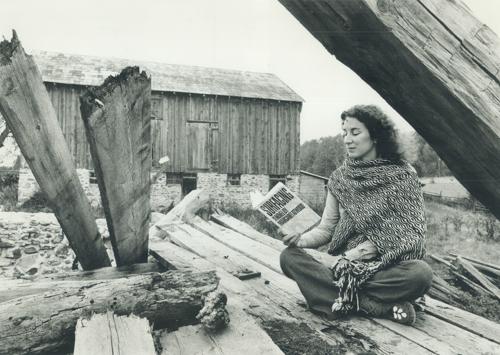

Barbara Branden discusses "The Passion of Ayn Rand"

BROADCAST: Aug. 26, 1986 | DURATION: 00:50:53

Synopsis

Discussing "The Passion of Ayn Rand" (published by Doubleday) with the author Barbara Branden.

Transcript

Tap within the transcript to jump to that part of the audio.

Barbara Branden [reading] "Ayn Rand was led to define two different ways of facing life. Two antagonists. Two types of men: The man of self-sufficient ego, of first-hand, independent judgment, the man whose convictions, values, and purposes are the product of his own mind -- and the parasite who is molded and directed by other men. The man who lives for his own sake, and the collectivist of the spirit who places others above self. The prime mover whose source of movement is within his own spirit, and the soulless being who is movement without an internal mover. The creator and the second-hander. The culture has changed since the '40s, in significant part, as a result of the works of Ayn Rand. Her ideas have spread, they have been heard, they have made a difference. The book and reality are working."

Studs Terkel Those are two, I think, very telling sequences in the book, the biography of Ayn Rand, author of "The Fountainhead" and "Atlas Shrugged", among other works, by someone who's very close to her down through the years, Barbara Branden, published by Doubleday. And I'm thinking of Ayn Rand, and especially those two books, and her effect upon the young, and the change in the way we think today, a great many of us do. The first part you read, Mrs. Branden, that part about two kinds of people in the world--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel One kind that's self-sufficient, out for self, by God,

Barbara Branden Yes indeed. Without sacrificing the rights of other people--

Studs Terkel

Barbara Branden Mhmm. --but out for self, yes.

Studs Terkel Out for self. As against--

Barbara Branden What Ayn called "the collectivist of the spirit" whose values are formed because they're the values of others, whose goals are chosen because they're the goals of other people, who doesn't set his own purposes.

Studs Terkel Even though, I think--once called the outer-directed person against the inner-directed person, something

Barbara Branden Ayn would not use those terms, because--

Studs Terkel That was Riesman, a guy named

Barbara Branden Yes, that's right.

Studs Terkel But you wouldn't use those terms.

Barbara Branden No. No, they wouldn't quite fit.

Studs Terkel But you're saying--the, uh--the one, the collectivist of the soul who places others above self--

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel She was against that.

Barbara Branden She was passionately

Barbara Branden She thought it was--it was very dangerous and very bad in a man's soul. It made him a robot, pushed and pulled by others. And, in politics, it made him accept dictatorship, the rule of others, whatever. It made him--it made him an acceptor, not an initiator.

Studs Terkel Placing others above--so someone like, I suppose, Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King would not rate too high in her book.

Barbara Branden No, no. They would not. Mahatma Gandhi?

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden No. No, that would be, to her, the model of the altruist, whose life was sacrificed to others--and who was not above telling others what to do, which is usually the case.

Studs Terkel That's interesting. There's nothing adorned in this thing. It's direct, straight. This is it.

Barbara Branden She said it straight. And the chips fell where they fell. And there was a lot of antagonism to many of her ideas because she never pussyfooted about them.

Studs Terkel And so, see--what fascinates me about this--[unintelligible] now years later, today, many of the young are followers of Ayn Rand's philosophy of self above all -- you, the person -- who call it "the me decade" or whatever they want to call it.

Barbara Branden It's not quite "the me decade," and Ayn would not have liked a lot of what that stands for. Because she was very clear on something: She did not believe you live by whim or emotion. You don't just, if you feel like doing something, then you go do it and that's all that matters. Ayn was first and foremost a rationalist. She believed that whatever goals you chose, you had to rationally justify. That you didn't just decide "well, being cruel to people makes me happy, so my happiness is important, I'll do it." You had to have a rational justification, for your actions and for your purposes.

Studs Terkel I'm thinking that--rational justification of so many of the young today are out making it, and making it big.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel You know, and, in a way, devil take the hindmost--make it big, you know.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Ayn Rand disciple. I mean, she's had an effect on them.

Barbara Branden She's had a profound effect on our whole culture. I did a fair amount of research on that [match being lit] and discovered finally that there was--there was a book to be written there. It was a fa- It's a fascinating story. She began writing--her first novel was published in the '30s. It was an anti-communist book published in the Red Decade. She did not make

Studs Terkel a The Red Decade, you say.

Barbara Branden Of the '30s. It's been called the Red Decade.

Studs Terkel Oh, the Red Decade. Why? Because of the New Deal and--

Barbara Branden Because of the love affair with Soviet Russia, the noble experiment. Uh--and so--she was in trouble then. "The Fountainhead", which is a hymn to the individual, was published in the '40s. Then "Atlas Shrugged", which is a hymn to the--to the genius, to the men of accomplishment, to the men of the mind, as she called them, was in the late '50s. Throughout all this, her influence has been growing and growing and growing. It's--originally it was very underground. One didn't see it publicly, and one didn't normally see it in public people. Today that's no longer so. Everywhere I looked I found prominent people, not necessarily accepting all of her ideas, but deeply influenced by many of them. And in colleges, if they were professors, teaching some aspect of her ideas. Putting them into practice in their lives, in whatever field they worked in.

Studs Terkel Yeah, in fact, in this very administration--

Barbara Branden Yes, yes indeed. Alan Greenspan has been very influenced

Studs Terkel One of the economic advisers to--

Studs Terkel --President Reagan.

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel He's an Ayn Rand disciple.

Barbara Branden No, he's not--he--I wouldn't call him an Ayn Rand disciple. He was influenced by her.

Barbara Branden And agrees with many of her ideas, and certainly in the field of economics.

Studs Terkel And some of the Reagan speechwriters.

Barbara Branden That's right. Yes. Someone of- There isn't a field where you will not find prominent people influenced by her. Certainly including philosophy.

Studs Terkel Yeah. And among the philosophers too. Hayek and others.

Barbara Branden Yes, yes. Who admire her work. Yes

Studs Terkel And, and- By the way, we always talk of universities as, you know, for years, we think of universities as centers of radical thought.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel That is, of left thought, subversion. You're pointing out that many of the teachers at universities are Ayn Rand

Barbara Branden Yes, that--well, in that sense, the universities are still the centers of radical thought.

Barbara Branden Because Ayn was considered very radical, although not to the

Studs Terkel left. [unintelligible]

Barbara Branden Yes. She was the one voice of protest against the left.

Studs Terkel Mmm.

Barbara Branden When I went to UCLA, when I first met her, and I was the campus pariah. Because I was arguing--I think with more heat than light--pro-free enterprise, and found that people were not talking to me. I mean, this was considered next door to an obscenity in those days. Today it's quite acceptable.

Studs Terkel When you say free enterprise, the entrepreneurial spirit you're talking about.

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel That's one of the things--when Ayn Rand testified as a friendly witness for the House Un-American Activities Committee against subversion in movie scripts, against--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --communism hidden in the scripts. Did she have evidence of that? Cases of that?

Barbara Branden Oh yes, she did indeed.

Barbara Branden She was extremely upset that she was not allowed to testify as she had been told she could testify. She was not interested in citing chapter and verse about what line of propaganda was in what movie. What she wanted to do was talk about how one recognizes propaganda in movies, what form it tends to take. For instance: If, for a period of time one doesn't see a movie in which there's a businessman who is anything but a villain, notice that. Watch. Maybe you're being--something is being communicated to you. Uh, issues like that. They had promised that they would give her a--the Committee had promised they would give her time to testify about it, and they didn't. She was very upset and felt the whole thing, for her, was a complete waste of time.

Studs Terkel She was watching certain movies where the businessman was considered someone

Barbara Branden That was one of the issues.

Studs Terkel --ethical. Yeah.

Barbara Branden Where profit-making was presented as sinful, giving away everything was good.

Studs Terkel What were some examples that she cited?

Barbara Branden There was a movie, oh dear--"The Best Years of Their Lives" was one

Studs Terkel "Best Years of Our Lives"?

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel That was a subversive film,

Barbara Branden No, no, no. She didn't--she didn't consider it subversive, no.

Studs Terkel But that was a film that did what?

Barbara Branden I mean--she didn't--by the way, she did not think anyone should go to jail or be prohibited from making any movies they wanted. She thought only that the American public, if they're going to accept certain ideas, should know that they're accepting them.

Studs Terkel Ah.

Barbara Branden Should recognize them. That--they're free, obviously, to accept whatever they want. But let them know what it is. Let it not happen by osmosis.

Studs Terkel "Best Years of Our Lives", I remember, it was a very popular--

Studs Terkel --with Fredric March and Myrna Loy, as I recall--

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel --and Harold Russell, the--you know, the armless vet. Uh, what was it in that film that she

Barbara Branden As I remember, that the banker decides, ultimately, that morality requires that he give loans to the poor without collateral. And that was virtue. I mean, that also breaks banks and destroys all the other depositors--but that was ignored. Virtue is to give away. And in this case, it would be other people's money as well, because they would be destroyed.

Studs Terkel That's interesting, because Ayn Rand's--she's straight. There's no doubt about her.

Barbara Branden [laughter]

Studs Terkel She doesn't hide what her philos- or her feelings are.

Barbara Branden No,

Studs Terkel "By God, you've got it. Don't you dare worry about that person who's--has tough luck."

Barbara Branden No, no, she wouldn't say that, quite. Um- [laughter] I remember at a talk she gave at Yale once--there's a sense in which she would say that--but in a talk she gave at Yale, a very angry questioner said to her, "Okay, in your society who's going to look after the janitors?" And she said, "The janitors." So, yes, there was an extent to which she thought, certainly people should look after themselves.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden However, she was certainly not opposed to generosity. If there's someone one wants to help, someone one values and one wants to help, that was perfectly fine. Ah, what she objected to was involuntary help.

Studs Terkel Ah. So the idea of charity, fine.

Studs Terkel But not governmental role--like the New Deal, I suppose. The New Deal of the 30s was probably anathema to her.

Barbara Branden Yes, it was indeed. It was indeed.

Studs Terkel What was it about the New Deal

Barbara Branden Well, it was as close to statism as this country ever got. I mean, it was an attempt to have state control of the economy. The NRA--the state was to control business and industry. We were on our way in a direction, she considered, she had just escaped. She had come from communist Russia, and she did not want to see the first steps of that again.

Studs Terkel New Deal as a step toward--

Barbara Branden Yes. I mean, it's not that she thought they were all communists. She didn't. That wasn't

Barbara Branden Ayn was not seeing communists under every bed. That wasn't her style.

Barbara Branden Not even most. No, she was much more concerned with the philosophical underpinnings.

Studs Terkel Right, right. I think--I'm interested in that matter of that--you, know, about that feeling toward those who have bad luck. Now, well, you know--'cause she object to these giveaways, I suppose. You know, and the young today--coming back to the young--'cause the key point--we're told about a certain coldness on the part of some, a lack of compassion. But they're Ayn Rand readers, and they follow "Atlas Shrugged" and "The Fountainhead". Because I remember in talking at school--I come across--at schools--a good number of them who loved--I said, "What is it you like about Ayn Rand?" "By God, it's about me!" You know, and that she was hitting pretty much, wasn't it?

Barbara Branden Well, but the individual that--for Ayn, the individual was sacred. The most important thing in the world was the single, lone individual. Not a collective, not a group. Groups were composed of individuals.

Studs Terkel Mmm.

Barbara Branden And anything that threatened the individual was, to her, evil.

Studs Terkel Now this--we hear a lot of talk about community--you know, the individual is part of a community.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel How'd she feel toward that aspect

Barbara Branden She would feel that's fine if it's chosen. That is, if you wish to get together with other people for a common purpose, fine. If you don't, fine. That--that--Ayn would not be opposed to anything that--that was voluntarily chosen. I mean, she might think the people were mistaken but that they had a right to do so.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden Uh, but the unchosen, the forced, was what she objected to.

Studs Terkel And I suppose the Civil Rights Act would be what to her?

Barbara Branden She would not--she certainly disapproved of government-legislated morality. She approved of--disapproved of it in liberals just as she disapproved of it in conservatives. But she also was violently antagonistic to racism. She wrote a brilliant article on it. I mean, she considered racism about the lowest form of intellectual position that one could find.

Studs Terkel But for a government to step in and--

Barbara Branden And legislate morality.

Studs Terkel --with legislation, say, "this can't, you know, discriminate in this thing" -- that's forcing people against their will.

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel In fact, she had--didn't she have a South African--what was that called again--Freedom--Free Market Foundation.

Barbara Branden Many of them were Objectivists. Yes, there is a Free Market Foundation in South Africa. Ayn was not connected with it, although many of them were interested in her ideas.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel That's it. "Leave us alone here," you know, they say--

Barbara Branden Well--

Studs Terkel --the Free Market

Barbara Branden No, they were saying to their government, "Leave us alone." Yes, and leave the Blacks alone and the coloreds alone, leave everybody alone.

Studs Terkel Let it take care of itself.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel [unintelligible] would sort itself out.

Barbara Branden Well, it is the case that in South Africa, although things--there are many things wrong there. Nevertheless, Blacks from all the countries in the area are flocking there because conditions are better than in their own homes.

Studs Terkel So, Botha--sorry.

Barbara Branden So, to the extent to which there's a free market in South Africa, it is a better life for Blacks, although still with terrible flaws, than it is in the neighboring countries.

Studs Terkel This is more or less Ayn Rand's--this was her, pretty much, her philosophy.

Barbara Branden Well, this--we're mostly talking about--about political philosophy.

Studs Terkel Yah.

Barbara Branden She had a whole--a whole philosophical system, from metaphysics on. It's a complete philosophical

Studs Terkel Let me ask you about that, what Objectivism is. We'll take a pause for a message.

Barbara Branden Sure.

Studs Terkel We're talking to Barbara Branden, who was as close to Ayn Rand as anyone. And it's her biography. I know she--she talked to you a great deal.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel And, of course, is involved also with your ex-husband to some extent

Studs Terkel We can talk about that if you want to. It's called "The Passion of Ayn Rand"--and passion is a key word here. Barbara Branden, my guest. Doubleday, the publisher. We'll resume after this message. [pause in recording] So we pick up with the discussion of Ayn Rand, who, there's no doubt-- Let's talk a little about that- We'll go back and forth with the book--

Barbara Branden Sure.

Studs Terkel --and the heroes and heroines of both those gigantic novels. Uh, the Reagan administration, you had said, was very much influenced by Ayn

Barbara Branden It's hard for me to know. I know that there are people in it who are influenced. I can't say I see a whole lot of effects on Reagan, but--

Studs Terkel No, I meant the administration.

Barbara Branden Yeah. There are people around him, certainly, who have been influenced.

Studs Terkel Because you point out a number of speechwriters and a number of columnists too, different journalists too.

Studs Terkel We have to talk about the beginnings and your-- What is Objectivism? Now, Objectivism is the philosophy of--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel What is Objectivism?

Barbara Branden Well I'll--I'll explain it as--this is very simplified, but I'll--stated as Ayn often did--it's a paraphrase, but it's pretty close--she said that Objectivism holds that man is a heroic being. Not that every man is always heroic, but that he has the capacity for heroism. That, uh, his happiness is the moral purpose of his life. By which she meant that not only that it's okay to achieve your happiness or pursue your happiness--it's a moral good to do so. That's why you're alive. That's what makes life worthwhile. It holds that productive achievement is man's noblest activity. [match being lit] And it holds first and foremost and most basically that reason is man's only absolute. As opposed to any form of faith, religious or otherwise. So, as you can see, this made her unpopular with many liberals and many conservatives.

Studs Terkel Some would say that's being self-centered and selfish. It was an accusation.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel It's an ode to selfishness and self-centeredness.

Barbara Branden It's an ode to rational self-interest, yes. Which she often called selfishness, sort of on the premise "if this be treason, make the most of it."

Studs Terkel Yeah. And so the young, many of those we call yuppies--you know, upwardly mobile people--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --the young--and some people say, "What's happened to them?" The answer could be, to some extent, Ayn Rand!

Barbara Branden It depends. If they're trying to--to the extent to which they're trying to better their lives--

Studs Terkel Mhmm.

Barbara Branden Uh--and grow and learn and achieve and produce, yes, it could be Ayn Rand.

Studs Terkel You know, as you say, I remember--when she testified against some of those writers in those movies in which they would kind of slip in some of that, as she would say, you know, Red propaganda or something. I mean-- There was one film called "Kitty Foyle". Dalton Trumbo, one the Hollywood Ten wrote it.

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel And Sheila [sic] Rogers, the mother of Ginger Rogers--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --testified before the Committee--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --that this was a communist, hidden thing. Because one of the lines was, "Share and share alike, that's democracy." And that was one of the lines in the film.

Barbara Branden That's very interesting. I didn't know that.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden I would have to know the context.

Studs Terkel No, I mean--but I imagine Ayn Rand--

Barbara Branden No, she wouldn't like that. Well--

Studs Terkel "Share

Barbara Branden I mean, she shared with her husband. But first of all, it's not democracy. Democracy has a specific meaning, which "share and share alike" has nothing to do with. I mean, I don't even know what that means, quite--"share and share alike." If it means sharing what you want to share with people you care about, fine. If it means you owe everything you've got to other people, not fine.

Studs Terkel Yeah. Well I like those--that aspect--earlier--to come back to the young of today. Changes, see. Because, remember, changes- we have changed considerably since the old days of FDR and the New Deal.

Studs Terkel

Barbara Branden

Studs Terkel [reading] "Ayn Rand was led to define two different ways of facing life. Two antagonists. Two types of men: The man of self-sufficient ego, of first-hand, independent judgment, the man whose convictions, values, and purposes are the product of his own mind -- and the parasite who is molded and directed by other men. The man who lives for his own sake, and the collectivist of the spirit who places others above self. The prime mover whose source of movement is within his own spirit, and the soulless being who is movement without an internal mover. The creator and the second-hander. The culture has changed since the '40s, in significant part, as a result of the works of Ayn Rand. Her ideas have spread, they have been heard, they have made a difference. The book and reality are working." Those are two, I think, very telling sequences in the book, the biography of Ayn Rand, author of "The Fountainhead" and "Atlas Shrugged", among other works, by someone who's very close to her down through the years, Barbara Branden, published by Doubleday. And I'm thinking of Ayn Rand, and especially those two books, and her effect upon the young, and the change in the way we think today, a great many of us do. The first part you read, Mrs. Branden, that part about two kinds of people in the world-- Yes. One kind that's self-sufficient, out for self, by God, above Yes indeed. Without sacrificing the rights of other people-- Mhmm. --but out for self, yes. Out for self. As against-- What Ayn called "the collectivist of the spirit" whose values are formed because they're the values of others, whose goals are chosen because they're the goals of other people, who doesn't set his own purposes. Even though, I think--once called the outer-directed person against the inner-directed person, something like-- Ayn would not use those terms, because-- That was Riesman, a guy named Riesman. Yes, that's right. But you wouldn't use those terms. No. No, they wouldn't quite fit. But you're saying--the, uh--the one, the collectivist of the soul who places others above self-- Yes, She was against that. She was passionately against Yeah, no place-- She thought it was--it was very dangerous and very bad in a man's soul. It made him a robot, pushed and pulled by others. And, in politics, it made him accept dictatorship, the rule of others, whatever. It made him--it made him an acceptor, not an initiator. Placing others above--so someone like, I suppose, Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King would not rate too high in her book. Would No, no. They would not. Mahatma Gandhi? Yeah. No. No, that would be, to her, the model of the altruist, whose life was sacrificed to others--and who was not above telling others what to do, which is usually the case. That's interesting. There's nothing adorned in this thing. It's direct, straight. This is it. She said it straight. And the chips fell where they fell. And there was a lot of antagonism to many of her ideas because she never pussyfooted about them. And so, see--what fascinates me about this--[unintelligible] now years later, today, many of the young are followers of Ayn Rand's philosophy of self above all -- you, the person -- who call it "the me decade" or whatever they want to call it. It's not quite "the me decade," and Ayn would not have liked a lot of what that stands for. Because she was very clear on something: She did not believe you live by whim or emotion. You don't just, if you feel like doing something, then you go do it and that's all that matters. Ayn was first and foremost a rationalist. She believed that whatever goals you chose, you had to rationally justify. That you didn't just decide "well, being cruel to people makes me happy, so my happiness is important, I'll do it." You had to have a rational justification, for your actions and for your purposes. I'm thinking that--rational justification of so many of the young today are out making it, and making it big. Yes. You know, and, in a way, devil take the hindmost--make it big, you know. Yes. Ayn Rand disciple. I mean, she's had an effect on them. She's had a profound effect on our whole culture. I did a fair amount of research on that [match being lit] and discovered finally that there was--there was a book to be written there. It was a fa- It's a fascinating story. She began writing--her first novel was published in the '30s. It was an anti-communist book published in the Red Decade. She did not make a The Red Decade, you say. Of the '30s. It's been called the Red Decade. Oh, the Red Decade. Why? Because of the New Deal and-- Because of the love affair with Soviet Russia, the noble experiment. Uh--and so--she was in trouble then. "The Fountainhead", which is a hymn to the individual, was published in the '40s. Then "Atlas Shrugged", which is a hymn to the--to the genius, to the men of accomplishment, to the men of the mind, as she called them, was in the late '50s. Throughout all this, her influence has been growing and growing and growing. It's--originally it was very underground. One didn't see it publicly, and one didn't normally see it in public people. Today that's no longer so. Everywhere I looked I found prominent people, not necessarily accepting all of her ideas, but deeply influenced by many of them. And in colleges, if they were professors, teaching some aspect of her ideas. Putting them into practice in their lives, in whatever field they worked in. Yeah, in fact, in this very administration-- Yes, yes indeed. Alan Greenspan has been very influenced by One of the economic advisers to-- to Rea-- --President Reagan. Yes, He's an Ayn Rand disciple. No, he's not--he--I wouldn't call him an Ayn Rand disciple. He was influenced by her. He was. And agrees with many of her ideas, and certainly in the field of economics. And some of the Reagan speechwriters. That's right. Yes. Someone of- There isn't a field where you will not find prominent people influenced by her. Certainly including philosophy. Yeah. And among the philosophers too. Hayek and others. Yes, yes. Who admire her work. Yes indeed. And, and- By the way, we always talk of universities as, you know, for years, we think of universities as centers of radical thought. Yes. That is, of left thought, subversion. You're pointing out that many of the teachers at universities are Ayn Rand Yes, that--well, in that sense, the universities are still the centers of radical thought. They are? Because Ayn was considered very radical, although not to the left. [unintelligible] Yes. She was the one voice of protest against the left. Mmm. When I went to UCLA, when I first met her, and I was the campus pariah. Because I was arguing--I think with more heat than light--pro-free enterprise, and found that people were not talking to me. I mean, this was considered next door to an obscenity in those days. Today it's quite acceptable. When you say free enterprise, the entrepreneurial spirit you're talking about. Yes, That's one of the things--when Ayn Rand testified as a friendly witness for the House Un-American Activities Committee against subversion in movie scripts, against-- Yes. --communism hidden in the scripts. Did she have evidence of that? Cases of that? Oh yes, she did indeed. And Like what? She was extremely upset that she was not allowed to testify as she had been told she could testify. She was not interested in citing chapter and verse about what line of propaganda was in what movie. What she wanted to do was talk about how one recognizes propaganda in movies, what form it tends to take. For instance: If, for a period of time one doesn't see a movie in which there's a businessman who is anything but a villain, notice that. Watch. Maybe you're being--something is being communicated to you. Uh, issues like that. They had promised that they would give her a--the Committee had promised they would give her time to testify about it, and they didn't. She was very upset and felt the whole thing, for her, was a complete waste of time. She was watching certain movies where the businessman was considered someone less That was one of the issues. --ethical. Yeah. Where profit-making was presented as sinful, giving away everything was good. What were some examples that she cited? There was a movie, oh dear--"The Best Years of Their Lives" was one of "Best Years of Our Lives"? Yes, That was a subversive film, then, No, no, no. She didn't--she didn't consider it subversive, no. But that was a film that did what? I mean--she didn't--by the way, she did not think anyone should go to jail or be prohibited from making any movies they wanted. She thought only that the American public, if they're going to accept certain ideas, should know that they're accepting them. Ah. Should recognize them. That--they're free, obviously, to accept whatever they want. But let them know what it is. Let it not happen by osmosis. "Best Years of Our Lives", I remember, it was a very popular-- Yes, it was. --with Fredric March and Myrna Loy, as I recall-- Yes, --and Harold Russell, the--you know, the armless vet. Uh, what was it in that film that she detected-- As I remember, that the banker decides, ultimately, that morality requires that he give loans to the poor without collateral. And that was virtue. I mean, that also breaks banks and destroys all the other depositors--but that was ignored. Virtue is to give away. And in this case, it would be other people's money as well, because they would be destroyed. That's interesting, because Ayn Rand's--she's straight. There's no doubt about her. [laughter] She doesn't hide what her philos- or her feelings are. No, "By God, you've got it. Don't you dare worry about that person who's--has tough luck." No, no, she wouldn't say that, quite. Um- [laughter] I remember at a talk she gave at Yale once--there's a sense in which she would say that--but in a talk she gave at Yale, a very angry questioner said to her, "Okay, in your society who's going to look after the janitors?" And she said, "The janitors." So, yes, there was an extent to which she thought, certainly people should look after themselves. Yeah. However, she was certainly not opposed to generosity. If there's someone one wants to help, someone one values and one wants to help, that was perfectly fine. Ah, what she objected to was involuntary help. Ah. So the idea of charity, fine. Yes, yes. But not governmental role--like the New Deal, I suppose. The New Deal of the 30s was probably anathema to her. Yes, it was indeed. It was indeed. What was it about the New Deal that Well, it was as close to statism as this country ever got. I mean, it was an attempt to have state control of the economy. The NRA--the state was to control business and industry. We were on our way in a direction, she considered, she had just escaped. She had come from communist Russia, and she did not want to see the first steps of that again. New Deal as a step toward-- Yes. I mean, it's not that she thought they were all communists. She didn't. That wasn't the No, no. But a Ayn was not seeing communists under every bed. That wasn't her style. Not every bed. Not even most. No, she was much more concerned with the philosophical underpinnings. Right, right. I think--I'm interested in that matter of that--you, know, about that feeling toward those who have bad luck. Now, well, you know--'cause she object to these giveaways, I suppose. You know, and the young today--coming back to the young--'cause the key point--we're told about a certain coldness on the part of some, a lack of compassion. But they're Ayn Rand readers, and they follow "Atlas Shrugged" and "The Fountainhead". Because I remember in talking at school--I come across--at schools--a good number of them who loved--I said, "What is it you like about Ayn Rand?" "By God, it's about me!" You know, and that she was hitting pretty much, wasn't it? Well, but the individual that--for Ayn, the individual was sacred. The most important thing in the world was the single, lone individual. Not a collective, not a group. Groups were composed of individuals. Mmm. And anything that threatened the individual was, to her, evil. Now this--we hear a lot of talk about community--you know, the individual is part of a community. Yes. How'd she feel toward that aspect of-- She would feel that's fine if it's chosen. That is, if you wish to get together with other people for a common purpose, fine. If you don't, fine. That--that--Ayn would not be opposed to anything that--that was voluntarily chosen. I mean, she might think the people were mistaken but that they had a right to do so. Yeah. Uh, but the unchosen, the forced, was what she objected to. And I suppose the Civil Rights Act would be what to her? She would not--she certainly disapproved of government-legislated morality. She approved of--disapproved of it in liberals just as she disapproved of it in conservatives. But she also was violently antagonistic to racism. She wrote a brilliant article on it. I mean, she considered racism about the lowest form of intellectual position that one could find. But for a government to step in and-- And legislate morality. --with legislation, say, "this can't, you know, discriminate in this thing" -- that's forcing people against their will. Yes, In fact, she had--didn't she have a South African--what was that called again--Freedom--Free Market Foundation. Many of them were Objectivists. Yes, there is a Free Market Foundation in South Africa. Ayn was not connected with it, although many of them were interested in her ideas. Oh they are. Yes. That's it. "Leave us alone here," you know, they say-- Well-- --the Free Market Foundation. No, they were saying to their government, "Leave us alone." Yes, and leave the Blacks alone and the coloreds alone, leave everybody alone. Let it take care of itself. Yes. [unintelligible] would sort itself out. Well, it is the case that in South Africa, although things--there are many things wrong there. Nevertheless, Blacks from all the countries in the area are flocking there because conditions are better than in their own homes. So, Botha--sorry. So, to the extent to which there's a free market in South Africa, it is a better life for Blacks, although still with terrible flaws, than it is in the neighboring countries. This is more or less Ayn Rand's--this was her, pretty much, her philosophy. Well, this--we're mostly talking about--about political philosophy. Yah. She had a whole--a whole philosophical system, from metaphysics on. It's a complete philosophical system. Let me ask you about that, what Objectivism is. We'll take a pause for a message. Sure. We're talking to Barbara Branden, who was as close to Ayn Rand as anyone. And it's her biography. I know she--she talked to you a great deal. Yes. And, of course, is involved also with your ex-husband to some extent too-- Yes. We can talk about that if you want to. It's called "The Passion of Ayn Rand"--and passion is a key word here. Barbara Branden, my guest. Doubleday, the publisher. We'll resume after this message. [pause in recording] So we pick up with the discussion of Ayn Rand, who, there's no doubt-- Let's talk a little about that- We'll go back and forth with the book-- Sure. --and the heroes and heroines of both those gigantic novels. Uh, the Reagan administration, you had said, was very much influenced by Ayn Rand. It's hard for me to know. I know that there are people in it who are influenced. I can't say I see a whole lot of effects on Reagan, but-- No, I meant the administration. Yeah. There are people around him, certainly, who have been influenced. Because you point out a number of speechwriters and a number of columnists too, different journalists too. Yes, yes. We have to talk about the beginnings and your-- What is Objectivism? Now, Objectivism is the philosophy of-- Yes. What is Objectivism? Well I'll--I'll explain it as--this is very simplified, but I'll--stated as Ayn often did--it's a paraphrase, but it's pretty close--she said that Objectivism holds that man is a heroic being. Not that every man is always heroic, but that he has the capacity for heroism. That, uh, his happiness is the moral purpose of his life. By which she meant that not only that it's okay to achieve your happiness or pursue your happiness--it's a moral good to do so. That's why you're alive. That's what makes life worthwhile. It holds that productive achievement is man's noblest activity. [match being lit] And it holds first and foremost and most basically that reason is man's only absolute. As opposed to any form of faith, religious or otherwise. So, as you can see, this made her unpopular with many liberals and many conservatives. Some would say that's being self-centered and selfish. It was an accusation. Yes. It's an ode to selfishness and self-centeredness. It's an ode to rational self-interest, yes. Which she often called selfishness, sort of on the premise "if this be treason, make the most of it." Yeah. And so the young, many of those we call yuppies--you know, upwardly mobile people-- Yes. --the young--and some people say, "What's happened to them?" The answer could be, to some extent, Ayn Rand! It depends. If they're trying to--to the extent to which they're trying to better their lives-- Mhmm. Uh--and grow and learn and achieve and produce, yes, it could be Ayn Rand. You know, as you say, I remember--when she testified against some of those writers in those movies in which they would kind of slip in some of that, as she would say, you know, Red propaganda or something. I mean-- There was one film called "Kitty Foyle". Dalton Trumbo, one the Hollywood Ten wrote it. Yes, And Sheila [sic] Rogers, the mother of Ginger Rogers-- Yes. --testified before the Committee-- Yes. --that this was a communist, hidden thing. Because one of the lines was, "Share and share alike, that's democracy." And that was one of the lines in the film. That's very interesting. I didn't know that. Yeah. I would have to know the context. No, I mean--but I imagine Ayn Rand-- No, she wouldn't like that. Well-- "Share I mean, she shared with her husband. But first of all, it's not democracy. Democracy has a specific meaning, which "share and share alike" has nothing to do with. I mean, I don't even know what that means, quite--"share and share alike." If it means sharing what you want to share with people you care about, fine. If it means you owe everything you've got to other people, not fine. Yeah. Well I like those--that aspect--earlier--to come back to the young of today. Changes, see. Because, remember, changes- we have changed considerably since the old days of FDR and the New Deal. Oh, yes indeed. Certainly. Yes. And

Barbara Branden Yes, she did indeed. Like so many other people, uh, she once told me she had voted for Roosevelt--

Barbara Branden --the first time, on the grounds of his stand against prohibition. She was new in this country--uh, she didn't really understand much about American politics but she was convinced that--she didn't drink, but she was very much against prohibition because it was the government legislating morality.

Studs Terkel The Libertarian Party today--the Libertarian Party [unintelligible]-- is founded to a great extent on Ayn Rand's philosophies.

Barbara Branden Yes. When it was--on her political philosophy. When it was first formed they adopted, as part of their platform, a statement from her work which is that no man has the right to initiate force against any other man. Uh, the Libertarian Party has changed a lot over the years, that they now hold certain ideas that she would disagree with. But that was the base. And it was her base, from which they started.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden And of course, now there's an enormous libertarian movement around the world. Which, again, ultimately stems from Ayn Rand.

Studs Terkel And it primarily--let the government stay away from us as far as possible.

Barbara Branden Leave us alone. Leave us alone to make our own lives.

Studs Terkel The one thing about the Libertarian Party she might not have liked, is their attitude toward foreign policy. Libertarians are against military buildup.

Barbara Branden Some of them are, some of them are not. There's so many factions now in the Libertarian Party. Uh--there's people, unfortunately, for unilateral disarmament, there's people who want this country to bristle with arms--and all variations in between. Uh, no--her view would have been--ideally what Ayn would have wanted is a kind of "Fortress America." But--

Studs Terkel A "Fortress America." How--

Barbara Branden Yes. That is that--that we'd be armed, that we protect ourselves, and we deal only with those people that we can profitably deal with. And not attempt to save the whole world. Or to--or to tell them how to live or what political systems to live under. That we focus on ourselves.

Studs Terkel But, again, the strong impact--because I repeat this--I remember anywhere I lectured at a college, there were two or three or four, at least, who said, "Have you read 'The Fountainhead'? Or 'Atlas Shrugged'?" So we have to come to the heroes and heroines of those two books, don't we?

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel So let's [laughter] talk about "The Fountainhead." And--it deals with an archit--she chose an architect.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Howard Roark as the hero.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel An architect.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Did she have Frank Lloyd Wright in mind?

Barbara Branden No, she didn't. She--not the person. She didn't meet him 'til after she'd finished "The Fountainhead". But she, in a way, had his work in mind. She liked his work very much. But she had decided that she was going to write about an architect when she was still in Russia. When she was a young girl [match being lit] she had--American movies had finally come to the Soviet Union, and she had seen distant glimpses of the skyline of New York. And that came to symbolize America to her, and to symbolize human achievement. And she had decided then that she wanted, one day, to write a book about--about a skyscraper, and about a man who builds skyscrapers.

Studs Terkel And this is Roark.

Studs Terkel A strong man. And the heroine whom he meets, this aristocratic, cool Dominique.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel And this--there's something between them.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Electricity. That one part where he overcomes her--

Barbara Branden Yes, yes. It's--

Studs Terkel I wonder how feminists would feel about that. He overcomes her and she fights, but not too hard.

Barbara Branden Right.

Studs Terkel She delights in being overcome.

Barbara Branden Yes. It's often called by people "the rape scene" in "The Fountainhead". But Ayn once said, when asked about it, that if it was rape, it was rape by engraved invitation. [laughter] And it was. I don't know, I suppose a lot of feminists wouldn't like it. But Ayn had very odd views on feminism. She shared a view which, to my mind, unfortunately, is held by a number of women of great achievement, which is that, "Well, I did it. I did it myself. Nobody else helped me. Any woman can do it if she has the ambition and the brains." I think that's very oversimplified and that there are real problems. Ayn certainly thought men and women should be equals--certainly under the law and in every other way. But she was always intrigued by--and very much liked the idea of men as superior to women. Not in any legal sense, not in the sense of rights. But a force of drive, of intellect--that was very attractive to her.

Studs Terkel Superior in intellect to the woman.

Barbara Branden Yes, yes. That she liked. And I think--I think part of why she liked it--she had truly a great mind. And I think such a mind is starved for minds to admire. And that that was very psychologically relevant to her desire to be a hero-worshipper, to find a man that she could look up to.

Studs Terkel Yeah. Well obviously she caused quite a stir, didn't she?

Barbara Branden She did indeed. [laughter] Her whole life.

Studs Terkel Now the villain--some of the prototypes for the villain in the book--there's a Toohey, who's a critic.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel And [unintelligible] book--she modeled after someone like Lewis Mumford.

Barbara Branden Yes. That was a slight influence. The--

Studs Terkel The villain was Lewis Mumford. Someone like Lewis Mumford.

Barbara Branden Like that. But mostly, it was modeled after Harold Laski.

Studs Terkel Harold Laski, the head of the London School of Economics.

Barbara Branden Yes, the British Fabian socialist. Yes. She had gone to a lecture at which he spoke, and she had been working on--

Studs Terkel [coughs,

Barbara Branden --working on the plot, outlining "The Fountainhead".

Studs Terkel Mhmm.

Barbara Branden And she told me that when she saw Howard Laski, she knew she had Ellsworth Toohey. That the physical appearance and the manner were exactly what she wanted for the type of human being she had in mind for Toohey. And so she went back and heard another lecture and drew pictures.

Studs Terkel So his--his philosophy, too--

Barbara Branden His philosophy, too, was very relevant.

Studs Terkel He was--she call, certainly--a collectivist, I suppose.

Barbara Branden A collectivist of the spirit, yes.

Studs Terkel Of the spirit. Collectivist of the soul, of the spirit.

Studs Terkel Who were her heroes in life?

Barbara Branden Oh, George Washington [laughter], Thomas Jefferson, uh, Victor Hugo--

Barbara Branden As a matter of fact, she knew very few big tycoons. Uh, she would have liked to know specific ones she admired, but Ayn led a very reclusive life. Her life was spent predominantly at her desk. And, uh, although in many ways it was an exciting life--because of a lot of the problems, in the inner conflicts, and the battle to be recognized--she did not have a wide social life. And simply didn't meet people like industrialists, except on very rare occasions.

Studs Terkel They were the heroes of her books, a great many of

Barbara Branden The heroes certainly of "Atlas Shrugged", yes.

Studs Terkel This is her way of answering those Hollywood writers who painted some of these guys--

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel --in less than glowing terms, she felt.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel But Victor Hugo--that's intere--you pointed out that as a young writer--young woman--she liked Victor Hugo.

Barbara Branden That was a real passion. She loved his work. That was--he was really her favorite of any writer she'd ever read.

Studs Terkel Let's take a break here.

Barbara Branden Sure.

Studs Terkel One more break and then we'll pick up with Barbara Branden and her biography of Ayn Rand, called "The Passion of Ayn Rand". And it's, uh, Doubleday the publisher. We'll resume in a moment. [pause in recording] Resuming with Barbara Branden. How would you explain, as her close friend for many years and her biographer--of course she talked to you a great deal about--she knew you were doing this book

Barbara Branden She knew--I had told her, when I decided on it, which was only a few months before she died. I did not know she was ill. But I had not been seeing her, and [match being lit] I wrote her a letter and told her. I wanted her to learn it for me not from someone else.

Studs Terkel But how would you explain what has happened--if you feel like, okay--during these past years to emphasize the change when--she was read underground but her philosophy was not so dominant as it is today, in this world. And especially among the

Barbara Branden I think it takes time. Well, you know, she had an influence among the young from the very beginning, except they were young. Uh, what's happened--at the time that "Atlas Shrugged" was published, my then-husband and I created an

Studs Terkel Nathaniel Branden.

Barbara Branden Yes. A lecture organization. We and some associates lectured in 80 cities around the country on her philosophy. And it was--there were a great many young people who were involved. But it takes time before that--the young are in positions to make things happen. They are today. And a lot of those young students are now doing very interesting things, and there's been other generations of young students since, who are coming out into the world and making their own way. So one's seeing today the end result of all those years of people reading her books and being influenced by them. They're now taking form in action.

Studs Terkel So those young, whom we say, who were out to make it, you know, who want to rise to the top. To make it. Aggressively. Ayn Rand, in a way, represents that philosophy.

Barbara Branden In

Studs Terkel Now, somebody may be hurt along the way, but that can't be helped.

Barbara Branden Well, it depends what you mean by "hurt." If you're in business and you do better than your competitor and he's not able to continue, Ayn would not consider that you hurt him. Yes, he has to close his business. But, in fact, the consumer is better off if you're doing a better job. Your competitor is better off if he's no longer in a business which is not productive. He has a chance to do something which is productive instead.

Studs Terkel And so--sorry.

Barbara Branden If the hurt consists of infringing on his legal rights, then she would say you have no right to do it.

Studs Terkel I imagine she would not be too unhappy today with the way things are going, today.

Barbara Branden She was. She--she told me-- I last saw her in 1981, and I happened to ask her what she thought of Ronald Reagan and she said something very interesting. She said she had not voted for him.

Barbara Branden No, she didn't. And she didn't like him. [clears throat] And she said the reason is his stand on abortion. She said that it was her conviction that a man who did not believe in a woman's right to dispose of her own body if she chose, basically did not believe in any human rights. And she didn't trust him.

Studs Terkel That's interesting. Her stand, uh--she was pro-choice on abortion.

Barbara Branden Yes, definitely, definitely.

Studs Terkel But then--on every--so on that one aspect--but today she wouldn't mind his economic or foreign policy.

Barbara Branden She would like certain aspects of it, but many not, no. She would have had very, very mixed feelings about. Since his administration is very mixed in its political philosophy.

Studs Terkel Now we come to the big novel, "Atlas Shrugged".

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel That was the big one, isn't it?

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Not that "Fountainhead" is small. They sold in the millions, didn't

Barbara Branden Her books have sold over twenty million copies in

Studs Terkel total. Twenty million. What, "Atlas Shrugged" did?

Barbara Branden "Atlas Shrugged"--well, all

Studs Terkel Oh, both. Twenty million

Barbara Branden Yes. And today--it's fascinating. In paperback, her books today sell the equivalent of new bestsellers every year.

Studs Terkel And now here we have a railroad magnate as the hero.

Barbara Branden Mhmm,

Studs Terkel And here there's the heiress Dagny Taggart.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel A similar relationship of overcoming, isn't there?

Barbara Branden Yes. But Dagny is a very different woman than the heroine of "The Fountainhead". Dagny is a much more--Dominique in "The Fountainhead" is a much more troubled woman with inner conflicts. Dagny is not. She's a very confident, aggressive woman, aggressive in business, a very passionate woman, very certain of herself. In those respects, very like the male heroes.

Studs Terkel And there's also the young- there's a young guy who has some [unintelligible]--it says despite college--there's a young boy called Wet Nurse.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Who loves this big shot, the big guy.

Barbara Branden Yes. Hank Rearden.

Studs Terkel And he breaks right through whatever it may be, picket lines or things--

Barbara Branden He was supposed to hate him. He'd been taught in college that the industrialist is the symbol of evil. And he finds that he admires Rearden and loves him. And ultimately acts on that. Against all his supposed principles.

Studs Terkel So, many of the young today have become Wet Nurses, a lot like this character,

Barbara Branden Yes, that's true. That's true. Yes.

Studs Terkel So, I was thinking of our own tempestuous--oh, the trader, also--the man who trades--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --goes back and forth. He's one of her heroes too.

Studs Terkel That's the freebooter.

Barbara Branden Yes. You know, in many ways, Ayn, I think, gave America its voice most specifically.

Studs Terkel The

Barbara Branden Gave America its voice. Because a great many of the things she taught, of the things she admired, were very American characteristics: Individualism [match being lit], the trader, uh, industrial--the value of industrialism. These have always been very typical of America, but they've never been given a philosophical justification. Ayn was the first person to do that.

Studs Terkel How did she feel about trade unions? Unions.

Barbara Branden She thought unions were okay, if predominantly a waste of time, if they were voluntary. She did not think that the reason workers in a free society get more money is because they unionize. But it's a result of production. So that she had no objection, as I say, to any voluntary coming together. But she simply didn't think it was very effective.

Studs Terkel Yeah, I see toward the end of the book--the head of J.P. Stevens, you know, that big outfit--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --is an Ayn Rand follower.

Barbara Branden Yes. He was a student at our institute years ago.

Studs Terkel [laughter] It's interesting. They had, you know, a pretty long, drawn-out strike there, you know.

Studs Terkel Yeah. There's no doubt--I mean, you can't say that she waffles on issues.

Barbara Branden [laughter] Nobody has ever said that

Studs Terkel No, she just--that's it, that's it. And, see, what interests me, again [match being lit], is this whole subject of the young and Ayn Rand. But--Howard Roark builds a housing project.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel It wasn't right--quite right--so he destroyed it.

Barbara Branden Well, that's essentially true, but- may I just add something? He had the job of building this housing project because he was the only architect who could solve certain very complex, technical problems that no one else had been able to solve. And he agreed to do it on one condition: That it be built exactly as he designed it. If they weren't willing to do that, fine, they would go to someone else. They were willing to do it. And that was his contract. The contract was breached. It was a contract with the government. You can only sue the government with its consent. He wasn't about to get the consent of the government. He blew up the building because it was the only means of protest he had. There was nothing legal he could do about it. And he was quite willing to go to jail if necessary. It was really a case of civil disobedience.

Studs Terkel You know what I was thinking of--civil disobedience? I like that.

Studs Terkel --civil disobedience for an Ayn Rand hero. Martin Luther King comes to my mind. Did she have any thoughts about him?

Barbara Branden She never talked much about him. Uh, to the extent that he wanted the government to legislate such things, she would have been

Studs Terkel Yeah. How'd she feel, you know, when a couple of big banks almost had runs recently and were saved by government subsidy and loan, or Penn Central--

Barbara Branden She was very much opposed to that. Extremely opposed to that.

Studs Terkel Now, if they went broke, or that bank had a run on it, you know, another bank had a run on it--that was one of the beginnings, one of the beginnings, of the depression of the '30s and [unintelligible]--

Barbara Branden Yes. I think there are a great many economists writing today and writing for years who have given- written lengthy treatises on the crucial role of government policy in getting us into the Depression. Uh, that it was not the free market that created the Depression. It was government interference with the free market. And this was certainly Ayn's position.

Studs Terkel Government interference--

Barbara Branden In

Studs Terkel --created the depression of the '30s.

Barbara Branden Yes, yes. By--by its, uh, position on money, by what it was doing with the money supply. Uh, by its manipulation of the stock market. There were all

Studs Terkel The government manipulated the stock market?

Barbara Branden The government--the Federal Reserve Board, government institutions. I don't know all the details of it. I know this was her position

Barbara Branden I know there's been a lot written about it.

Studs Terkel That's the part I find interesting. Her interpretations of history and of things--how they happened. But it's also another thing: The good and evil. I mean, she's pretty certain as to what is good and what is evil.

Barbara Branden Yes, she was. She was. That's true. In my mind, sometimes too much so. This was an area in which I had some difficulty with her ideas. That there was a very quick--a tendency to very quick moral judgments and very final moral judgments. On people, on institutions, on a lot of things.

Studs Terkel Which leads to the personal aspects of it, because your ex-husband was one of the spokesmen for the Objectivist movement.

Studs Terkel And here came personal difficulties.

Studs Terkel And there's talk about the fire of Ayn Rand when--

Barbara Branden [laughter] Yes.

Studs Terkel --she was considerably older than he was.

Barbara Branden Twenty-five years

Studs Terkel And there was a romance.

Barbara Branden Yes there was.

Studs Terkel And then he left her. But then her explosion is something you've got to read, because it's very eloquent, it's very fiery.

Barbara Branden Yes

Studs Terkel Uh--

Barbara Branden It was not--the fire was not simply because he left her and fell in love with another woman. It was because he didn't tell her that for almost four years.

Studs Terkel He was afraid of her.

Barbara Branden Yes he was. Yes

Studs Terkel [laughter] Somewhere along the line--about "how dare you"--you should read some of that.

Barbara Branden This is the scene in which Ayn has learned that Nathaniel has lied to her for 4 years, has said he was in love with her but in fact was in love with another woman, which--and Ayn did not know it. And I say [reading] "Her voice went on and on, filling the room with its implacable agony. There is a point at which pain wrenches the human spirit into twisted, unrecognizable shapes. Ayn had reached that point. As the years of unmet needs seemed, for the endless tragic space of that evening, to have shattered what she had been, shattered what she was. Her eyes were huge and blazing. She said, 'How did you dare aspire to me? If you ever, for even a moment, had been the man you pretended to be, you would value me romantically above any woman on earth. If I were 80 and in a wheelchair, you'd be blind to all other women. But you've never been what I thought you were. It was an act from the beginning, a sick ugly act.'"

Studs Terkel Well,

Barbara Branden [reading] "It was a very painful evening to be present at."

Barbara Branden [reading] "And hideously painful for her. For all of us."

Studs Terkel "How dare you aspire to me?" Yeah. "You dare to reject me!" Now, I suppose--her opinion of herself, I mean, it was--

Barbara Branden It was high. Yes,

Studs Terkel it It was high. And, uh--

Barbara Branden And she had every reason to believe that Nathaniel shared that opinion.

Studs Terkel That everyone did.

Barbara Branden No, not that everyone did, but that certainly Nathaniel did.

Studs Terkel Yeah. But in any event, let's take one pause because we have to come to the last lap, now, of this--to put it mildly--fascinating study of Ayn Rand.

Studs Terkel The biography. In the early days, too--I didn't know that she wrote the big hit, "Night of January 16th".

Studs Terkel That was a play. A courtroom play. A mystery play.

Studs Terkel And she wrote that in the early days. Doubleday, the publishers. And for the last lap with the biographer of Ayn Rand, Barbara Branden. [pause in recording] And so this is the last lap. So, where does this leave us today? The biography goes back to beginnings when she's--and she expresses, as a little girl, contempt for others who might have a different opinion,

Barbara Branden Yes, that amazed me--

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden --in my research and in--contempt is so adult a concept, it seems to me. And yet I found that the little girl felt something that can only be called contempt for people who were less bright than she, less honest than she, didn't understand what seemed very clear to her. That was--that was quite surprising to me, to discover that.

Studs Terkel A contempt for those who are less honest than she. Of course, she says I--some would say, "You've got to give her credit because she says what she thinks."

Barbara Branden Yes,

Studs Terkel And who are less--

Barbara Branden She did not admire people who fail to say what they think -- or more importantly, who fail to think.

Studs Terkel Fail to think. And she was--she considered herself a thinker, of course.

Barbara Branden Yes indeed. Yes indeed.

Studs Terkel And, uh, women were especially--those of--toward whom she felt contempt.

Barbara Branden Well, not--not the species. Not the entire gender, by any means. I mean, one of her greatest characters was Dagny Taggart. But the women around her in those days--little Russian girls--simply did not interest her. Their concerns were not hers. She was interested in reading and in writing. And she enjoyed school work. And they didn't seem to care about those things. Nor- nor did they seem to care about the values that were very important to her. So she just wasn't interested in them.

Studs Terkel Yeah.

Barbara Branden And was really never part of the world of other little girls. She very much went her own way from the beginning.

Studs Terkel And so when they left the Soviet Union, she and her family, little--then the movies. And of course Cecil B. DeMille became one of her--one of her mentors.

Barbara Branden That's right. Yes, she had--he had been her favorite director when she was in Russia. She'd seen some of his movies and she loved them. And she met him in Hollywood-- "The Ten

Studs Terkel "The Ten Commandments" and--

Barbara Branden Yes. And he made her an extra on the set of "The King of Kings"--

Barbara Branden That was her first job in this country. Yes.

Studs Terkel And then she wrote film. Then--and then she wrote, you know, the screenplay for "The Fountainhead".

Barbara Branden Yes. Yes she did.

Studs Terkel [unintelligible] So, as to what--what would you say as to the legacy of Ayn Rand today, especially among young or those who are--have a say or two in the way we think

Barbara Branden It's an enormous legacy. And I think one can't even today fully know what it is. And the, uh--I talked to so many people about the effect of her ideas, and I get slightly different attitudes from different people who are influenced by her. Some say, "the thing that was most important to me was 'reason,' the absolutism of reason." Others will say it's her moral theory. Others will say it's her political theories. They all seem--all aspects of her philosophy, essentially, seem to be having a significant effect on a significant number of people. How it will all come out in the end, I just don't know.

Studs Terkel Here's Billie Jean King, the tennis champion--

Studs Terkel And she's discussing the effects of "Atlas Shrugged" on her.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel [reading] "The book turned me around, because I was going through a bad period in tennis and thinking about quitting. People calling me and making me feel rotten if I didn't play their tournament or help them out. I--people were beginning to use my strength as a weakness, using me as a pawn to help their own ends." And then, "So, like Dagny Taggart"--who is the heroine of "Atlas Shrugged"--"I had learned how to be selfish, although selfish has the wrong connotation. As being selfish is really doing your own thing." And so- "if that's being selfish, so be it. That's what I am."

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel So that pretty much influenced a great deal of those we today who--

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel --are young or a little older too.

Barbara Branden Yes. Yes indeed. That it's not a sin to do what you want to do, what makes sense to you to do. That it's good to do that.

Studs Terkel But if around you, someone who's up against it--if you want to help that person out, by all means do so.

Barbara Branden Of

Studs Terkel But for the government to say, "Wait a minute, we've got to help them out." That's--

Barbara Branden That's a different issue. That's force.

Barbara Branden Yes. You don't do it, you go to jail.

Studs Terkel But force--forced to do what?

Barbara Branden To do anything.

Studs Terkel Forced in a bad way. You mean, so if--but suppose you don't feel like contributing, or whatever it might be, to that person up against it, who's having a rough time?

Barbara Branden Then you don't have

Studs Terkel Then you don't--and nobody--suppose nobody--then that's it, tough luck.

Barbara Branden Well, yes. Except, you know, Ayn pointed out something that was very interesting, that the freer the society, the more men [clears throat] do not have to fear other men, which in a dictatorship they do. The freer the society, the more generous and benevolent men tend to be. That it's in free societies that people help each other. In enslaved societies, everyone is a potential spy, a potential danger to everyone else. But free men are generous men. They always have been.

Studs Terkel Yeah. She died about, uh, what--

Studs Terkel '82.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel So it's, uh, four years ago.

Barbara Branden Four years. Yes, yes.

Studs Terkel And--you knew her for a long time.

Barbara Branden Yes. I had not seen her in a lot of years. We had had a break. And, uh, I saw her for the first time again in 1981 and we spent a day together which--I'm very happy that happened, that we had a very warm, lovely day together.

Studs Terkel Though it's fair to say that the yuppies, if we use that overused phrase--and that's not all the young adult--but anyway, a good number of those, or the upscale kids--are Ayn Rand's children.

Barbara Branden To the extent that they're pro-business, uh, to the extent that they want to improve their lives and to do it all by rational means, yes. Yes, then I would say so. But with those qualifications.

Studs Terkel So there's the story of someone who has played a role in the way things are going

Barbara Branden Oh, yes, indeed she did.

Barbara Branden Yes.

Studs Terkel Did she ever talk about nuclear war, the dangers of that?

Barbara Branden No she didn't. She never thought the Soviet Union, without American help, would be too much of a danger. That, uh--she felt, again, that slaves are not productive people. And that if we stopped sending them our secrets and our materials and our ways of doing things, they would not be a danger to us, ultimately.

Studs Terkel Anything else you feel like adding to what we said?

Barbara Branden Just that--we've talked about her ideas, which of course is what Ayn Rand was all about. But she was a fascinating, enchanting, difficult, impossible, wonderful woman, who had--who had a life that stepped out of an Ayn Rand novel. That's really what hooked me on doing it, is that very fascinating life. [reading] "Ayn Rand was led to define two different ways of facing life. Two antagonists. Two types of man: The man of self-sufficient ego, of first-hand, independent judgment, and the spiritual parasite, the dependent who rejects the responsibility of judging. The man whose convictions, values, and purposes are the product of his own mind, and the parasite who is molded and directed by other men. The man who lives for his own sake, and the collectivist of the spirit who places others above self. The culture has changed since the '40s, in significant part, as a result of the works of Ayn Rand. Her ideas have spread, they have been heard, they have made a difference. The book and reality are working."